At the time of reunification, he led the former GDR state party into the German Bundestag, and now he wants to prevent its successor from getting bogged down in identity-political debates. Is Gregor Gysi a man for cases that others consider hopeless?

All-German political entertainer: After the fall of communism, Gregor Gysi became a popular talk show guest in the Federal Republic. Here during an appearance on the ZDF program “Markus Lanz” in February.

History, according to a popular quote from Karl Marx, always happens twice: once as tragedy and once as farce. It remains to be seen whether Gregor Gysi’s latest project will end as a farce, but at least the impression of a reprise is inevitable: the man who saved the former GDR state party SED over the fall of communism and as the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) in the Bundestag, now wants to save the Left Party, which emerged from the PDS in 2007.

Is Gysi a man for cases that others see as hopeless? As a lawyer, the 74-year-old explains in his small office in the Bundestag building that he suffers from an illness: “People with problems always come to me. You need a certain distance because otherwise you will become depressed. But I’m interested in people with problems, and that also applies to organizations or parties.”

In 1990, when the GDR was on its last legs and Gysi advanced to the leadership of the party, he quickly became one of the most hated politicians in all of Germany: as the son of Minister of Culture Klaus Gysi, who grew up in privileged circumstances, for many he was now the string puller who trying to salvage property. The fact that Gysi, as a lawyer in the GDR, had also defended members of the opposition such as the civil rights activists Bärbel Bohley, Robert Havemann and Rudolf Bahro played no role for his opponents. It wasn’t the time for ambivalence.

A smaller office in the Bundestag

Compared to the turning point, Gysi’s new rescue mission has received little attention: Die Linke has become a splinter party that almost missed re-entering parliament in the federal elections last September. In the last legislative period, Gysi reports, he had a larger office, but because his parliamentary group is now much smaller, he had to move. He seems to be taking it easy: The members of the American Congress have much smaller rooms, he explains.

The fact that the Left Party is doing badly is surprising in itself: the Social Democrats and the Greens have been part of the German government for a little over six months. A force that is further to the left should actually be given scope for profiling. “No one else can take our place, we have an important task,” says Gysi.

He intends to address the shortcomings, which he believes stand in the way of fulfilling this task, at the party conference, which is taking place in Erfurt at the end of next week. Then the party elects a new leader – and has to decide which direction to take in the future. Most recently, a dispute over how to deal with sexism in its own ranks had shaken Die Linke and led to the premature departure of one of the two party leaders.

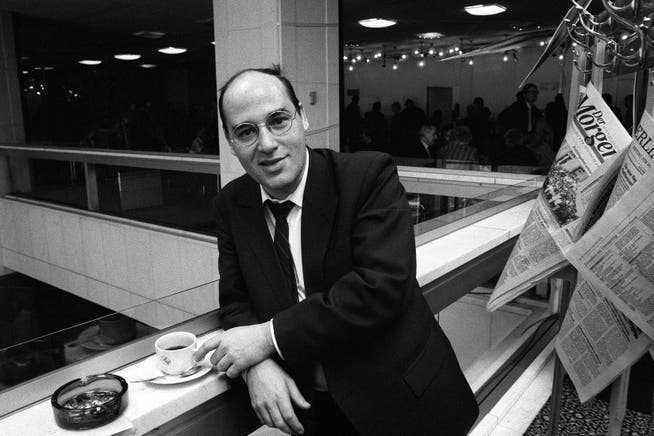

Gregor Gysi on April 5, 1990 on the fringes of the constitutive meeting of the People’s Chamber. On March 18, the GDR parliament was freely elected for the first and last time in its history.

“First of all, in public you can no longer distinguish between what is a minority opinion and what is a majority opinion in my party,” Gysi begins by listing the shortcomings. Secondly, there is a climate of denunciation that is unbearable. “Unbearable,” says Gysi, stressing every syllable. Anything negative you read about a member of the left comes from another member. And thirdly, the party has become “a shop for a thousand things”.

Gysi, who for some young left-wingers may belong in the category “old white man”, is of the opinion that his party is getting bogged down, for example with niche issues such as gender-equitable language: “We don’t have to deal with the colon, the capital ‘I’ and deal with the asterisk,” he says. “I don’t write anything I can’t speak.” It is not the language, but the circumstances that need to be changed “in the interests of women and diverse people”.

It is the well-known argument that has occupied and occasionally torn the political left across the West for several years: identity politics or core issues. Gysi wants his party to deal more with the latter again. From his point of view, these are peace politics, social justice, ecological sustainability and equality between women and men. “We have to make it clear which groups are most important to us: the workers.” For him, this also includes trainees and pensioners.

However, Gysi wants to cultivate a form of identity politics: His party should once again become the voice of the East. The left received just 10 percent in the last federal election in East Germany; four years earlier it had been 18 percent. The right-wing AfD achieved around 20 percent in the five eastern German states both times.

When asked whether those East Germans who still haven’t mentally arrived in the Federal Republic of Germany voted for the AfD anyway, Gysi replies pessimistically: “We won’t even be able to reach them anymore, they’re much too far away.” It would be better to woo SPD or Greens voters. That can be interpreted as a rejection of his party colleague Sahra Wagenknecht, who, like Gysi, is considered a critic of identity politics, but who repeatedly advocates theses that are otherwise heard from conservative or right-wing circles.

Equal pay for equal work

Gysi suspects that the lever to win back East German voters lies not least in employee rights. He sees a new spirit of resistance in eastern Germany. In the past, East Germans weren’t particularly fond of going on strike, but things are different now. There is a Siemens plant in Gysi’s constituency in East Berlin; in the western district of Charlottenburg too. “But with me you have to work three hours longer for the same wage.” Gysi also attributes the fact that this will soon no longer be the case to his commitment. “In such cases,” he says, “people turn to us, not to the AfD.”

What connects the Left Party and the AfD is, among other things, the transfiguration of Russia, which many of their voters and members are pursuing. “Of course, some who grew up in the GDR are very cautious when condemning Putin’s war of aggression,” Gysi admits. But young party members and those in the West sharply condemned the actions of the Russian president, “as it should be”.

The question of whether Germany is supplying enough weapons to Ukraine has occupied the German public since the Russian invasion at the end of February. Gysi is against German arms deliveries, at least on this point he agrees with the Russia friends in his party. “But we then have to compensate by paying for humanistic aid,” he says. “We shouldn’t be in a better position financially than other countries.”

Six days in Lviv, Kyiv and Bucha

Some opponents of German arms deliveries have the suspicion that they are not very interested in the fate of Ukraine. This is certainly not the case for Gysi: at the beginning of May he traveled the country together with Gerhard Trabert, a doctor who ran for the post of Federal President for the Left Party in February.

All other German and Western politicians who visited Kyiv went there and back on the same day, says Gysi. Trabert and he stayed for six days and visited Lviv, Kyiv and Bucha, among other places. “When we arrived in Lviv, the Russians greeted us with five rockets that fell not far from us,” reports Gysi. “But I wasn’t afraid.” The mayor of a Kiev suburb told him he needed tractors and concrete mixers. Gysi feels confirmed by the request: “So we can also deliver something other than weapons.”

Labor Day: the then PDS leader Gregor Gysi with comrades at the last May Day celebration in the history of the GDR (East Berlin 1990).

At the beginning of 1990, in the last months of the German workers’ and farmers’ state, when Gysi wanted to save his party for the first time, he answered the questions of the legendary interviewer Günter Gaus on GDR television. It was a serious, tense-looking Gysi sitting there in front of the camera, a far cry from the all-German talk show entertainer he was soon to become. In conclusion, Gaus asked what condition the Western system and the rest of the world would be in ten years from now, i.e. in the year 2000.

Then one would probably find oneself on the third way, Gysi replied at the time. By this he understood democratic socialism. “We’re still on the way there,” he explains 22 years later. “I always tell the left what capitalism can and cannot do: It can produce a highly efficient economy, research, art and culture at a high level. But he also earns money from wars and has great difficulties with justice and sustainability. »

Gysi now names the goal of preserving what capitalism can achieve and gradually changing and overcoming the rest. But first he has to get his party back on track. The troubles of the plain lie ahead of him, Bertolt Brecht would have said.