The meeting of the two great military leaders is still surrounded by myths. One thing is certain: it shapes the political order in Latin America to this day.

Meeting of Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín in the Ecuadorian port of Guayaquil on July 26, 1822 (illustration from 1844).

It was a historic meeting. Two hundred years ago, on July 26th and 27th, 1822, the two great fighters for independence who were in the process of liberating South America from Spanish colonization met in the Ecuadorian port of Guayaquil.

After ten years of campaigns, the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar had won independence from Venezuela and Colombia in 1821 and then turned his troops to Ecuador, whose capital Quito he brought under his control in May 1822.

Argentinian José de San Martín had liberated Chile and parts of Peru – after defeating the Spaniards in his homeland and crossing the Andes in a spectacular action. The debate between the two in Guayaquil decided how South America’s struggle for freedom should be brought to an end – and it still determines the political order of the region today. But first, let’s look back at the origins of the independence movement.

Discrimination by Madrid

In the 18th century, the dissatisfaction of Latin American-born white descendants of Spanish immigrants steadily increased. In the Spanish colonial system, they – the so-called Creoles or Criollos – were second-class citizens. Madrid distrusted them. Only whites born on the Spanish peninsula – therefore called Peninsulares – were allowed to hold high government and church offices in Latin America and trade with Europe.

After all, the most important economic activities in the region were reserved for the Creoles in the rigid hierarchy of the Spanish crown: As large landowners, they could cultivate crops and raise cattle and receive concessions for the exploitation of mines. Even further down the hierarchy was the vast majority of the population: the mestizos, the indigenous people and at the bottom the African slaves and their descendants.

The Creoles disliked the disadvantage compared to the Spanish-born Peninsulares, who – hardly arrived from Spain – were put in front of their noses. In addition, Madrid controlled trade with the colonies, to the detriment of the Creoles, which was officially only allowed to be transacted through Spain.

However, the time was not yet ripe for an uprising against Madrid. However, two factors accelerated the detachment. Towards the end of the 18th century, the revolutionary ideas of the European Enlightenment, the French Revolution and the independence movement in the USA also reached Latin America, where they formed the ideological foundation for an uprising against the Madre Patria, the mother country Spain.

The timing of the uprising against Madrid came after Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808 and replaced the king with his brother Joseph Bonaparte. The Creole elite skillfully exploited the resulting power vacuum, declaring independence from the mother country in important regional capitals in Latin America and forming revolutionary governments.

Collapse of the Spanish Viceroyalty

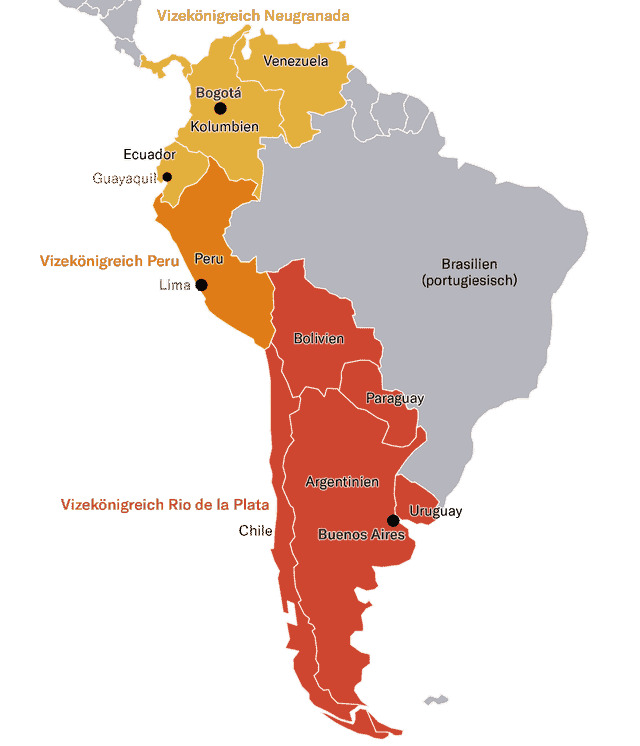

At that time, the Spanish part of South America was divided into three so-called vice-kingdoms. The economically most powerful was the viceroyalty of Peru with its capital Lima, which possessed great wealth in gold and silver mines.

The viceroyalty of New Granada, with its capital Bogotá, included what is now Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Panama. It was not until 1776 that the third viceroyalty, Río de la Plata, was formed, consisting of what is now Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Chile.

The independence movements emerged primarily in New Granada and in the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata, while rich Peru held the longest to the Spanish crown. First in Ecuador, the Creole elite declared independence from Spain in 1809. In Colombia, Venezuela and Argentina, the fall of the Spanish governments followed a year later. The uprisings triggered years of bloody wars of independence with the troops loyal to Spain, until Bolívar and San Martín finally prevailed.

Simón Bolívar – a wealthy Creole from Venezuela

Simón Bolívar was born in Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, in 1783 into an aristocratic Creole family. Thanks to great wealth in land, slaves and mines, the Bolívars were among the wealthiest Creole families in Spanish America.

Simón enjoyed lessons from Caracas intellectuals, who introduced him to the ideas of the Enlightenment and the French and American Revolutions. Between 1799 and 1807 he lived mainly in Europe and the USA, where he became acquainted with the revolutionary movements.

Bolívar developed a deep hatred for the Spaniards, who he believed were oppressing the Creoles. He studiously overlooked the fact that the Creoles also enjoyed a privileged status based on the oppression of the large majority of the population of mestizos, indigenous people and blacks.

His vision of liberation focused on the Creole upper class. His political actions were strongly influenced by the fear that the poor majority of the population would rebel against the Creoles and enforce their own liberation. As a successor to the Spanish colonial empire, he dreamed of a contiguous state from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego, comparable to the United States in North America.

When the Creoles seized power in Caracas in 1810, Bolívar was one of the driving forces. Twice the royalists managed to recapture the Venezuelan capital Caracas. In 1814, Bolivar fled to Jamaica and Haiti. At the end of 1816 he founded a base in the Orinoco Valley in the east of the country, since he felt it was hopeless to conquer Venezuela from the well-fortified coast in the west.

His plan was to roll up the field from behind, first liberating Colombia entirely and then taking control of Venezuela from there. With a force of 2,500 men, he moved from western Venezuela across the Colombian Andes and decisively defeated the Spaniards at Boyacá in 1819. Then he moved to Bogotá. After another fateful victory in July 1821 at Carabobo, Venezuela was finally liberated. Bolívar then sent his subordinate Antonio José de Sucre by sea to Ecuador. Even before Bolívar arrived, he defeated the Spaniards there in May 1822.

San Martín – born in Argentina, raised in Spain

Unlike Bolívar, San Martín was the son of Peninsulares. His parents came to Argentina in 1774, where his father took over the post of regional governor. Four years later San Martín was born there, but when the boy was six the family moved back to Spain.

At the age of eleven, San Martín joined the Spanish Navy as a cadet and later fought in North Africa and Portugal, among other places. During this time he came into contact with the ideas of the Spanish Enlightenment.

In 1808 he fought on the Spanish side against the French invasion. After Napoleon’s victory, he moved to London, where he mobilized supporters for the independence of Spanish Latin America.

In 1812 he returned to Buenos Aires and joined the independence fighters. Two years later he was appointed Commander-in-Chief by the revolutionary government in Buenos Aires. After defeating the Spanish in Argentina, he raised an Andean army with the aim of liberating Chile and then Peru.

In 1817 he crossed the Andes at the 4476 meter high Paso de Los Patos in a daring forced march with the main force of around 4000 fighters and 1200 auxiliary troops. The rest of the force moved over the Uspallata Pass further south. A third of his crew died during the 21-day expedition. Nevertheless, he subsequently managed to decisively defeat the royalists in the battles of Chacabuco (1817) and Maipú (1818) and win independence from Chile.

As a result, San Martín raised a fleet and sailed to Peru with eighteen ships. In June 1821 he was able to take the Peruvian capital Lima. The Spanish troops retreated to the Andes. But San Martín lacked the strength to liberate all of Peru. He therefore hoped for reinforcements from Bolívar, who had meanwhile reached the Ecuadorian port of Guayaquil, where the historic meeting took place.

Summit meeting in private

The two-day meeting took place in private. Therefore little is known about it. However, it was of greater symbolic importance than any other event during the wars of independence. Two items were central to the agenda.

The first concerned the question of how the liberation of the areas of Peru and Bolivia still under Spanish control should be carried out. San Martín proposed raising a joint army. But Bolívar refused because he did not want to share the glory of the final liberation of South America with San Martín.

The two leaders were also unable to agree on the second question, how liberated Peru should one day be governed. San Martín favored a constitutional monarchy, believing it was the only way to bring order to the chaos created by the Revolutionary Wars. He believed that the Peruvians loyal to the king were not yet ready for a republic.

Externally, Bolívar advocated a republican form of government, but actually he had in mind an oligarchy of the wealthy Creoles. On the second day, San Martín left Guayaquil disappointed. Unable to assert himself against Bolívar, he returned to Buenos Aires, where he abruptly withdrew from public life.

Formative role of Bolívar

Bolívar, on the other hand, now devoted himself to the conquest of all of Peru, which was completed in December 1824. Only four months later, the Spaniards also capitulated in Bolivia, which means that the Spanish colonial empire in South America had fallen completely.

Bolívar was at the height of his power. In addition to his presidency of Greater Colombia, the former viceroyalty of New Granada, Peru and Bolivia now also made him head of state. But his vision of a continental confederation from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego failed once and for all with the dispute with San Martín.

Not only the southern part conquered by San Martín was broken away. The political order in the northern part of South America also dissolved in the following years: Venezuela and Ecuador separated from Greater Colombia. In May 1830, Bolívar also lost control of Colombia and retired from all offices. But his legacy still shapes the region today: not only in the fragmentation of Latin America into numerous states, but also in the tradition of strong, centralized presidential regimes, which he considered necessary to hold the countries together.

An end in oblivion

It is an irony of fate that the two great fighters for independence disappeared into insignificance in their twilight years. Bolívar, who had sacrificed his fortune to the war chest, was destitute after his resignation and had to sell his last belongings to survive. He tried to go into exile in Europe, but died of consumption on December 17, 1830 on the way to the coast.

On his return to Buenos Aires from Guayaquil, San Martín realized that he had been forgotten in his homeland. In 1823 he emigrated to Europe with his daughter and died in 1850 in Paris. It was only decades later that the two independence fighters gradually attained their heroic status in South America, which has lasted to this day.