The criminal has relentlessly exposed the failings of the judicial authorities. But measuring the system against him alone would be wrong.

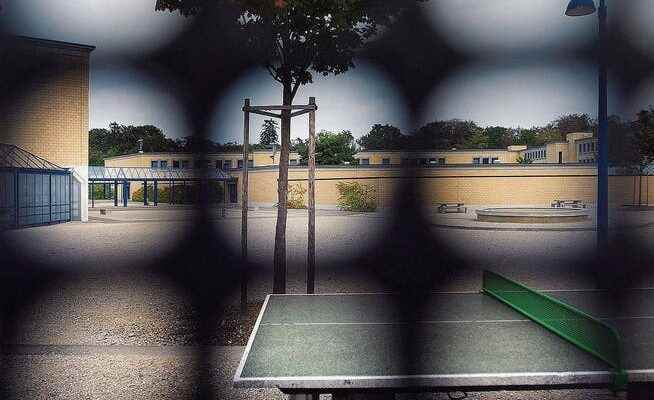

The Pöschwies correctional facility: Brian was held here in solitary confinement for over three years.

Brian polarizes more violently than any other Swiss prisoner. For some, he is a victim of the judiciary and should be released, for others it’s the other way around: For them, the 27-year-old is an incorrigible and dangerous violent criminal who should be behind bars – preferably forever. There doesn’t seem to be a middle ground.

The drama about the criminal is a lesson in how the fight between inmates and the judiciary can escalate. It is a lesson that has meaning beyond the individual case. One that focuses on how pre-trial detention, imprisonment and reintegration are handled in this country.

Because: Brian is not an isolated case. Again and again there are inmates who push the system to its limits. But they never appear in the media limelight.

How do we deal with dangerous people?

One question stands above everything: How should society, how should the judiciary deal with potentially dangerous people? With people who have become murderers, with thugs who have seriously injured others, with rapists and with men or women who have abused children? With offenders, in other words, where it cannot be ruled out with certainty that they will become perpetrators again.

The judicial authorities are practicing a balancing act: they have to ensure that criminals serve a sentence for their crimes. In addition, there was something else in the recent past: the judiciary should increasingly ensure that possible crimes are prevented in advance.

But – and this is essential – the authorities must also ensure that the vast majority of perpetrators become work colleagues and neighbors again. Because 99 percent of all prisoners are released again. With around 6,300 men and women currently in prison in Switzerland, that is more than 6,200 people.

Punish, prevent future acts – and at the same time resocialize: Can one be done without neglecting the other? Or is it not more like the former head of the Zurich correctional system, Thomas Manhart, recently in the “Club” program on Swiss television said: “A prison sentence is always counterproductive for those affected.” A stay in prison always hurts.

One thing is clear: The Brian case has relentlessly exposed the gaps and errors in the penal system. It is up to the authorities to find solutions, even in the most difficult cases – and, if errors occur, to investigate them and draw the consequences. Mistakes were also made in the Brian case, and lessons must be learned from that.

When in doubt, for safety

Brian may be an exception. However, his case cannot be explained without considering the social developments of recent years.

The enforcement authorities have become more cautious, zero risk is the buzzword. They only release prisoners if they can keep the risk of recidivism as low as possible. Conditional layoffs are granted much more reluctantly than in the past.

This also deprives the prisoners of the opportunity to prove themselves in freedom. Leaving perpetrators behind bars promises security, but it also delays the moment of their return to society. The chances of reintegration do not get any better.

There are reasons for this development: In the last few decades, there have been a number of tragic criminal cases that have changed the way we look at the penal system.

The rethinking began in Switzerland in the early 1990s. On October 30, 1993, a convicted criminal killed a twenty-year-old girl scout in Zollikerberg. The man was serving a life sentence for two murders and ten rapes. Nevertheless, he was granted leave of absence. And promptly he struck again.

Five years later, a 13-year-old girl was raped and strangled by a repeat offender in the St. Gallen Rhine Valley. The girl only survived by playing dead. The perpetrator was finally sentenced to 18 years in prison. Outraged by the verdict, the girl’s mother and goddess launched the incarceration initiative, which called for lifelong incarceration for untreatable, extremely dangerous sexual and violent offenders – and was accepted by the people in 2004.

Almost ten years later, another case shook Switzerland. While on leave, a criminal kidnapped his therapist and cut her throat in a wooded area. The man previously convicted of two rapes was previously in the La Pâquerette center. The murder revealed outrageous misconduct in the Geneva rehabilitation center, which has since been closed.

The incidents were not without consequences, because since then the authorities, courts and judiciary have been: if in doubt, for safety. No one wants to be responsible when a convicted felon re-offends.

Fear, however, is a poor advisor for serious predictions about the risk of relapse.

The paradigm shift therefore has a downside: criminals are increasingly under a kind of burden of proof that they no longer become criminals when they are free. Only: How are they supposed to be able to prove that behind bars?

This development is also reflected in the case of Brian. The public prosecutor has already demanded proper custody for the young man – even though he is not a capital criminal, but a thug. To date, he has committed two serious crimes while at liberty. A report based on files and his behavior behind prison walls speak against him.

Lessons from the extreme case

Politicians and the media public have a tendency to orientate themselves towards extreme cases. A look at the past shows this: It was only the official misconduct in cases like the one on Zollikerberg that ensured that greater attention was paid to the risk of recidivism by criminals – and rightly so.

Apparently, someone like Brian is now needed to change the way inmates are treated and to improve deficiencies in pre-trial detention and the penal system. Zurich Justice Director Jacqueline Fehr recently described Brian as a “system cracker”. And indeed, there are some lessons to be learned:

- Brian spent more than three years in solitary confinement in the Pöschwies prison – in the cell 23 hours a day, largely isolated from the outside world. Such prolonged solitary confinement is harmful. Of course there are prisoners who can only be calmed down with isolation – for their own protection or that of the guards. But: solitary confinement must be a last resort, an ultima ratio, and not a permanent condition. For example, a legally regulated maximum time limit for solitary confinement could be discussed.

- Special cases require special measures. Most offenders keep quiet in prisons. But there are exceptions. They need the possibility of special settings. The more an inmate rebels, the harsher the reaction of the justice system must be: this attitude does not work in certain extreme cases.

- When a suspect is taken into custody, it often comes as a shock. In order to prevent escape, collusion or the destruction of evidence, the authorities massively restrict the freedom of movement of those affected. At the same time, they are presumed innocent. Some efforts have already been made in the canton of Zurich to mitigate the so-called detention shock. For example, detainees on remand are allowed to spend part of the day in group detention and are given more employment opportunities. But: In Switzerland, unlike in Austria, for example, there is no upper limit for pre-trial detention. The only thing that is stipulated is that the pre-trial detention must be proportionate and must not exceed the expected prison sentence. Here, too, an upper limit would have to be discussed.

- A debate has recently started in specialist circles in Switzerland about the question of whether it would not make more sense to impose harsher prison sentences instead of incarceration. This would circumvent the problem of having to assess the dangerousness of criminals using forecasts and reports. However, there is also a risk that dangerous criminals will fall through the cracks if custody is removed.

It would be wrong to measure the Swiss judiciary solely on a case like Brian’s. In principle, the system, which is geared towards the rehabilitation of offenders, works well. If criminal law and enforcement are applied and further developed with a sense of proportion, they are useful instruments for meeting society’s needs for protection and smooth reintegration.

Criminal law and enforcement must also be prepared for “system crackers” like Brian.