- The thorny problem of the lunar relay

- Chang’e 6, a large lunar vehicle!

- A complex architecture, without any possible error

- On the Moon, a scientific adventure

China can operate in vain an orbital station around the Earth and preparing the future steps of its astronauts on the Moon, its robotic lunar program continues. Always more ambitious! Chang’e 6 will leave next year to bring back the first samples from the far side of the Moon. A unique mission…

Discreet, and even relatively slow in its beginnings, the Chang’e lunar program has been widely talked about for a decade. It has become a true technological showcase of Chinese space know-how. In 2013, the project achieved its first landing with a small rover (Chang’e 3). Then, the teams did it again in 2018, with Chang’e 4, which became the very first vehicle in the world to operate on the opposite surface of the Moon.

Chang’e 5, finally, succeeded in bringing back samples from the Rümker lunar volcanic region in 2020. This 1.7 kilograms of material was the pride of the Chinese exploration program as much as the joy of scientists. With Chang’e 6 in 2024, progress is constant. This time, China wants to bring back even more samples by looking for them on the hidden side.

The thorny problem of the lunar relay

With the tidal effect which “blocks” it in synchronous rotation, the Moon always presents the same face to the Earth. This is particularly interesting when it comes to sending visible-side missions, because at least the antennas can still point at our planet. But conversely, to explore the hidden side, the missions are much more complex.

For probes and orbiters, it is entirely possible for them to capture images which they then transmit to Earth when the latter comes back into line of sight. But for landers and surface missions, it’s not as simple, so you need a vehicle that relays communications. Here again, the matter is complex. China found an original solution in 2018, by sending its Queqiao relay around the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange point.

From this position, Queqiao makes a sort of “8” behind the Moon, having the Earth in its field of vision for very long periods. This solution works, even though Queqiao was only the first generation of this kind of relay. Derived from a communications satellite, the vehicle was not sufficiently protected against charged particles, used a lot of fuel and saw its connection with the Earth or the Moon cut several times. These hazards still allowed China to fully understand the problems, knowing that it is the only agency in the world to have a lunar relay.

It is thanks to this feedback that its next relay, Queqiao 2, which should take off in the first quarter of 2024, will use another orbit, a very pronounced ellipse around the Moon. It will remain visible practically 20 hours a day from the hidden side. It is a large probe weighing 1.2 tonnes, with a parabolic antenna 4.2 meters in diameter.

Chang’e 6, a large lunar vehicle!

Chinese lunar sample recovery missions are (for now) the most imposing sets to land on the Moon in the 21ste century. 8.2 tonnes on the scale at takeoff, a 53-day mission, and above all, it is an assembly of imposing vehicles all capable of operating independently. To take off, it needs a Long March 5 launcher, the most powerful in China’s vast arsenal. The launch is currently planned for the second quarter, although most Chinese lunar missions have taken place in the fall so far.

The three major elements are all powered by solar panels and batteries, and for two months, everything must go perfectly. Objective: this time to bring back 2 kilos, taken from the south of the Apollo crater, not far from the “Lunar South Pole”. The wink will be as political as it is scientific, because this particular area is also the subject of American attention for future sampling. Researchers believe that very old materials from the lunar mantle (during its formation, therefore, before the numerous eruptions and the constant bombardment of asteroids) could be brought back to precisely date its formation.

A complex architecture, without any possible error

Chang’e 6 is therefore an assembly of several elements, each of which is essential. The first is the orbital module, which will first be responsible for navigation to the Moon, then insertion into orbit. This time, the landing site is much further south than for Chang’e 5, so it will be necessary to prepare the approach maneuvers well in advance. Knowing that the orbital module, as its name suggests, will not land. It will separate from the lander module at an altitude of a few tens of kilometers above the lunar surface, and it is the latter which will land, always a difficult exercise, but one that China has historically mastered over the last decade.

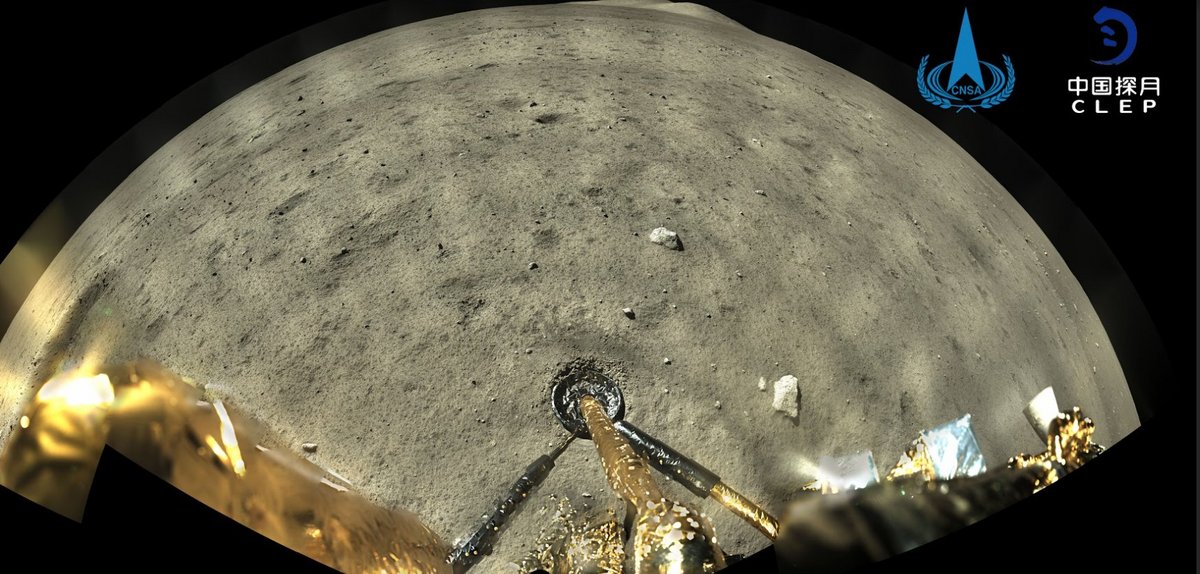

Once on the surface, the lander deploys the scientific instruments and recovers the samples, whether the regolith on the surface with a small collector (a shovel) or deeper, with a drill. The samples are transferred to a sealed container which contains several watertight compartments.

The lander is also separated into two parts, since after a few days on the surface, the ascent module takes off from the Moon to return to its orbit. What follows is an automated approach and docking maneuver that China, once again, knows well, because it practices it regularly around the Earth. The ascent module docks with the orbital module and transfers the samples, which are then stored in the capsule bound for Earth.

Before changing its orbit and leaving again, the ascent module is released. The orbital module returns to Earth in a few days. It drops the capsule precisely for its landing in the desert in northeast China, then it can (depending on the propellants still available or not) continue its mission with an extension, to test a particular orbit or, with a lot of luck, fly over an asteroid. But the most important thing is not there. Once on Earth, the capsule is transferred to Beijing, then isolated in a sterile environment before being opened.

On the Moon, a scientific adventure

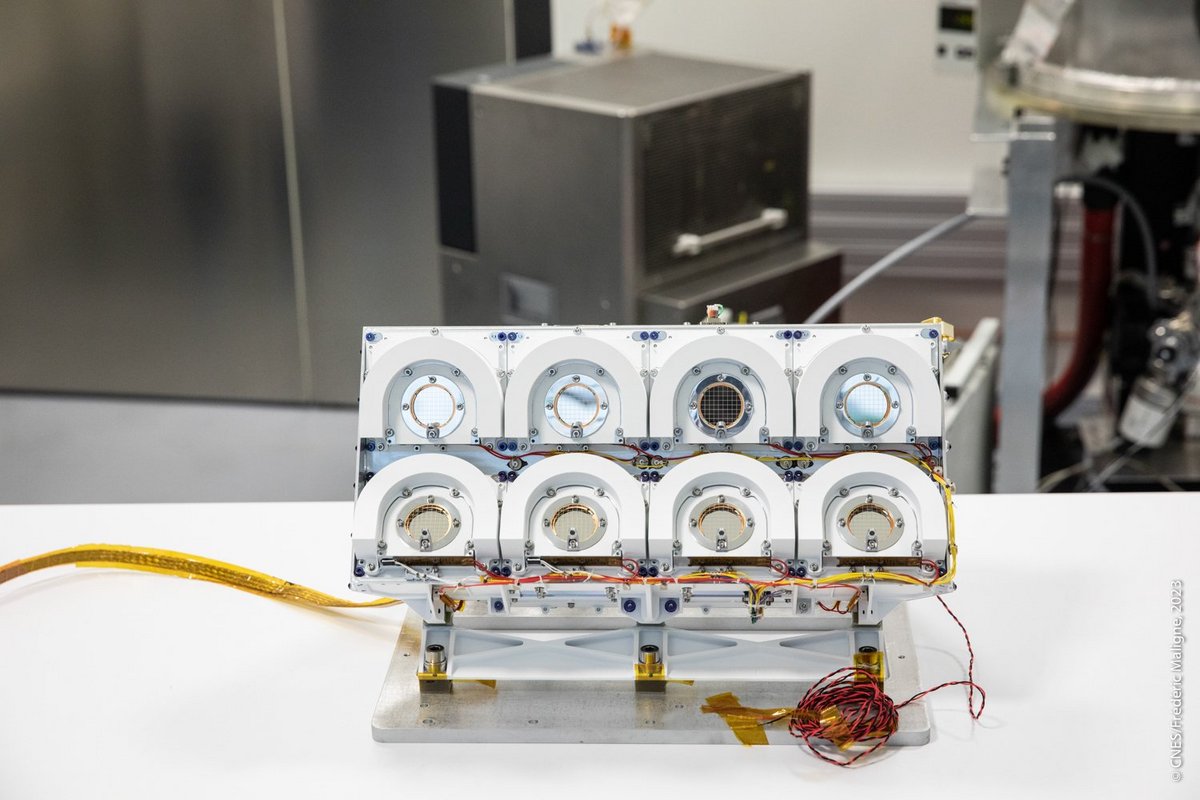

In addition to a small Pakistani satellite (ICECUBE-Q), the Chang’e 6 mission will carry several scientific instruments to the lunar surface, where they will remain active for at least 48 hours (Italy sent a laser retroreflector, which is passive and which will be used to locate the landing site precisely). Sweden sent a small instrument called NILS (Negative Ions on Lunar Surface), while the French agency, CNES, is participating in the Chang’e 6 mission with its DORN instrument.

The latter will measure the concentrations and disintegration of radon around the lander to better understand the degassing coming from the crust and lunar regolith, and also better characterize the exosphere (the superfine atmosphere, almost non-existent, but made up of a few particles) of the Moon. These are not the first collaborations between China and European nations, but it is a small additional step. Let us point out that China is trying to open up to foreign scientific work, in particular for its future lunar adventures. In less than a decade, it should benefit from a permanent robotic ground station, the ILRS.

If China succeeds in this feat with Chang’e 6, the Chang’e 7 and 8 missions, which are already on track, plan different objectives, with the return of a rover to Chang’e 7 (accompanied this time by a “hopper”, a jumping robot) before pre-installation of the ILRS around 2028, depending on the launchers available to take as much material as possible to the Moon. The technological achievement represented by returning samples from the hidden side will perhaps be surpassed a few years later!

3