Peregrine failed to reach the Moon. The first of NASA’s CLPS programs, this failure of the lander postpones the return of the United States to the Moon via private companies.

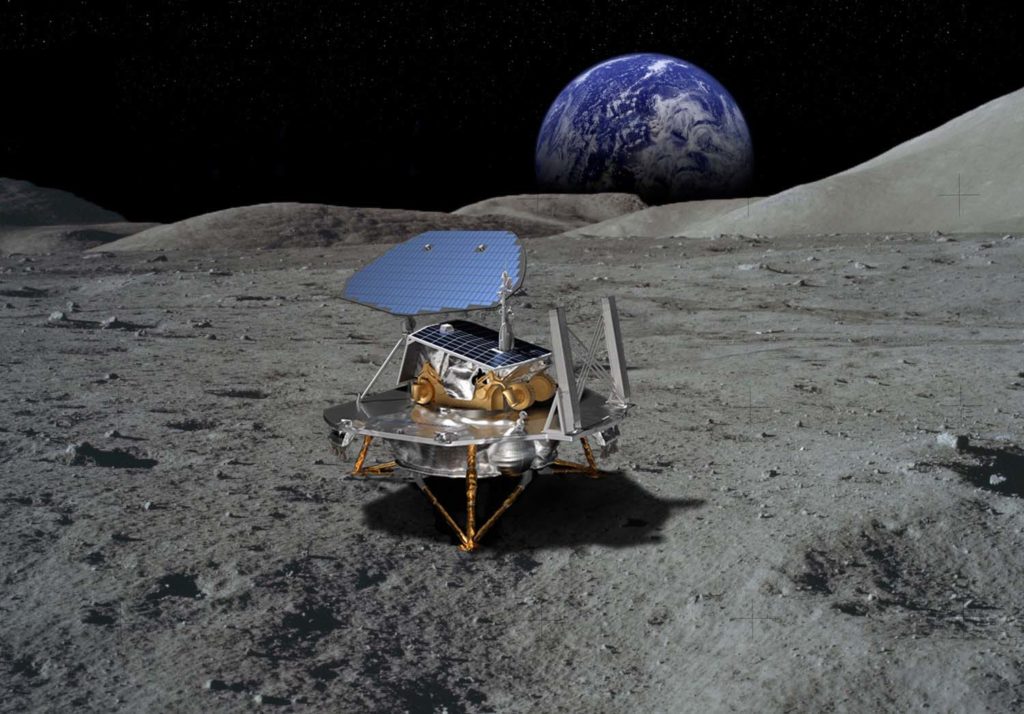

Peregrine should have arrived on the Moon with a hundred kilos of scientific instruments on board, but that is not what happened. Instead, the lander which was to mark the return of an American vessel to the lunar surface after half a century of absence suffered a propellant problem and continues to drift in space. He only has one meager hope left to cling to: that of crashing on the Moon within a few weeks.

Presented like this, the observation is terrible, but as is often the case in space, the reality is a little more nuanced. “ From the start of the mission, it was clear that the risk of failure was 50%.assures Peter Wurz, astrophysicist at the University of Bern. This is the price to pay for a mission that does not cost too much. »

Cheap contracts and risky missions

Indeed, this is the whole point of the CLPS program (“Commercial Lunar Payload Services”), the new NASA system within which missions are entrusted to external service providers. Small companies build vehicles into which the U.S. space agency places its scientific payload. For Peregrine, it was the company Astrobotic, founded in Pittsburgh in 2007, which built the lander. To be selected, the company had submitted a file promising to respect NASA’s conditions in terms of reliability, but also cost, and in the event of an unforeseen event, Astrobotic would issue additional checks to make up the shortfall.

Peregrine was the first CLPS mission, but others will follow. Intuitive Machines must launch the Nova-C probe, also destined for the Moon, by February. The concept is almost the same as for Peregrine, with a lander containing scientific instruments. Astrobotic has also planned other lunar missions, including the VIPER rover scheduled to leave at the end of 2023, even if the date remains very uncertain.

“ There is no reason for Astrobotic to lose its contractsconsiders Peter Wurz. This failure will be used to correct the defects for future launches. All the other companies involved in the CLPS program will undoubtedly also follow this very closely. »

Of course, it would be possible for all these future missions to take a little more time to ensure a slightly higher chance of success. This is not the aim of these contracts designed to be quick and inexpensive. Peter Wurz explains: “ To reach an 80%, or even a 90% chance of success, you need more tests on each component, studies, analyses, or even complete design changes if something goes wrong. This takes time, but also and above all money. If only to pay the people who work on this. We can double or triple the budget. »

“The public also witnesses part of the process”

The CLPS program serves to avoid these cumbersome steps which considerably slow down the development of missions. But if, in the end, the devices explode in flight, where is the benefit? “ It’s ultimately simpler this wayinsists Peter Wurz. All these failed tests, these backtracking… It’s something that was done in the laboratory before. Here, the difference is that it is visible to everyone, but the result is the same: we test, we fail, we learn, and we start again. »

A method reminiscent of that of SpaceX, with its multiple partial rockets exploded on the Boca Chica base. Internal tests could perhaps have better hidden all these spectacular failures, but they would undoubtedly have taken longer and even more expensive to implement. This is how NASA sees Peregrine: a failure in broad daylight that will serve to learn and progress. “ Instead of only seeing the finished product, the audience also witnesses part of the process. »

It is therefore a safe bet that the next CLPS missions will benefit from this first unfortunate experience. Unless the problem experienced by Peregrine corresponds to another probe in preparation, there will be no further delay.

But, what about Artemis? The “real” NASA program which is not managed by external startups? The agency recently announced that the Artemis II missions, and by extension, Artemis III, would leave later than planned, but there is no link with Peregrine. These institutional programs do not follow the same logic as CLPS contracts, and since it involves flying human beings, internal tests will obviously be much more thorough, because there is no question of failure.

“ The estimated success rate for the Apollo missions was around 80%.says Peter Wurz. Today, this would no longer be acceptable, and we want to approach zero risk for manned missions. No one wants to relive the dramas of Challenger or Columbia. »

As for unmanned missions, certainly, Peregrine signifies an American failure. But the same has happened in recent months with Russian, Japanese and Israeli missions. Landing safely on the Moon is still an engineering feat, and we haven’t yet reached the point at which it will be routine.

Subscribe to Numerama on Google News so you don’t miss any news!