As the originator of the Gaia hypothesis, the British scientist helped shape the environmental movement in the 1970s. But Lovelock’s persistent support for nuclear power has also irritated many of his peers. He died on his 103rd birthday.

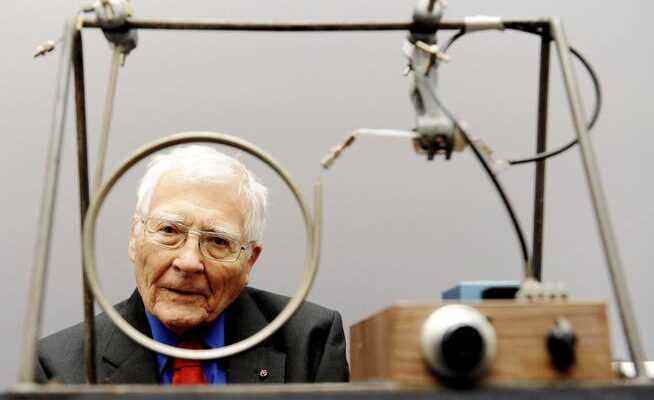

James Lovelock was also a great inventor. Here he is posing at the age of 94 with a self-made gas chromatograph.

By the age of a hundred, James Lovelock had become an optimist. In 2019, the British scientist and inventor published his last book, entitled «Novocene», which heralded a future that pleased the author. Sooner or later, Lovelock was convinced, super-intelligent machines would rule the earth. They would peacefully replace the deficient people, who would then be able to retire to a certain extent: henceforth, the fortunes of the planet would be in the hands – or rather in the programs – of superior intelligences.

This tech euphoria may come as a surprise, because Lovelock has become known for an idea that originally appealed more to esotericists than to scientists. Beginning in 1972, Lovelock developed the Gaia hypothesis with biologist Lynn Margulis. In essence, it states that the entire planet should be understood as an organism: as a self-regulating system in which life, atmosphere and matter interact and form a unit.

Lovelock has come a long way before he got to Gaia. Born in 1919 to a Quaker family, he holds degrees in medicine, chemistry and biophysics; he had worked for NASA and studied the atmosphere of Mars before delving deeply into our Earth.

Laws, not ghosts

It is no coincidence that the Gaia hypothesis emerged in the 1970s. Since the late 1960s, environmental issues had become an increasingly important issue. Up until then, problems such as water or air pollution had primarily been considered at the local level, but the perspective was now increasingly global. The first environmental conference of the United Nations in 1972 and the report published at the same time by the Club of Rome show that at that time there was an awareness of global problems.

An active environmental movement was also formed at this time. James Lovelock had a decisive influence on early environmental protection, and not only with the Gaia theory. In 1971, the Briton measured the CFC concentration in the atmosphere for the first time using a detector he had built himself – an important step towards discovering the ozone problem.

In the meantime, not only environmentalists but also spiritualists and New Age friends, who understood Gaia as a nature goddess, primordial mother or other moral authority, found Lovelock’s well-known theory appealing. Lovelock himself, of course, had nothing of the sort in mind. He broke away from his Quaker background early on, he did not follow any religion and designed the Gaia theory as a strictly scientific concept. He wasn’t interested in depicting the earth as a being with a soul, but rather as an overall system whose individual parts interlock according to the laws of natural science.

Alarmist forecasts

Accordingly, Lovelock advocated using technical means to repair the system where it had gone haywire. In 2007, for example, he proposed equipping the oceans with huge pumps to bring nutrient-rich water from the depths to the surface. This fertilization should lead to algal blooms, which are able to absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide.

Such ideas, which fall within the broad spectrum of geoengineering, have alienated some environmentalists who argued that corrective human intervention would always create new problems. But nothing has alienated Lovelock from the mainstream of the ecology movement quite like his staunch support for nuclear energy. When the environmental movement grew stronger in the 1970s, it naturally turned against nuclear power. Green Lovelock could never understand that, and the longer he defended it, the more resolutely he defended it.

In the expansion of nuclear power, he saw the only effective way to reduce CO with constantly high energy requirements2– Curb emissions. Lovelock considered the disposal of radioactive waste to be so unproblematic that in the 1990s he offered a British nuclear power plant operator to bury the nuclear waste in his own garden. The scientist stuck to this view after the Fukushima disaster: He, who had visited various repositories with his wife, would hardly be answering journalists’ questions at the age of 102 if the radiation were as dangerous as everyone wrongly believed, he told them January in an interview with the NZZ.

The increased promotion of nuclear power coincided with Lovelock’s growing concerns about the climate. In the 2000s, the independent scientist warned of dramatic scenarios in books and interviews, sometimes in a shrill tone: he predicted in 2006 that 80 percent of people would die by 2100. He later described his own predictions as alarmist. The concern may have remained, but by the end of his life, Lovelock had regained his composure.

James Lovelock was thus a highly original thinker in every respect: at a time when the climate was not causing much anxiety among the general public, the scientist banked on panic, and when many politicians were demonizing nuclear power, Lovelock hailed it as a green solution . Fear of climate change is widespread today, and the EU has elevated nuclear energy to green technology. Things are coming full circle, also in Lovelock’s life. He died on July 26, his 103rd birthday.