Calves that are suckled by their mother: This is rare on conventional dairy farms. Why is that?

Strange under what circumstances people start to think about animal husbandry. Sometimes breastfeeding mothers call Martina Knoepfel at the Brüederhof and ask: How are you doing with the calves? How are they fed? They suckled from their mother, says Knoepfel then.

Sounds logical. Sounds natural. After all, the cow is a mammal and produces milk for her young. But it is also a farm animal, the most important in Switzerland, and as such the cow produces milk almost exclusively for humans. Calves being suckled by their mothers: that hardly ever happens in this country, not even in most organic farms. Most calves are separated from their mothers shortly after birth so that all of their milk can be used for milk processing. Animal rights activists criticize this as torture.

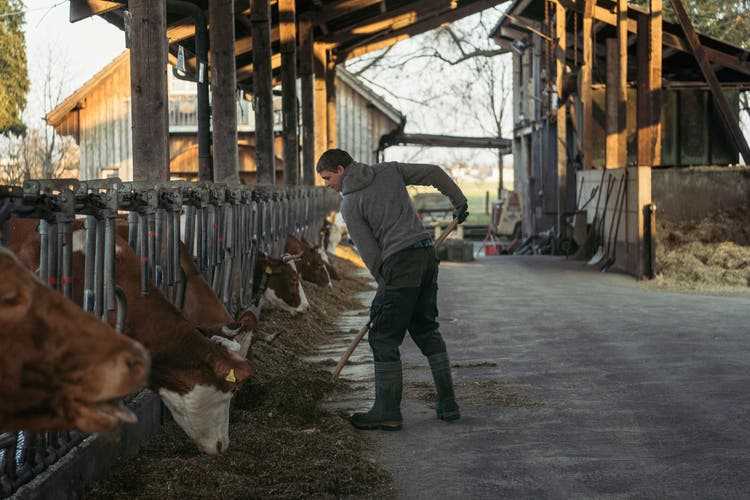

In this environment, the Brüederhof in Dällikon in the Dielsdorf district, on the border to Aargau, is exotic among Swiss milk producers. On an afternoon in March, Martina Knoepfel walks past the large pen with around 40 cows, all of which have horns, to a box. Inside is the cow named Rotonda, a mighty animal that watches visitors with wide eyes. Rotonda gave birth to a calf a few days ago. It’s lying in the straw in a corner, it looks tiny, but it already weighs 50 kilos.

The cows on the Brüederhof have horns, so they need more walking space.

This calf is only a few days old.

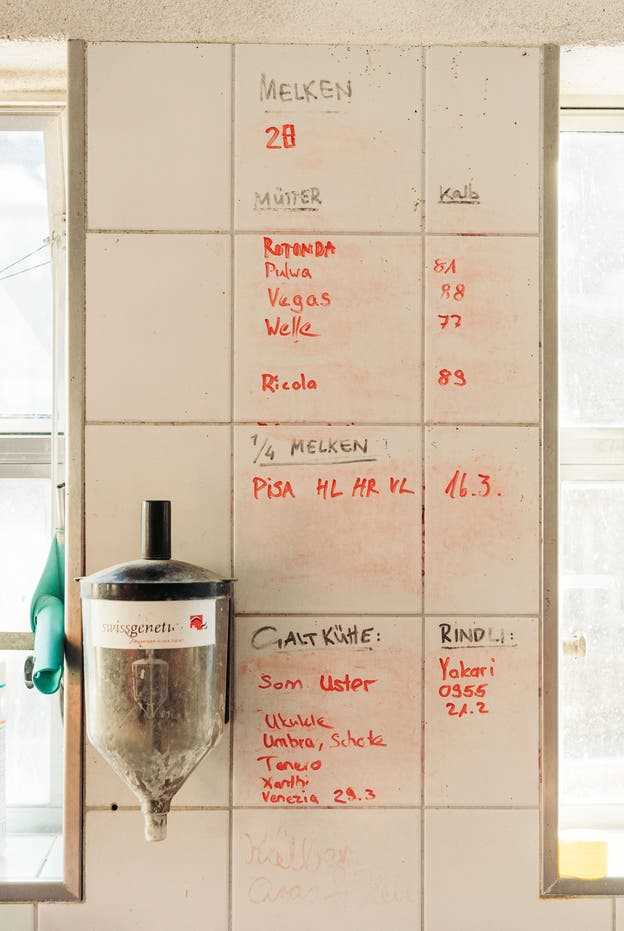

It doesn’t have a name yet, it’s supposed to start with a B, like all the calves this year. Maybe boomerang? That would suit Rotonda. At the Brüederhof, all calves have a name that reminds them of their mother. The calf from Ricola is called Bonbon, that from Vegas was christened Brooklyn.

The still unnamed calf had its mother all to herself for the first few days of its life. These first days, says Knoepfel, are crucial for his development. Because calves do not have an active immune system immediately after birth. It is only built up when the young animals drink the mother’s colostrum. This is the name of the milk that a cow produces immediately after giving birth to her calf. It contains antibodies that make the calf resistant to germs. Knoepfel describes it like this: “The calf gets the milk that is precisely tailored to its gene pool.”

The milk comes from the bucket instead of the udder

The importance of this milk booster for calf health is undisputed among experts. In conventional animal husbandry, however, it is assumed that the calf should be separated from the mother because it could contaminate the milk when suckling. It is then kept separate from the herd in a fenced calf igloo and fed milk from buckets with teats modeled after a teat. It only sees its peers from afar.

Left: the cow Rotonda, which gave birth to a calf a few days ago. Right: Some of the milk is sold directly from the farm.

The igloos have many advantages for the calf, the weekly newspaper “Zürcher Bauer” wrote in an article in 2019: “Due to the spatial separation, the infection pressure is lower.” And: “The environmental stimuli promote vitality and health, fresh air and light are sufficiently available, provided the igloos are set up outdoors.”

When she sees calves that are completely isolated, it hurts her, says Knoepfel. From her point of view, there is another reason besides animal welfare why it makes sense not to separate mother and calf immediately. “We have a lot less work because we don’t have to feed the calves.” And the animals are even healthier. “They are practically never sick, we hardly have to use antibiotics.”

Mother-bound calf rearing has been practiced at the Brüederhof for 25 years. At that time, Simon Knoepfel’s father, Kaspar Günthardt, was one of the pioneers in Switzerland. And with this form of attitude he was moving in a legal gray area. The ordinance on foodstuffs of animal origin stipulated that farmers must sell all of the cow’s “milk”. The Schaffhausen SP National Councilor Martina Munz suggested in a motion to adapt the law; it was accepted in spring 2021.

“It used to be said that the quality of the milk suffered if you let the calves suckle,” says Knoepfel. The Research Institute for Organic Farming carried out an investigation, including milk samples from the Brüederhof. “The result showed that the milk is perfect.”

The milk that has been milked ends up in a large cauldron.

A cow on the Brüederhof produces around 6,000 kilograms of milk.

Swissmilk media spokesman Reto Burkhardt says it was primarily the legal uncertainty that kept farmers from switching to mother-bonded calf rearing. They feared that they would not find buyers for the milk.

In principle, there is nothing to be said against this form of husbandry, says Burkhardt. However, it is not suitable for every farm: “It needs an infrastructure in which the calf can drink from its mother in peace.” Rebuilding the barn accordingly could entail high investments.

Pregnant for life

Of course, even a farm that wants to take the natural behavior of the cow into account as much as possible has its limits with its love of animals. Because a cow does not automatically give milk, but only when she has given birth to a calf. That is why cows on dairy farms are fertilized as quickly as possible after the birth of their calf. Without this principle there would be no dairy farming. The cow is practically its own high-performance farm.

Almost all cows are pregnant at the Brüederhof. To ensure that the milk supply remains constant, the young animals are born over the course of the year. And the cows with their calves are also milked. Rotonda will return to the pen for a few hours over the next few days and eat with the other cows.

Left: A list shows which cows are suckling calves. Right: Simon and Martina Knoepfel run the Brüederhof.

This period of time is gradually increased until the young animal finally joins the other calves in an area separated from the pen. “If you wean the calves like this, the pain of separation is not so great,” says Knoepfel. Twice a day, before milking time, the calves are let into their mothers’ pen to suckle.

Around 6,000 kilograms of milk are produced per cow on the Knoepfel family farm every year; Across Switzerland, the average is 7,000 kilograms per cow. Although the Brüederhof keeps slightly more animals than an average farm with around 40 cows, it produces less milk. Knoepfel explains this difference with the fact that the cows do not receive concentrated feed that can increase milk yield. “We don’t want to get the maximum out of a cow.”

Throughout Switzerland, the path points in a different direction. Today there are only half as many milk producers as twenty years ago, and at the same time the amount of milk marketed per farm has doubled.

How much does the consumer want to pay?

The Knoepfel family sells some of the dairy products in their own farm shop. A liter of milk costs two francs, just a little more than the organic milk from the wholesaler. The largest buyer is the wholesaler Pico Lebensmittel AG, which supplies the online shop Farmy, among others. The products are sold under the “Bio-Horn-Milch” label by KAG Freiland. The Brüederhof does not declare it as milk from mother-calf husbandry. “Too many labels confuse consumers,” says Knoepfel.

The “milk from happy calves” is a niche product – and should remain one for the time being. Reto Burkhardt from Swissmilk says that society and farmers are giving animal welfare more and more weight. How many farmers switch to mother-tied calf rearing in the long term depends above all on one aspect: how much the customer is willing to pay for a liter of milk. The market speaks a clear language: Although the proportion of organic milk in total milk production is steadily increasing, it is only eight percent. Most consumers therefore continue to buy milk from conventional production.

Almost all cows are pregnant at the Brüederhof.

A rare sight on farms: a calf suckling from its mother.

The “happy calf” will not be able to get rid of the quotation marks for the time being, because most animals are given a short life. The nameless calf on the Brüederhof is a male and therefore has no place in milk production. At the age of three weeks it will go to a fattening farm and later be slaughtered. The female rearing young animals are allowed to suckle from their mother for around three months until they are placed in a separate stable. At this age, they no longer need breast milk.

In the group of calves on the farm, however, there is a male calf that has passed the three-week mark. Ayu is now almost five months old. His mother Pulwa is particularly caring. She stands right next to the calf barn and waits impatiently. Their internal clock says: soon it will be time for the calves to be left with their mothers.

Ayu is one of the calves whose meat is sold straight from the farm after slaughter. That is why he is granted more time with his mother. Ayu drinks around ten liters every day at Pulwa’s, which is around half of the milk she produces every day. “Some farmers will say: It makes no sense to give so much milk to a calf,” says Knoepfel. “But it’s worth it for the health of the calves. And that’s why it’s true for us.”