The historian Regula Bochsler tells the breathtaking story of the origins of today’s Ems-Chemie – including Nazis, nylon and napalm.

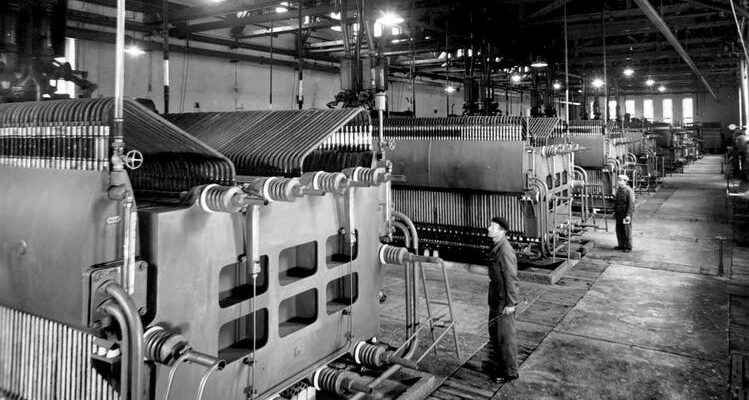

View of the machine room: electrolysers in Ems in 1953.

Werner Oswald, head of Holzverzuckerungs-AG (Hovag), is enthusiastic about the new wonder weapon. Without further ado, he invites a delegation from the Federal Military Department to his kingdom in Ems, Graubünden. He wants to demonstrate his “improved napalm”. On October 20, 1952, two federal ammunition specialists arrived at the factory site, where they were given a three-hour demonstration of experiments with “Opalm” – in the laboratory and outdoors. To simulate bombing, plastic bags containing 70 kilograms of fuel are thrown into a sand pit and ignited. “Opalm” is also busily torched on the plant’s waste water stream.

But the federal government doesn’t want to hear anything about the Swiss variant of American napalm, with which entire regions were bombed and charred during the Korean War: too expensive compared to the foreign competition. And so the destructive product from Ems will soon be delivered to buyers from all over the world, to Burma, Pakistan, Indonesia or Egypt, via tortuous routes. With bomb casings and detonators.

It is just one irritating episode of many that Regula Bochsler describes in her book about the business of Emser Werke and its founder Werner Oswald. The historian researched the subject for four years and, despite being denied access to the company archive, brought astonishing things to light about what she writes as an “almost iconic Swiss company that attracts the active service generation because of the substitute fuel and younger generations because of the previous owner, former Federal Councilor Christoph Blocher. knew». Today, Ems-Chemie is managed by Blocher’s daughter Magdalena Martullo-Blocher, even more successfully than under her highly successful father. She now heads a group with 3,000 employees and annual sales of more than two billion francs.

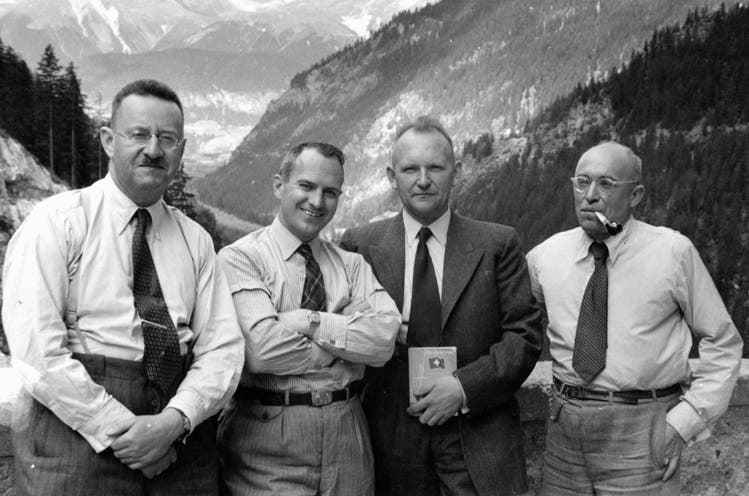

German specialists in Graubünden: Hovag employees Hermann Zorn, Kurt Kahr, Carl Mayer and Paul Kümmel, 1950.

Bochsler’s research began with two metal boxes and a dusty archive box that the son of a former research manager at the company showed the historian. It contained references to explosive transactions and knowledge transfers, which were simply missing in the previously published commissioned works. Only the so-called Bergier Commission took a closer look – or wanted to take a closer look, but only with a focus on the Second World War. Bochsler is also interested in this history, but she is primarily interested in the first decades of the Cold War: “I didn’t want to write a history of Ems-Chemie under Christoph Blocher, I just wanted to find out how Werner Oswald managed to close the war fuel factory into a self-supporting chemical plant and which networks he was able to draw on in the process.» The approximately 550-page study is more than a reconstruction of an individual company, it also tells a chapter of post-war history that is characterized by a spirit of optimism, opportunism and felt in politics and business.

Subsidyitis in Ems

The agricultural engineer Werner Oswald, born in 1904 and from a good family – his father was called the “Kaiser von Luzern” – founded Holzverzuckerungs-AG in 1936. Using a chemical process, he wants to produce substitute fuel for motor vehicles from wood and thus secure a livelihood for the mountain population. The right-wing conservative Oswald is driven by a mixture of patriotism and profit-seeking. Subordinates describe him as bossy, short-tempered and suspicious. His dealings were opaque from the start: in 1937, Oswald and his brother Victor, who maintained good contacts with General Franco, were targeted by the federal police because of suspected arms deals in Spain. The investigation is dropped, but a fiche on the Oswald brothers is created.

Young Werner Oswald, founder of Hovag.

Werner Oswald is a go-getter who dares to try new things, thinks big – and promises a lot. With the outbreak of the Second World War, his Hovag was suddenly in demand because fuel was running out. With 15 million francs from the coffers of the federal government and the canton of Graubünden, he built a factory out of the ground in Ems – actually a madness, away from the major transit lines, only accessible by a narrow-gauge railway. There are delays and breakdowns, but the “Emser Wasser”, with which the imported fuel is stretched from the early 1940s, is significantly in short supply – and creates jobs. However, the much-vaunted self-sufficiency is primarily rhetoric in the sense of intellectual national defense. It also needs raw materials from Franco Spain and Nazi Germany for production.

Oswald presents himself as a homeland protector and knows that lobbying is crucial for an entrepreneur who depends on the state drip. He cleverly gathered influential men around him, such as Armin Meili, member of the National Council and former director of the 1939 state exhibition, or Andreas Gadient, member of the National Council and Government of Graubünden, who would in future act as a kind of propaganda minister for the Hovag. But the socialist Robert Grimm, once the leader of the state strike and now president of the federal Hovag monitoring commission, is also close to him.

After 1945, Oswald’s unprofitable production loses its raison d’être: Gasoline flows into the country again in abundance and at low prices. In order to ensure the survival of the Hovag, the federal government grants it a ten-year, subsidized transitional period, with a guaranteed purchase of the “Emser water”. In 1946, the Hovag annual report stated that they were working “with full force” on the production changeover.

Regula Bochsler has impressively traced what that means in concrete terms, based on extensive research at home and abroad. In places it reads like a spy novel, with colorful characters and shady deals. Sometimes the book is a bit too detailed and anecdotal.

Nazis as advisors

Werner Oswald seeks advice on the realignment of Hovag from Ernst Fischer, formerly head of the mineral oil department in Hitler’s Reich Ministry of Economics and confidant of Reich Marshal Göring. The Allies demanded his extradition, but the Nazi remained unmolested in Switzerland, also thanks to the support of politicians such as Robert Grimm. According to Bochsler, the cooperation between Hovag and Fischer is treated with the utmost discretion. When and under what conditions Fischer will start working for Oswald remains uncertain. It is very likely that Fischer established contact between the Hovag boss and a Nazi chemist who would be of central importance to the company’s post-war history: Johann Giesen, a former director at the I.-G.-Farben plant in Leuna. Giesen was not charged in the Nuremberg war crimes trial against the managers of I.G. Farben, but testified there: in favor of Heinrich Bütefisch, a member of the board. Bütefisch is convicted and, after serving his sentence, is also employed by Oswald as a consultant.

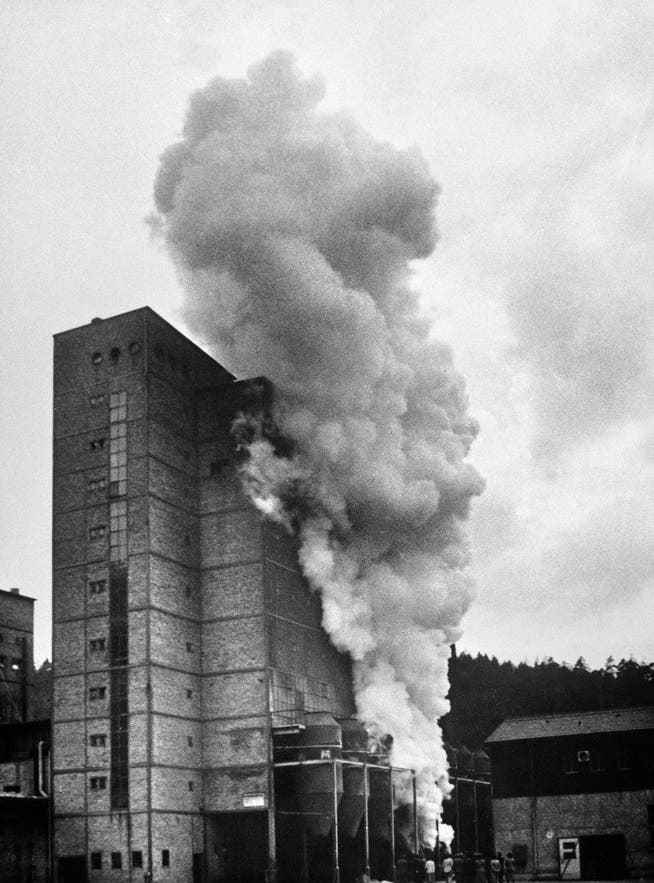

Big ideas and sometimes a lot of smoke: Wood saccharification factory in Ems.

The Swiss entrepreneur has come up with a plan: synthetic fibers are to be manufactured in Ems in the future. Johann Giesen undertakes to procure the necessary production documents and specialists. Thanks to imported knowledge and industrial espionage, a lot of time can be saved. And so chemists are gradually being steered to Ems from war-torn Germany. The bureaucratic hurdles are high, especially for former NSDAP members. However, the Swiss authorities often prioritize the interests of business over political concerns. According to the immigration police in 1947, “it could not be the task of the Swiss authorities to first ask the Allies whether a specialist could come to Switzerland or remain in Switzerland”. And anyway, aren’t the Americans doing exactly the same thing by bringing the best Nazi scientists to the United States, such as the rocket builder Wernher von Braun?

Werner Oswald sees it that way too. He can also count on a friend from the military, Paul Schaufelberger, who is now a senior officer in the intelligence service. He has contacts with a smugglers’ office in Bern’s Marktgasse, which brings German scientists across the green border into Switzerland and then on to Argentina. Schaufelberger does nothing against the “rat line”, but in return taps into the expertise of the researchers. Oswald also benefits by gaining know-how and specialists for the Hovag in this way. But that’s not all: Plans for plants and machines are also needed. Oswald doesn’t shy away from procuring blueprints that were stolen from German factories.

Synthetic fibers as a new business model: Employees in the spool control department in 1953.

Only in this way is it possible for Oswald to announce as early as 1950 that the first synthetic fiber to come entirely from Switzerland would now be manufactured in Ems – brand name Grilon, a word mixture of Graubünden and nylon. “The Grilon production is the largest, most ambitious and, in the long term, most successful project that he tackled after the war,” writes the historian Bochsler. But she also addresses other lines of business that are being pursued. For example, the development of an anti-aircraft missile, again with the help of former Nazis, this time by the Peenemünde Army Research Institute, where the legendary V2 missile was developed. Later, Oswald’s researchers also tinkered with napalm, detonators and anti-personnel mines.

“The Swiss people tricked”

In 1955, the Federal Council came to the conclusion that the Hovag was still not viable and would have to be supported for another five years. Economic liberal circles are outraged by the “senseless” planned economy. They launch a referendum and win in the spring of 1956 after an extremely hateful campaign in which Hovag warned of impending ruin.

But the prophesied demise of the Hovag does not occur. On the contrary. After a year without federal aid, the company is thriving like never before. “Let’s admit it: Hovag has fooled the entire Swiss people, including the government,” says the “Weltwoche” annoyed. Hovag blames “some particularly fortunate circumstances” for the success, such as successful research projects and the good economy.

Without access to the company archive, the historian Bochsler cannot clearly explain how the “Miracle of Ems” actually came about. Because with the end of federal aid, the documents publicly available for research also end. The fact that relevant files are stored in Ems has been known since the investigations of the Bergier Commission, which had exclusive access. The suspicion remains that undesirable research was prevented here. And so much in this study inevitably remains vague. Clandestine transactions and informal contacts are naturally difficult to prove. Especially since Werner Oswald deliberately set up a cleverly nested group that the federal surveillance commission could hardly penetrate.

It is clear that Oswald was able to build up a corporation with millions and millions of francs in tax money and realign it with the help of researchers from Germany. At his death in 1979, this consisted of twelve companies and a holding company, estimated to be worth half a billion francs.

Regula Bochsler: Nylon and napalm. The business of Emser Werke and its founder Werner Oswald. Verlag Hier und Now, Zurich 2022. 595 pages, CHF 49.90.