Tourists visit a farm whose plantations offset the carbon footprint of its visitors, in Heredia (Costa Rica) on October 28, 2020 (AFP/Archives/Ezequiel BECERRA)

Planting trees or protecting or even developing a tropical forest: companies are ready to do anything to offset their CO2 emissions and claim to be “carbon neutral”. But recent scandals show that the world of carbon credits remains a Wild West opening up many possibilities for greenwashing.

Among the emblematic cases: Walt Disney and the bank JP Morgan, among others, would have bought carbon credits resulting from projects of protection of forests whereas these last were not threatened.

A company in charge of exploiting 600,000 hectares (half of Ile-de-France) in the United States would have been paid 53 million dollars in two years for credits which did not really change the way forests were exploited.

Carbon stored by forests (AFP/Sabrina BLANCHARD)

In both cases, the carbon credits sold by operators gave companies the illusion that they were protecting trees, which through photosynthesis absorb carbon, when they were not in danger of being felled. No additional carbon has been absorbed, yet large companies will deduct them from their own carbon balance sheet, to offset the emissions resulting from their activity.

At the One Forest Summit, co-chaired by France and Gabon on March 1 and 2 in Libreville, participants will reflect on improving these financial instruments.

Carbon credits are already massively used and according to different estimates, the corresponding number of tonnes of CO2 (one credit = one tonne) could increase tenfold by 2030, to approximately 2 billion tonnes.

“The risky side of this market is that it is not self-regulating,” César Dugast, of the firm Carbone 4, told AFP. “Everyone has an interest in maximizing the quantity of carbon credits. of the project because it will thus be able to dilute the total cost in a maximum of credits. And the buyer who wants low-cost credits. And the certifiers have an interest in seeing the number of projects increase.”

A young acacia tree grows in the village of Ibi (Democratic Republic of Congo) on October 11, 2011. Acacia trees are planted with cassava in an attempt to trap carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (AFP/Archives/Gwenn DUBOURTHOUMIEU)

In mid-January, the Guardian, Die Zeit and an NGO revealed that more than 90% of the carbon credits certified by Verra, the undisputed leader of certifiers, for projects supervised by the UN to avoid deforestation (REDD+) were probably “phantom credits” that do not represent a “real reduction” in greenhouse gases.

Conclusions rejected by the general manager of Verra, David Antonioli. He asserts that “REDD+ projects are not abstract concepts: they bring real benefits on the ground”.

– Carbon credits in debate –

In the aftermath, the price per ton of carbon for nature protection credits fell, explains Paula Vanlaningham, carbon manager at S&P Global.

Elimination of CO2: reservoirs of the carbon cycle (AFP/Sabrina BLANCHARD)

Beyond doubts about the methodology of REDD+ projects, the revelations opened up a debate on all carbon credits. “Are they the right financial vehicles to lead to a fairer transition? Yes and no,” she replied to AFP.

Several independent rating agencies then defended their methodologies, advancing the crucial need for financing for the projects.

“First, we look at the additionality of the project: would it have existed without the carbon financing? Then we look at how the trajectory was established, we establish a hypothesis of what would have happened without the project”, argues Donna Lee, co-founder of the agency Calyx Global.

The central problem with projects that are supposed to prevent deforestation is that it is, by definition, impossible to prove that deforestation would have occurred without the funding.

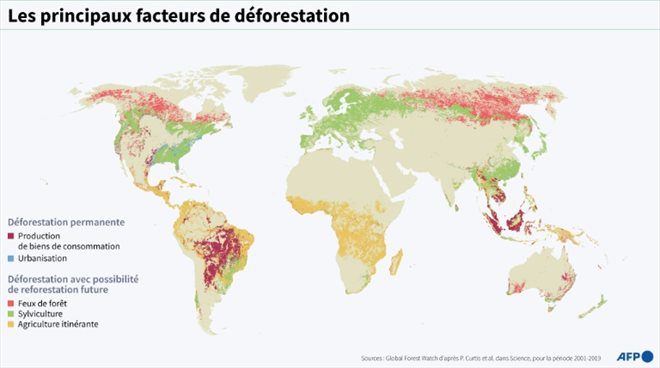

The main factors of deforestation (AFP/Sabrina BLANCHARD)

“But we can look at deforestation scenarios in the region (…), scientific studies show that certain factors, such as proximity to a road, populations or distance from the edge of the forest are correlated with deforestation”, defends Donna Lee to AFP, while admitting that improvements are necessary.

But above all, the companies that then buy these credits should be “more transparent”, she pleads, clearly indicating where the credits come from and how they manage to reduce their own emissions.

Because this is indeed the key to achieving carbon neutrality in 2050 as targeted by the Paris agreement.

“The word compensation must be abandoned in favor of a logic of contributions”, concludes César Dugast. In short: yes, companies can finance forests, but not as a privilege allowing them not to reduce their own emissions.

© 2023 AFP

Did you like this article ? Share it with your friends with the buttons below.