Saturday May 22, 2021

Abundance here, lack there

The battle for medical oxygen

By Charlotte Raskopf

There is a dramatic lack of oxygen in India. The tense situation in the pandemic is moving an industry that otherwise operates in the background. How big is the market, what is the importance of the air business and why does Germany have so much and India so little?

In India a real battle has broken out over rare bottles of medical oxygen. The corona numbers skyrocketed, the intensive care units filled – and soon there was no longer enough medical oxygen for all patients. There is a dramatic lack of oxygen in India. A whole black market has established itself around the life-saving bottles, on which a multiple of the usual price is demanded. But if you get the chance, you usually pay without batting an eyelid. There is simply no alternative.

Police officers guard containers of liquid medical oxygen (LMO) after an oxygen express arrives at a Bangalore train station.

(Photo: imago images / Xinhua)

The tense situation in India has brought an industry to the fore that otherwise tends to operate in the background: oxygen production. Oxygen is used in hospitals, but also in various branches of industry. “It is also often used as bottled oxygen in welding and flame cutting,” says Stephen B. Harrison, managing director at the management consultancy sbh4 and an expert in industrial gases. The substance is used on a large scale in heavy industry such as steel production or in refineries.

Germany is particularly well positioned here. “In countries with high industrial activity, the market for oxygen is large,” says Harrison. Wherever steel production and refineries are widespread, a lot of oxygen is needed – and also produced. The production of industrial gases generates an annual turnover of 2.6 billion euros in Germany.

Highly specialized manufacturing

Oxygen is produced in highly specialized factories that use a lot of electricity. First, the air is sucked in and then processed, says Harrison. “In this process, the gaseous air becomes liquid air and it is then split up into oxygen, nitrogen and argon,” he says. Each of the gases is then used for different purposes. The oxygen is either transported in pipelines to large customers in the vicinity, such as steelworks and oil refineries, or it is delivered in liquid form by trucks. Gaseous oxygen is also bottled for hospitals. Harrison explains that hospitals can also use special equipment to produce oxygen themselves by purifying the air into medical oxygen.

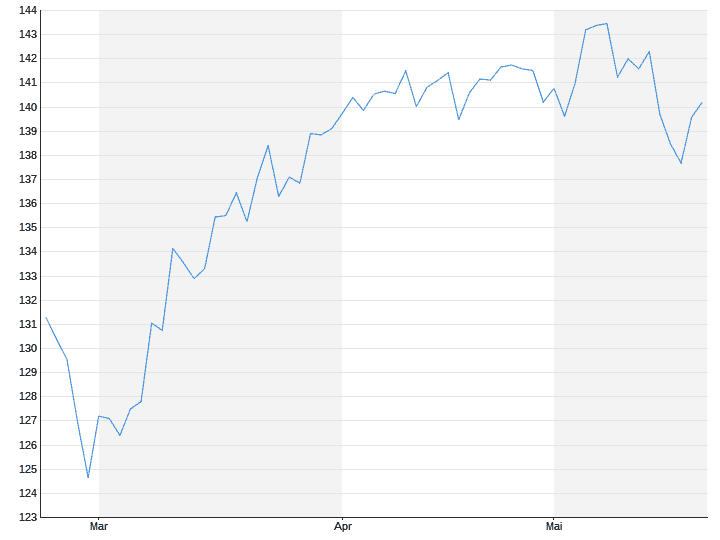

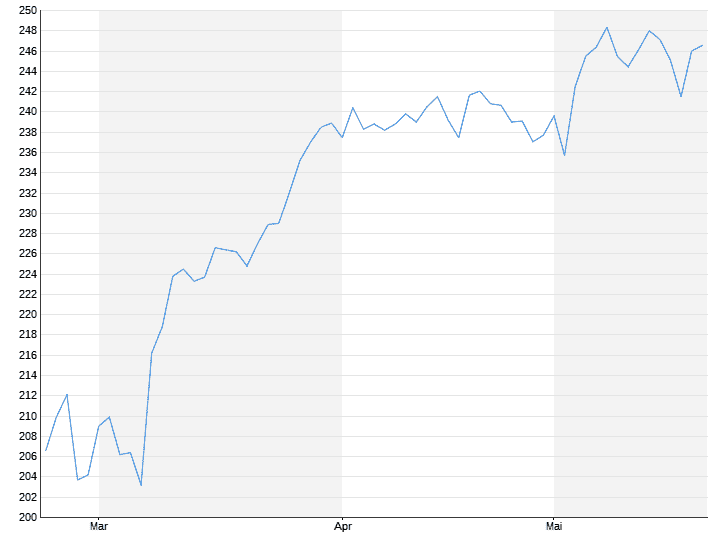

The world leaders in the oxygen market include Air Liquide and Linde. According to its own statements, the French company Air Liquide is the “world market leader in gases, technologies and services for industry and healthcare”. The company employs more than 60,000 people in almost 80 countries. The group achieved sales of around 20.5 billion euros last year. Linde merged with US competitor Praxair in 2018, making it the world’s largest supplier of industrial gases. Linde generated sales of US $ 27.2 billion last year.

At Linde, the corona pandemic and the associated increase in oxygen demand are already noticeable in the business figures: sales in the health division, which also includes medical oxygen, increased by ten percent in the first quarter.

Favorable conditions in Germany

In Germany, it is not a problem to meet the increasing demand for oxygen, says Harrison – despite the high demands on medical oxygen. It must be particularly pure and is considered a medicinal product. “We make enough oxygen for industry. If we just produce a little more oxygen in the factories that are designed for this purpose and turn it into medical oxygen, we can meet the demands of hospitals,” he says.

It is different in countries like India or Brazil. Such countries are less industrialized. Accordingly, less oxygen would be produced there per inhabitant. But the lower amount of available oxygen is not the only problem. The other is logistics, because that is also much more difficult in India: There are very different geographical conditions and different legal requirements for transport in each state, says Harrison. But there is also a lot of creativity, for example the government has allowed transport methods that were previously forbidden.

Harrison hopes the demand for medical oxygen will return to normal soon. “In the long run, growth in developed countries like Germany will primarily come from new applications such as the production of blue hydrogen as a clean energy source,” he says. In developing countries like India, various factors are decisive for future growth in oxygen demand: population growth, increased industrial activities and greater access to medical care.

This article first appeared at Capital.de.

.