Near the village of Normétal in western Quebec where thousands of hectares of forests burned, September 22, 2023 (AFP/Mathiew LEISER)

“Never before seen”, “exceptional in scale, duration”, “huge long-term consequences”: when scientists look at the figures to take stock of the fire season in Canada, they struggle to find the right superlatives.

“It’s simple: we have shattered all the records on a Canadian scale,” said a shaken Yan Boulanger, a researcher for the Canadian Ministry of Natural Resources.

There have never been so many areas burned (18 million hectares, 6,400 fires), people evacuated (more than 200,000), provinces affected, megafires…

“It’s an impressive wake-up call because we didn’t necessarily expect it so quickly,” this forest fire specialist told AFP.

In Quebec, a province very hard hit and less accustomed than the West to very large-scale infernos, the shock wave was immense, particularly in the remote region of Abitibi-Témiscamingue, where the forestry industry is crucial.

No more leaves on the branches, blackened trunks and charred roots: in one of its black spruce forests, the queens of the boreal forest, only a few tufts of moss resisted the onslaught of the flames in June.

“There is little chance that this forest will be able to regenerate, the trees are too young to have had time to form cones which ensure the next generation,” estimates Maxence Martin, professor of forest ecology at the University of Quebec in Abitibi-Témiscamingue.

– A third of forest lost –

Record for burned areas in Canada (AFP/Jonathan WALTER, Valentina BRESCHI)

Faced with this alarming assessment and “if we continue on the current trend, by 2100, it is probably a third of the boreal forest that we will have lost in Quebec”, adds this enthusiast, slaloming among the young people green shoots that appear on the burned ground.

Yet this ring of greenery, the largest expanse of wilderness in the world, which encircles the Arctic – from Canada through Alaska, Siberia and northern Europe – is vital for the future of the planet.

Fires there are fueled by drier and hotter conditions caused by climate change. And by releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, these fires in turn contribute to global warming, in a vicious circle.

Another particularity of this northern forest: it releases 10 to 20 times more carbon per unit of burned area than other ecosystems.

Burnt trees near Lebel-sur-Quévillon, a small Quebec town evacuated twice during the summer, September 21, 2023 (AFP/Marion THIBAUT)

With the fires, Canadian emissions reached unprecedented levels this year (473 megatons of carbon), more than three times higher than the previous record, according to data from the European Copernicus observatory.

And in the boreal forest, due to the thickness of the humus on the ground, fires can continue to burn underground for months.

“As we explained to people that the fires would only really be extinguished with snow, everyone dreams of seeing winter arrive,” smiles Guy Lafrenière, mayor of Lebel-sur-Quévillon, a Quebec commune of 2,000 inhabitants which had to evacuate twice in June.

The forestry industry is working to collect as much wood as possible burned during the summer before it is too late, here in Lebel-sur-Quévillon in Quebec, September 21, 2023 (AFP/Mathiew LEISER)

The homes were saved from the flames thanks in particular to a lake which stopped the advance of the fire. But the entire summer was disrupted, no child finished their school year and hundreds of small chalets built in the forest were destroyed.

Today, the city is surrounded by fire trenches, created to counter the advance of the walls of flames, by removing the very flammable conifers.

“The machines cut down the trees and we had a helicopter to water them at the same time so that they did not catch fire,” recalls the mayor, who now wants to see the city surrounded by deciduous trees, much less flammable, so that They serve as a barrier.

– Overwhelmed –

For months, a large part of Canada, including the Far North, has been affected by an acute drought. It often took just one day of lightning to trigger hundreds of fires at the same time, overwhelming firefighters and authorities and overwhelming residents.

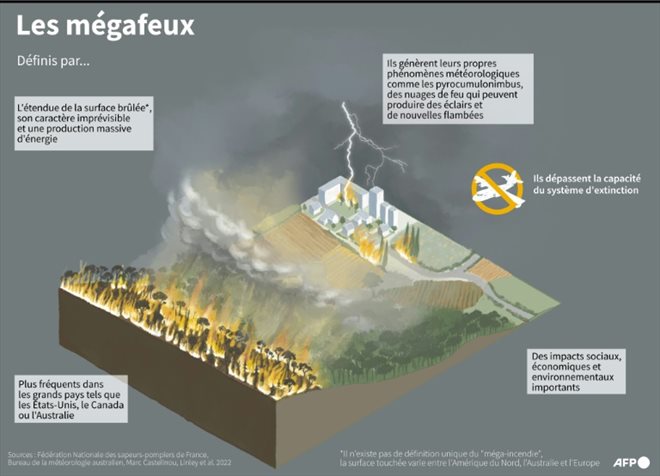

Megafires (AFP/Sophie RAMIS, Helena GISBERT SANCHEZ)

“People had five minutes to get out of their homes and leave. It was intense and stressful, especially since there was a lot of smoke and the flames were very close,” says Doris Nolet, head of the volunteer fire department of Normétal, another village. Quebecers evacuated.

The latter, who supervises a team of 20 people, was very afraid for her “guys”. “It was the first time that we were confronted with forest fires. We are trained for house and car fires,” continues this little woman with piercing blue eyes.

This year, almost all Canadians have been affected by this fire season, either directly or because they have breathed smoke from the fires that have traveled thousands of kilometers, also repeatedly polluting the air in part of the northern United States.

“We need to think deeply.” It’s not Europe here, we don’t have the means to fight all the fires, they are too big, too inaccessible so we have to be proactive,” explains Marc-André Parisien.

For this researcher specializing in fire risk management, these megafires have not finished haunting Canadians.

© 2023 AFP

Did you like this article ? Share it with your friends using the buttons below.