Internet users have released “digitine” (digital + guillotine) by blocking celebrities on social networks. But is it really a revolution? This is the subject of this issue of our Règle30 newsletter.

One of my favorite corners of the internet is called Oh No They Didn’t. In this old online community, born in 2004 (!) and hosted on Livejournal (!!), we exchange gossip about the stars. I like spending time there because it amuses me, and also because it informs me about a part of popular culture that I have little control over. “ [On doit] be interested in the messages conveyed by celebrities, because they are sometimes more listened to and influential than politicians or researchers », wrote independent journalist (and my friend) Morgane Giuliani in her essay Feminisms and music (The Word and the rest, 2023). “ It is we who decide to give them success and therefore power. »

Last week, a group of Internet users decided to turn off the tap. It all started with online content creator Hayley Baylee, who shared a video of herself getting ready for the Met Gala over a clip from the film Marie Antoinette by Sofia Coppola. Not too surprisingly, the vision of a woman in her Sunday best, imitating a popular symbol of inequalities between the rich and the poor, did not delight the crowds. The influencer has received widespread criticism and inspired calls to release the digitin (digital + guillotine): since we can’t literally get rid of celebrities, we can at least ignore them by blocking them on all social networks.

The #Blockout2024 movement

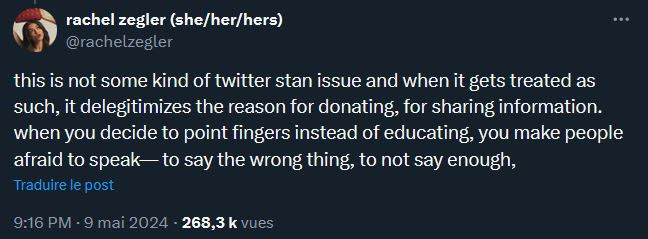

A chaotic movement ensued. Several lists of stars to be blocked online have circulated under the name #blockout2024, most aimed at Met Gala guests, others more general. These celebrities are accused of being too privileged, and above all too silent in the context of the war waged by Israel since October 2023, which has caused more than 35,000 deaths in Palestine, the majority of them civilians. But other personalities, quite vocal about the conflict, were also attacked, such as actress Rachel Zegler, who defended herself on her Twitter/X account.

It makes sense that such dramatic news would reinforce our unease online. The platforms we operate on are not, by nature, suited to handling bad news, even more so in our era of algorithmic recommendation feeds. We have the choice between drowning in a torrent of unbearable images or alternating between innocent publications and those testifying to the violence in progress.

We can also ask ourselves what, exactly, we expect from celebrities, contradictory parables of our desires and our anxieties. Would an Instagram post from Taylor Swift calling for a ceasefire in Gaza really satisfy us? When do we accept being entertained, when does it become unbearable?

Despite its revolutionary imagery, the digitine movement does not call for disrupting our current media system. We remain in a logic of influence. We accept the rules in place. There are, however, legitimate things to criticize, such as the increasingly assertive refusal of platforms to host content considered political (without specifying what is, in their eyes, political) and their ultra-centralized, automated, where only a few accounts and topics can survive. This is the origin of power. By taking out the digitine, we are not calling into question the power of the stars: we are asking them to use their unfair privileges for a just cause. Is it sufficient ?

This article is taken from our Règle30 newsletter, every Wednesday morning in your inbox. Subscribe :

Subscribe for free to Artificielles, our newsletter on AI, designed by AIs, verified by Numerama!