In Germany, groceries are becoming more expensive almost every day. Ironically, the price increase is greatest for the cheap brands – that shows a NZZ data analysis. This effect does not exist in Switzerland.

Groceries from the Rewe brand «ja!» are cheaper than products from well-known manufacturers. But precisely in the crisis, the price advantage is shrinking.

A dispute over food prices is raging in Germany. In the meantime, this is also being conducted quite openly, with visible consequences for customers: in the supermarkets, branded products from American food companies have increasingly been missing lately, at the retail giant Rewe, for example, chocolate bars from Mars, at the discounter Aldi there were no more Pepsi products. The reason: Grocery retailers are often no longer willing to accept manufacturers’ price increases and pass them on to their customers. Instead, they now find empty shelves – often with a reference to their own cheap brands.

“Yes!” is the name of such a private label at Rewe; it is closely linked to the trade brands of the large discounters. In this cheap segment, Aldi usually sets the price, the others follow suit. Price changes at Aldi are almost always reflected one-to-one in Rewe’s “ja!” products. It is similar with other brands such as “Gut & CHEAP” from Edeka.

The price advantage of cheap brands is shrinking

What customers don’t find out in front of the empty supermarket shelves: In parallel to the defensive fight against the price increases of the brand manufacturers, Rewe and Aldi have pitched their own brands even more vigorously. This is shown by a NZZ comparison between the price increases for foodstuffs with the “ja!” brand name. and the average control of all brands; The basis is data that the NZZ has had since mid-April collected daily and published on Twitter. The NZZ has calculated its own inflation rate for each food group – using the same methodology as the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis).

The difference is particularly clear with some important dairy products: while the prices of yoghurt from the “ja!” 47 percent between May and October, the average price increase of yogurt from all brands in the same period was only 17 percent – a difference of 30 percentage points.

Increase in own brands in some cases seven times as high

It was even greater for individual product groups: the price of orange juice at Rewe, for example, rose seven times as much, and the increase in ketchup was more than three times as high. And the many price increases that already took place in the spring are not taken into account at all.

If you look at all the groceries in a shopping basket between May and October, the inflation rate for Rewe own brands was 11.5 percent overall, but the average was 8.9 percent. A typical purchase of “ja!” groceries has therefore become more expensive in percentage terms than a typical purchase of products from all brands.

Cheap meat cheaper than in May

The fact that the difference, at a total of 2.6 percentage points, was smaller than for the product groups mentioned was mainly due to the meat. This hardly got any more expensive in the cheap segment between May and October; Pork from the Rewe own brand «ja!» is even 10 to 13 percent cheaper than in May. Contrary to the general trend, Rewe chocolate is also no longer expensive. If you remove meat and sausage from the shopping basket, the difference between the two inflation rates is already 5 percentage points.

Now prices are picking up again

In November, the price of “ja!” products rose again significantly. These and other price increases have also had an impact on the average inflation rate for food: According to Destatis, it was in November again above the level of the previous month. However, the statistical authority will not publish detailed figures on this until mid-December.

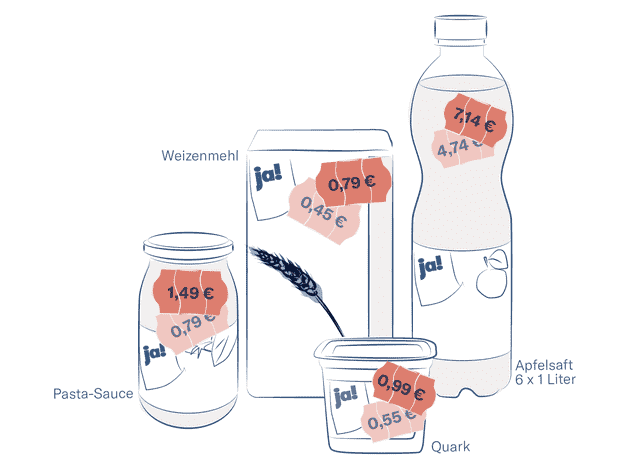

For example, the prices for potato products at Aldi and Rewe increased by a total of up to 67 percent compared to May up to and including the end of November. Juices were also around 50 percent more expensive by the end of November – this is shown by an overview of the largest price increases for individual “ja!” products.

For a kilogram of French fries, customers of the Rewe and Aldi brands now pay 80 cents more than in May, and 34 cents more for wheat flour. A 6-liter pack of apple juice now costs 2.40 euros more in absolute terms.

These price increases should soon pay off even more for retailers. Because as a result of rising energy prices, the Gesellschaft für Verbraucherforschung (GfK) assumes that its own brands will continue to gain market share during the crisis. Measured against sales, these were already 42.8 percent at the end of September – an increase of more than 2 percentage points compared to the previous year.

Consumers on a tighter budget more affected

Low-income households in particular use their own brands: According to an investigation of the price advice Simon-Kucher & Partners in November, two-thirds of the low-income earners surveyed buy predominantly or exclusively in the low-price segment. Relatively speaking, consumers with a small budget are therefore more affected by higher food prices. In absolute terms, private labels are still cheaper than branded products. But the distance is shrinking.

“The last time private label price increases were higher than manufacturer brands was during the 2008 financial crisis,” says Robert Kecskes of the Society for Consumer Research. With a view to the recent crisis, Rewe points to the increased costs of raw materials, energy, logistics and wages. According to Kecskes, these cost increases are proportionally more noticeable for private labels because the margins are calculated more tightly.

According to the economist Joachim Ragnitz, the increasing demand during the crisis could also be a reason why the private labels have increased in price in percentage terms. On behalf of the Ifo Institute, Ragnitz examined how companies in various sectors of the economy used the general trend towards price increases to expand their profits.

Swiss own brands are becoming less expensive

In Switzerland, the situation is different. Even before the Ukraine war, food prices there were about twice as high as in neighboring countries. They also rose significantly less than in Germany, which is mainly due to the fact that the market for many foods is closed off and the Swiss franc is very strong. In recent months, prices for imported products in particular, such as cooking oils and pasta, have increased.

The NZZ carried out an analysis similar to that for the German market for Coop’s own brand “Prix Guarantee”. According to this, inflation for Swiss own brands does not differ significantly from the average price increase for groceries.

For products that are particularly affected by inflation, however, Coop has increased the prices for its own brand significantly more since the spring. In the case of edible fat, the difference compared to the average is around 14 percentage points, and in the case of pasta it is 5. Here, too, the fact that the price increases for raw materials have a greater impact on cheap brands may play a role. Overall, however, the price increases are much lower than in Germany.

Nevertheless, there is good news for German consumers: Hidden price increases due to smaller pack sizes are now coming even with cheap brands, but none is known for the «yes!» foods. At least in the Rewe online shop there was no indication of a so-called “shrinkflation”, as experts also call it, between mid-April and the end of November.

You can see which groceries have become more expensive or cheaper in the past 30 days – updated daily – in the NZZ price monitor for Germany.

This is how the NZZ calculated the inflation rates

The NZZ calculates the inflation rates for its own brands in a similar way to Destatis or the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (BfS). However, the NZZ only shows the development between May and October; the official inflation rates, on the other hand, show the change compared to the same month last year.

The basis used is that used by the statistical offices shopping cart, which contains most of the groceries bought by private households. The NZZ has assigned all Rewe “ja!” and Coop “Prix Guarantee” products to the shopping cart.

Each product group in the shopping cart is given a weight that corresponds to its share of average consumer spending. An example: Bread and grain products have a weight of 1.5 percent in the German shopping basket. So 1.5 percent of the spending of an average household goes on bread, rice, pasta and other grain products.

In order to calculate the inflation rates, the price increases of individual product groups are multiplied by their weight. The sum of all weighted price changes then results in the average inflation rate. However, the assignment of products to a shopping cart and the calculation of inflation rates can be associated with inaccuracies.

Only those product groups that are also covered by our own brands are included in our shopping cart. Rewe «yes!» For example, does not have any fresh fruit or vegetables in its range, which is why these products are not included in the shopping cart. Some other categories, such as cakes and canned fruit, are also not included due to the insufficient number of products.