Herculaneum scroll being digitized at the Institut de France by Brent Seales and his team. EduceLab.

Two thousand years after a historic volcanic eruption, researchers managed to decipher mysterious ancient scrolls with AI. They now know what at least one Roman Epicurean philosopher had in mind: food.

Undoubtedly proof that humans, although full of surprises, can be endearing and predictable.

This revelation is the culmination of the Vesuvius Challenge, a competition launched in March 2023 by Brent Seales, researcher at the University of Kentucky and Nat Friedman, former CEO of GitHub.

Three students win $700,000

The goal was to take tomograms of what are known as the Herculaneum Scrolls. Then, software based on machine learning had to carry out a detailed analysis. And everything had to be put in the hands of fine sleuths. The idea? That someone could finally read the scrolls, without even touching them.

The organizers promised – with the support of actors from Silicon Valley – a prize in hard cash to encourage action. 700,000 dollars will therefore be distributed between the three members of the winning team: Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor and Julian Schilliger, all three students.

They deciphered 15 columns of text from the manuscript, which preliminary analysis suggests is a text that attempts to answer the question of whether the scarcity or abundance of goods such as food influences on pleasure.

200 new ancient books thanks to AI

The challenge of Vesuvius marks a turning point in the quest to decipher these parchments. It’s also an important moment for Brent Seales, who has been trying to achieve this for twenty years.

The contributions, according to Mr. Seales, represent approximately 10 years of human work. They were completed in… just three months. “It’s amazing to feel this power that we now have thanks to AI, tomography and computing,” Mr Seales said.

Michael McOsker, a researcher who has studied the scrolls, estimates that all of this effort could result in the creation of around 200 new books. Particularly rare works since this collection is also the only surviving library from Antiquity.

“We probably have less than 1 percent of all the literature that has been written,” he said. “Any progress in our knowledge is important.”

History unfolding before our eyes

Brent Seales and Seth Parker (Digital Restoration Project Manager) scanning a replica of the Herculaneum Scroll. Picture UK

Brent Seales is an imaging specialist interested in AI. The problem is that there hasn’t been much to sink our teeth into when it comes to AI for 20 years. Computer vision, however, has progressed little by little.

In the mid-1990s, he met a professor who was working on a manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf. This was the period when efforts were being made to digitize libraries. Having read Beowulf in high school, Seales was stung. He reflected on the power of digitizing this text, the only existing manuscript that bears witness to history.

And digitalization has transformed into restoration. Once the text is scanned, the image quality can be improved. Making a copy is not necessarily an end in itself. And if we could digitally flatten a crumpled document, couldn’t we also digitally unroll a handwritten scroll?

The technology was invented before finding the use case

Clearly, as is often the case, the technology was invented before finding the use case.

But in 2004, Mr. Seales finally found something to unwind. A classical scholar, Richard Janko, told him he had found the ideal solution for exploring the Herculaneum scrolls.

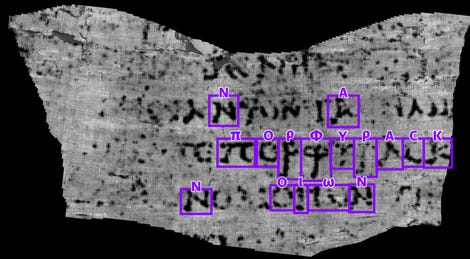

The Greek characters, πορφύραc, revealed as the word “purple”, are among many characters and lines of text that have been extracted by Vesuvius Challenge contestant Luke Farritor.

Digging up the past

Today, the eruption of Vesuvius certainly conjures up images of bodies buried in ash, huddled together as their world ends. This historical event is fascinating, tragic and a little frightening all at the same time.

The only record of the period comes from the letters of the Roman author and jurist Pliny the Younger, who describes panicked crowds and a “thick black cloud” that consumed the earth. “Some people were so afraid of dying that they prayed for death,” he writes.

When the cloud had thinned enough to allow daylight to pass through, Pliny the Younger saw a layer of ash that had buried everything, and it reminded him of snow.

The challenge of Vesuvius

In Herculaneum, a town about 15 km west of Pompeii and even closer to the erupting volcano, ash and debris engulfed a villa that belonged to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law. The villa housed a library of papyrus scrolls.

Although a 2 meter thickness of hot ash may seem fateful to the papyri, the heat charred the scrolls, preserving them from the natural deteriorating effects of the air.

It was only in the 1700s that a farmer, while digging a well, found marble, which kicked off the excavations which uncovered more than 600 parchments.

This is not an “experience”

Today, the scrolls are kept in several places in Europe, with the majority being in the National Library in Naples, Italy.

It took Mr. Seales years to build a case and gain access to these documents.

Mr Seales, who had a background in surgical innovations – such as laparoscopy – wanted to use computer tomography to scan the scrolls and then create software to wrap those scans.

In 2005, Mr. Seales presented a papyrus encased in a polyurethane sphere, which he had scanned and virtually unrolled. The reaction was positive, but to conservative ears it still sounded a lot like an experiment, and “experiment” is a dirty word when it comes to something so rare and so old.

After four years of hard work, in 2009, Seales and his team traveled to the Institut de France to perform their first micro-CT scans of the papyri.

“I was both terrified and incredibly excited,” Mr Seales said. The rolls were very small and looked like charcoal. “It’s a whole book of antiquity…but it’s just a little tiny thing because it shrank during carbonization.”

Trial and error

Over the past 20 years, Seales’ research team has had the opportunity to work on other manuscripts.

In 2006, Seale’s team unrolled a medieval copy of the Book of Ecclesiastes written in Hebrew. A year later, in 2007, Mr. Seales was part of a team that traveled to Venice to digitize the oldest complete copy of Homer’s Iliad.

Herculaneum Scroll being scanned at the Diamond Light Source inside its scanning case. EduceLab

“Each of the projects I have carried out has strengthened my credibility as a researcher and allowed me to acquire the knowledge necessary to approach the decision-makers at these museums and libraries,” he says.

In 2013, he spent a year in Paris as a visiting scientist at the Google Cultural Institute. This stay allowed him to become familiar with new people and new ideas, just as Google was about to acquire the artificial intelligence research laboratory DeepMind.

It was at this time that Mr Seales began investigating the possibility of performing scans in a particle accelerator, which would significantly improve the resolution of the images.

Discerning gray from gray

One of the main problems is so-called segmentation. Although the scrolls are quite small, the scans are detailed. Technical lead Stephen Parsons describes efforts to digitally separate layers of partially crushed papyrus and the network of fibers visible in the scans. It looks a bit like a cross section of a somewhat crushed tree trunk.

Another challenge was reading the ink on the papyrus. According to Parsons, the best imaging technology they have for seeing inside the scrolls is the micro x-ray scanner. The problem? The contrast is not sufficient to read the ink.

For what ? Because the Herculaneum Scrolls were written with soot from oil lamps, which is chemically almost pure carbon. Since papyrus is also chemically composed of carbon, the team found themselves faced with gray upon gray.

Other projects have not encountered this problem. The En-Gedi Scroll in 2016 – the oldest scroll of the Pentateuch (relating to the first five books of the Bible) since the Dead Sea Scrolls – whose successful digital unwrapping was a major milestone for Seales’ team – has ink containing iron. And this iron appears as bright spots in X-rays.

For the Herculaneum scrolls, Parsons says he hypothesized that there might still be a detectable difference between the ink and paper. He compares it to lines painted black on the asphalt. Perhaps a machine learning model could be trained to see ink he wondered.

It took years of work to test this idea. The tests took place on parchments made by the research team, and on fragments of parchments from Herculaneum.

“That’s when it all became clear. Although it takes many years to develop and refine, this approach will eventually pay off,” Parsons said. A year later, it was done.

A software problem

But segmenting and detecting ink is only part of the overall challenge of reading these scrolls. The exploitation of data and its algorithmic sorting are another challenge.

After several iterations, Seales’ team created Volume Cartographer, developed primarily by project manager Seth Parker, who joined the team in 2012. It is open source software used to map the interior of rolls and make sense of the “soup of floating words,” as Parker put it.

The 12 pezzi, or “pieces”, of the opened Herculaneum papyrus scroll, known as P.Herc.118. This compilation of images is the property of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. The challenge of Vesuvius

Continue to unwind

If 15 columns of text is more than Seales expected, that’s not the end of the story.

Longer term, Parker and Parsons imagine their work could also inspire other fields using dimensional imaging.

CT scans and MRIs are already very good, but what about information hidden from the naked eye of doctors that could improve the detection of tumors, for example? “There are ways to transform this data to make it easier for a human to interpret,” Parker said.

“There’s no reason to slow down. Let’s read the entire library,” said student and team member Luke Farritor. The challenge of Vesuvius

And there are still ancient texts to read. At the same time, they are working on a medieval manuscript, a Coptic gospel whose pages have been merged. They have carried out numerous scans and are again trying to virtually unravel what is written inside.

The short-term goal for 2024 is to read 90% of the scroll started by Nader, Farritor and Schilliger. And yes, there will be even more money at stake. “We’re partying right now, but there’s no reason to slow down. Let’s read the whole library!” Farritor said in a statement.