After a difficult start, the German Chancellor and the President of the Soviet Union became friends. They understood each other because they thought in historical terms.

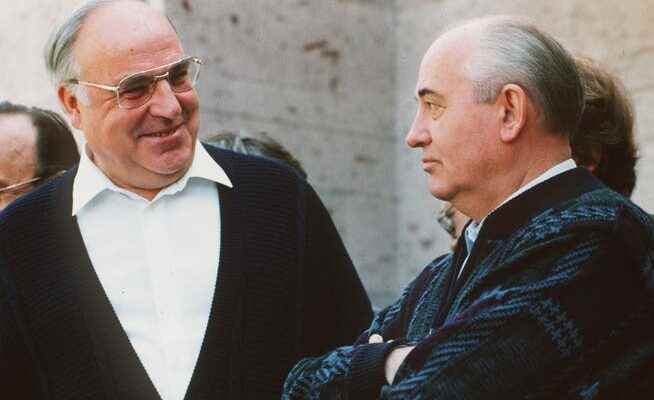

High point of cardigan diplomacy: Kohl and Gorbachev in 1990 in Archys in the Caucasus.

Often the story is a long, sluggish river with occasional backlogs. But sometimes it condenses into a few decisive moments, minutes or hours in which history is really written and the world is different afterwards. Such a moment happened in the summer of 1990 in the Caucasian village of Archys.

There, in a government dacha, the Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev had invited the German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. The two politicians went to the Bolshoi Zelenchuk river, sat on tree stumps, laughed a lot and talked to each other for about four hours. It was July 16, 1990. Only then was it clear that the Soviet Union would not put any obstacles in the way of reunification and the turning of the larger Germany to the West. The fact that the GDR was able to peacefully join the Federal Republic is also the result of a very special and remarkably trusting relationship between Kohl and Gorbachev.

Kohl’s American scandal

This special relationship was by no means a friendship at first sight. Two war children of almost the same age met here who had experienced the Second World War and had grown up on different sides of the Iron Curtain: Kohl in the tranquil Palatinate, Gorbachev in the northern Caucasus, not far from the Ukraine.

Neither the German born in 1930 nor the Russian, who was a year younger, could have guessed that it would be up to them both when world history took a new turn that is still irreversible today. The end of the German Democratic Republic and the Warsaw Pact, and with it the end of the post-war geopolitical order, is inextricably linked to their names.

At most, Helmut Kohl, the ardent European who was concerned about the German question, may have already thought of that when the two men first met. No lasting testimony survives from their meeting at the funeral of Secretary General Chernenko in 1985.

A year later, Kohl caused an uproar when he allowed himself to be carried away in the American magazine Newsweek to compare the new Soviet General Secretary with the Nazi propaganda minister. Gorbachev, “a modern communist leader”, is like Goebbels “an expert in public relations”.

Germany’s unlimited sovereignty

The slandered Russian, in turn, soon afterwards called the chancellor a “lackey of the USA” to the East German Council of State Chairman Erich Honecker. The reason for this was the federal government’s support for the US missile defense system SDI, which the economically ailing Soviet Union had nothing to oppose other than indignation.

Kohl’s ten-point plan of December 1989 was also unpopular in the Kremlin. Although the Berlin Wall had already fallen, the confederation of the two states outlined by Kohl made Moscow fear the closeness to the western alliance that was then accepted in Archys. A mischievously looking chancellor in a blue cardigan, an alert Soviet president in a blue sweater, with Bolshoi Zelenchuk at their feet, documented for the world press how down-to-earth and unpretentious they knew how to deal with each other. There was no protocol between them.

Kohl declared that Germany now had the “unrestricted sovereignty to decide freely and independently whether and to which alliance it wanted to belong”. Gorbachev did not disagree. This even surpassed the Moscow meeting in February of the same year, when Gorbachev and Kohl jointly affirmed “that it is the sole right of the German people to decide whether they want to live together in one state”.

Moscow and Archys was the world-historical duty, which both politicians sufficed to a large extent, Deidesheim the friendly freestyle. Kohl invited almost every important statesman with whom he had more than just a professional relationship to his homeland in the Palatinate, preferably to Mittelhaardt in the pretty wine-growing community of Deidesheim. Vaclav Havel, Boris Yeltsin, John Major, Jacques Chirac, the Spanish royal couple Juan Carlos and Sofia: they were all guests at the “Deidesheimer Hof”.

Saumagen and Riesling for Gorbachev

On Saturday, November 10, 1990, Gorbachev was served baked greaves sausage on apple horseradish vegetables, liver dumplings, Carthusian dumplings on vanilla ice cream and of course the world-famous Saumagen, a spicy specialty made from pork, potatoes, marjoram and nutmeg. There was also Palatinate Riesling from Gorbachev’s birth year of 1931. In the kitchen, reported the almost equally famous chef Manfred Schwarz, Kohl and Gorbachev offered one another the first name. In front of the restaurant, the band of the local Kolping family played the song about the “Hunters from Kurpfalz”.

When Gorbachev spoke before the German Bundestag in 1999, he recalled the decisive events: The unity of Germany had opened up “against the background of general global changes, a perspective for the transition of the world community to a new, peaceful stage in world history”. And he cited Helmut Kohl for his optimism, who had told him “we’ll make it step by step” that two states would become one fatherland.

Kohl, on the other hand, wrote on Gorbachev’s 75th birthday that in 1990 they had spent “a wonderful time together in your datsche” in the Caucasus, at the end of which “the final modalities of the unification of our German fatherland” came to pass. Gorbachev’s German biographer Ignaz Lozo sums up the decisive hours in Archys: “He, above all he, made the reconciliation with the Germans and the reunification of their country possible. This alone would have been enough for the Nobel Peace Prize, which he will be awarded three months later, on October 15, 1990.”

Today, the signed Deidesheim menu rests in the Wine Museum in Mainz-Oppenheim, while Kohl’s cardigan, Gorbachev’s sweater and wooden furniture from Archys can be seen in Bonn’s House of History, the Chancellor of Unity’s favorite memorial project. The extremely momentous history of the German-Russian relationship between Michail and Helmut would also have its place in a museum of immaterial things.