Allotment gardens have always been subject to major changes. In Basel, they should now be better integrated into the districts. The tenants see their privacy threatened.

Fear of losing privacy: when strangers suddenly look over the fence into the garden.

If there is a paradise on this Monday morning, then it is between Basel and Riehen. To be more precise: in the Spitalmatten area, one of the largest leisure garden areas in the canton of Basel-Stadt. Warm late summer light shines at ten o’clock in the morning and there is a stillness as if the seriousness of life were light years away. The long, hot summer and the industriousness of the hobby gardeners (mostly the gardeners) have provided for a splendor of flowers. All around, fruits and vegetables are being harvested, raspberries, figs, beans, tomatoes. From a distance, only the rattling tram is reminiscent of the hustle and bustle of the city, but who cares?

Peter Wirz is sitting under the canopy of his garden shed, in front of him a coke and a glorious day. Nevertheless, the pensioner is dissatisfied. His idyll is threatened by a small but nasty revision of the law that Basel is about to vote on: In the future, the allotment garden areas are to be developed with individual walking and cycling paths and thus made accessible to the public.

This “passing through”, as it is called in cheerless administrative language, should bring added value for the population in the city heated up by climate change. From Peter Wirz’s point of view, it means the end of privacy in a piece of home.

Schreber wanted to raise children like plants

In many cities, leisure or family gardens are in the best locations and as such do not fit in well with the trend towards densification. Investors are looking for space for apartments and offices, but at the same time green spaces are becoming more important in view of climate change and the warming of cities.

Thanks to organic and urban gardening, allotment gardens are developing from being the epitome of Bünzlitism to becoming a popular place for young urbanists to realize themselves. The tenants are still tending to be overaged. But the waiting lists are getting longer. For many city dwellers, the gardens are an inexpensive retreat in the countryside and represent a piece of individuality. Every city government knows that if they target the garden areas, things get complicated.

The man to whom the gardens owe their original name had little to do with relaxation and free development. In the 19th century, the pediatrician Daniel Moritz Gottlob Schreber propagated a repressive educational system according to which children, like plants, were to be brought into shape through strict rearing. He developed martial methods to make decent people out of the city youth.

Although he did not personally invent the allotment garden, public health and physical exercise were at the very beginning of allotment gardening. Poor nutrition and precarious living conditions had a disastrous effect on health during industrialization, and there was also a fear that the youth would be neglected. Significantly, in 1909 in Basel, the “Women’s Association for the Raising of Morality” became aware of the allotment garden movement.

Gardening becomes a civic duty

At the turn of the century, allotment garden initiatives emerged in many European cities, which ultimately became an integral part of social policy. The factory workers depended on subsistence and grew potatoes and vegetables in their gardens.

During the First World War, the supply situation deteriorated dramatically, as can be seen from the founding minutes of the Central Association of Basel Family Gardeners’ Associations from 1918: Thefts in the gardens increased, which is why the tenants joined forces. It quickly turned out that just guarding the gardens was not enough. The distribution of land is generally unfair, for which “all sorts of examples were listed” at the first meeting.

In the Second World War, the supply situation was even worse, gardening even became a civic duty. As part of the cultivation battle, the Basel government council launched the “Us own Bode” campaign. Tenants were obliged to grow potatoes, using the same arguments that count again today with the emergence of the ecological footprint: milk and meat from 40 ares of land fed only one person, the authorities calculated in advertisements – potatoes on the same area but six people. Food was so scarce and expensive that allotment gardens once again became vital for many people. Conversely, tenants had to reckon with the confiscation of the garden if productivity left something to be desired.

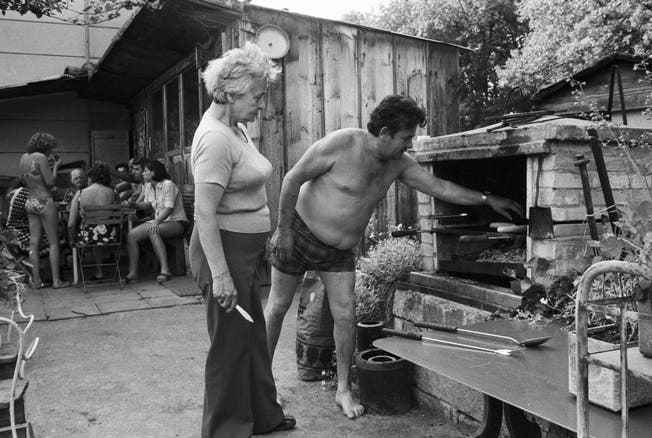

Only with the economic boom after the Second World War did self-sufficiency lose its importance. Gardening developed into a leisure activity, vegetable beds were reduced, and lawns, ornamental shrubs and barbecue areas were used instead. At the same time, demand fell and many areas disappeared. The cities used them as land reserves or overbuilt them.

Allotment garden idyll in the Zurich area, photographed in August 1978. Gardening is often associated with half a family life and many memories.

In Basel-Stadt, for example, there are only half as many allotment gardens today as there were in 1945. But even when the economy was booming, the parceled green spaces reflected the sociological realities: from 1960 immigration made itself felt, and the Basel allotment garden regulations were published in Italian for the first time. More and more, the gardens developed into a place of relaxation for city dwellers.

Littering, theft, arson

Peter Wirz is also not dependent on his garden on the Spitalmatten. The family decided to lease more than thirty years ago at the request of Wirz’ wife, who loves gardening more than anything. So he has his peace and quiet at home, Wirz jokes. For him, too, half a family life and many memories are connected with gardening. When it’s warmer, Peter Wirz and his wife spend a few hours here almost every day. Garden maintenance takes time, but at the same time the plot is a piece of luxury at an affordable price: a tenant pays a few hundred francs a year for an area of around 200 square meters.

Wirz is all the more horrified at the thought of people suddenly strolling through the gardens. “If staying in the country is so important, you can take a tenant course or go for a walk in the ‘Lange Erlen’,” he grumbles and is annoyed at the “bloated building department” that puts such half-baked ideas into the world. He fears an increase in littering, vandalism and theft. Only a few years ago, eleven houses burned down on the site.

Wirz is also worried about the women who would be exposed to strangers’ looks in the future if they were lying in the sun in a bikini. The building department assures that only a few paths are planned, which are also fenced off. Often the main concern is that the garden areas that are closed today no longer form a barrier between the quarters. But that doesn’t reassure the gardeners. For many, the plans are an intrusion into their personal lives.

Much of the Basel garden debate is reminiscent of the resistance of lake residents to public waterfront promenades. In Basel, the dispute even leads to a unique alliance between the left-wing extremist Basta and the SVP, which fights “against the destruction of the green oases”. In the meantime, the FDP base has also put its party on an opposition course. Right in the middle is Peter Wirz, who is present on almost all channels as the face of family gardeners.

A few days before the vote, it seems more open than ever whether the tentative opening of family gardens will succeed. Already ten years ago, the garden lobbyists prevailed with the help of a popular initiative and enforced a law in Basel-Stadt, according to which 8o percent of the existing allotment gardens have to be maintained in the future or replaced if they are abolished.

The new longing for rural life

It is no coincidence that the dispute over the future of family gardens is being fought so fiercely in Basel-Stadt. Nowhere are the canton borders so close and the conditions so cramped. But at the same time the dispute makes it clear where the journey is going, probably soon to other cities as well. With the urban longing for rural life and with every hot summer, interest in green open spaces increases. Wirz himself observes that more and more people are appearing among the tenants who are neither connected to the floe nor have a green thumb.

The family garden scene is still reacting skeptically to the attempt to better integrate the areas into the quarters. But if I am not mistaken, the new walkways through the Basel Gardens are just the beginning: a hundred years after their spread, allotment gardens are given a new urban planning and sociological function – and more weight.