On foot, by bike, by public transport, by car or by train. What does French mobility look like? And what can they do fifteen minutes from home? On the occasion of European Mobility Week, “The World Cities” went out into the field to meet users and experts. Reports and investigations to be found in podcast and in writing in the series “A quarter of an hour in town”. Fourth episode of this dossier: the car.

In Saint-Quentin (Aisne), the bus subscription costs 33 euros per month while remaining free for the unemployed. Christophe (who did not wish to give his last name) could benefit from it if he did not live in Harly, the town next door. The Hauts-de-France region, in which he resides, grants a 75% reduction on train tickets to several categories of people, including “non-taxable job seekers who have exhausted their rights”, of which this 50-year-old is a part. But the steps are to be carried out online, an operation that puts him off.

Christophe does not have a car, and no longer has a driving licence. His wife has been hospitalized for several months in Guise, 30 kilometers from his home. To visit him, the Saint-Quentinois asks neighbors, or his parents, to drive him. For shopping, it’s on foot, at the neighborhood supermarket. But the big Auchan in Saint-Quentin is too far: you have to get on a bus then another, and the schedules are not coordinated.

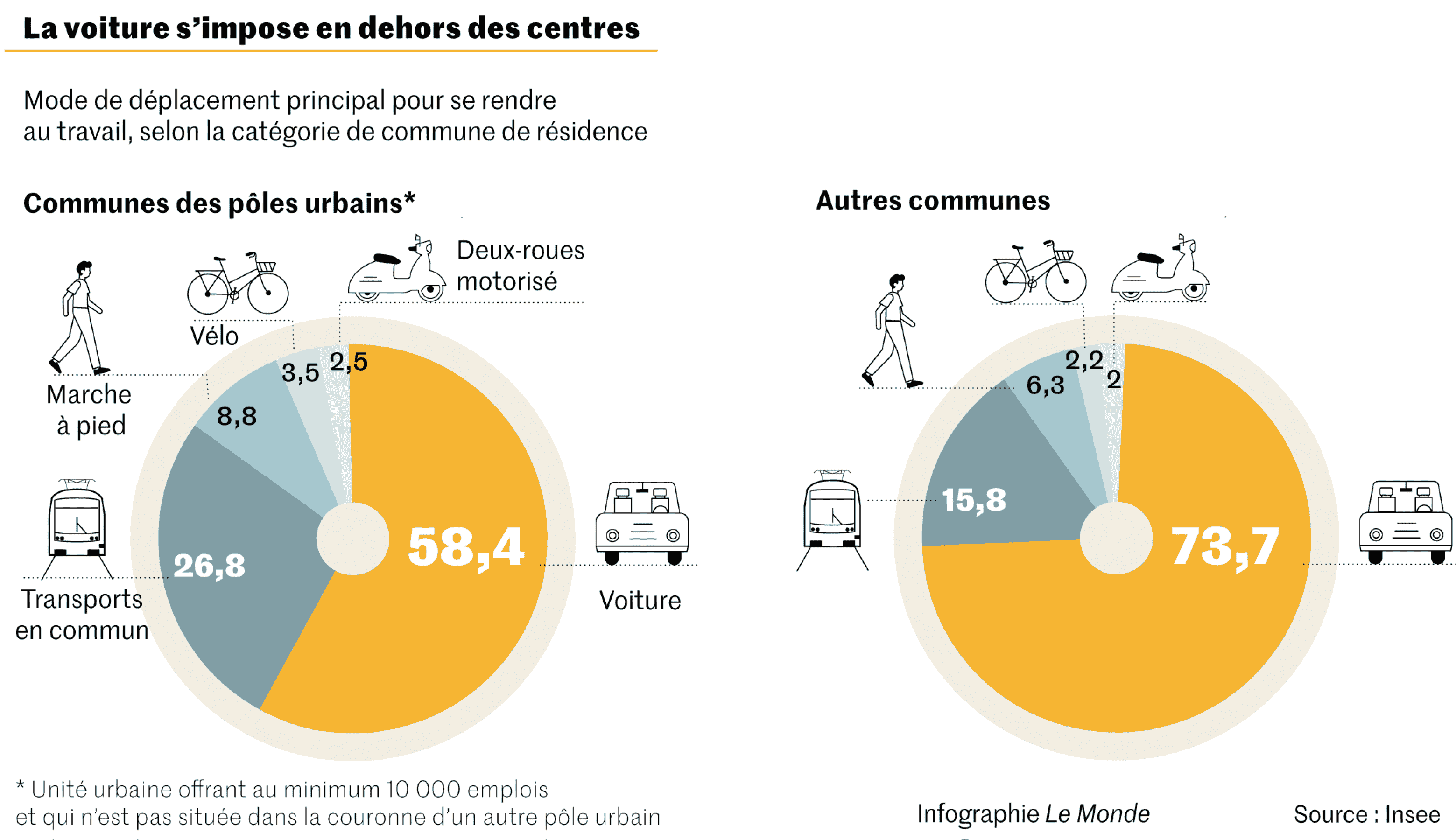

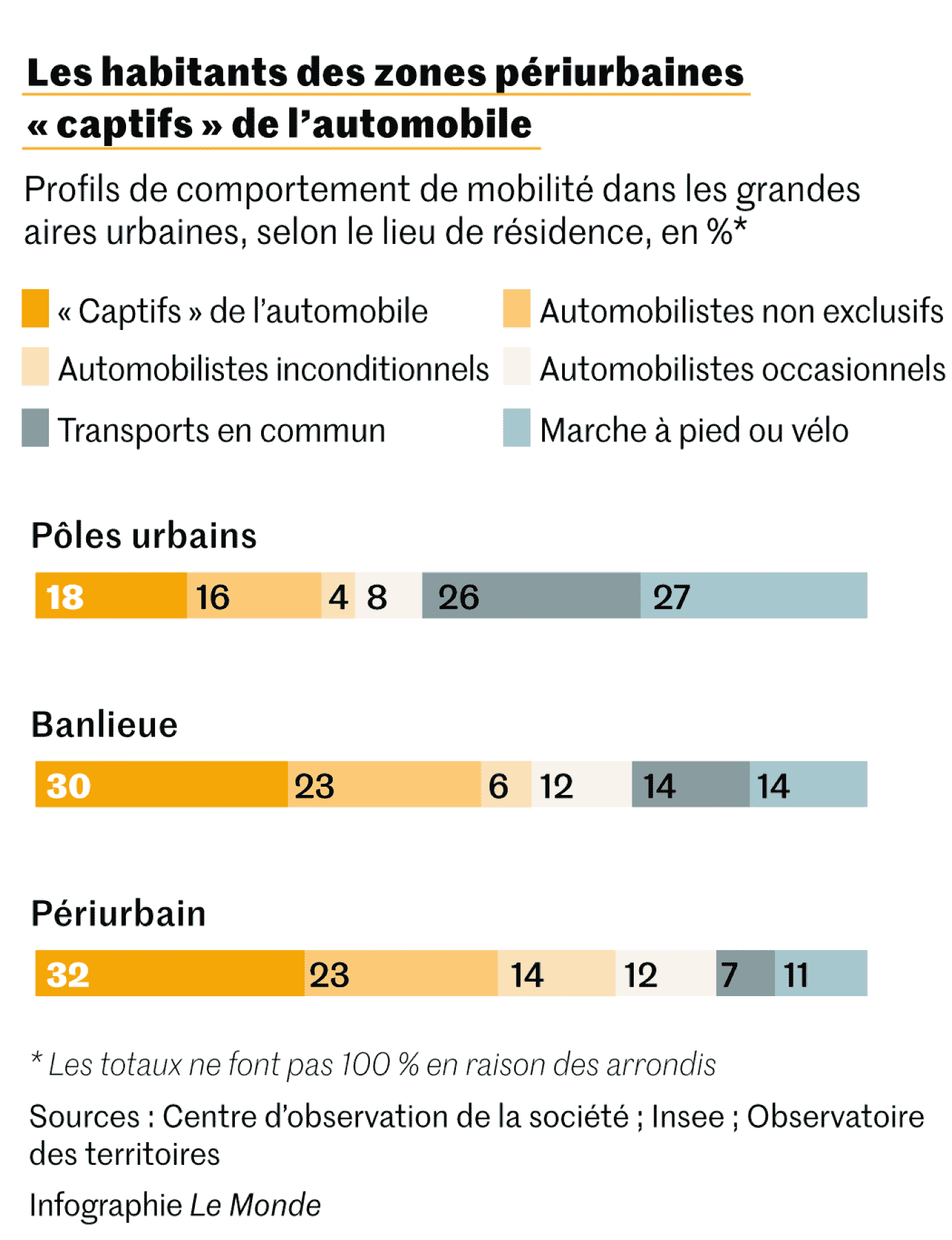

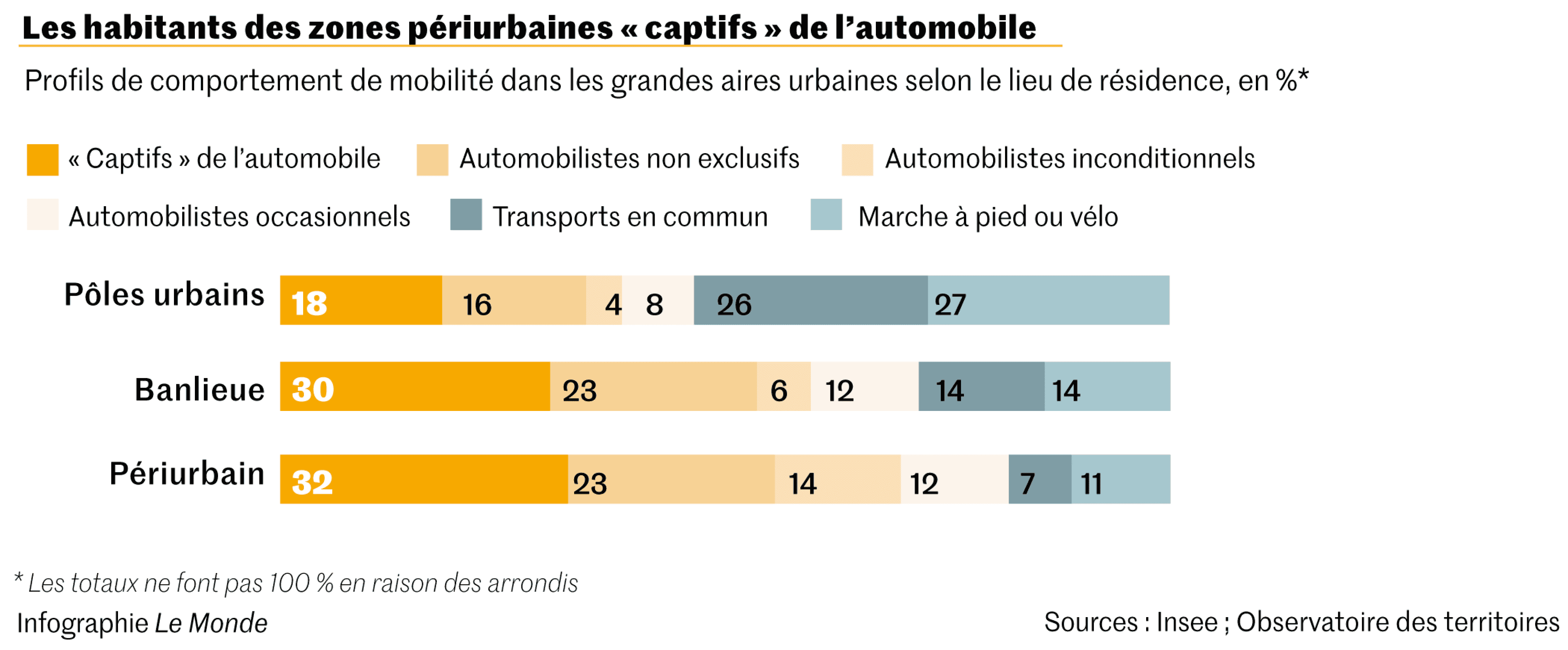

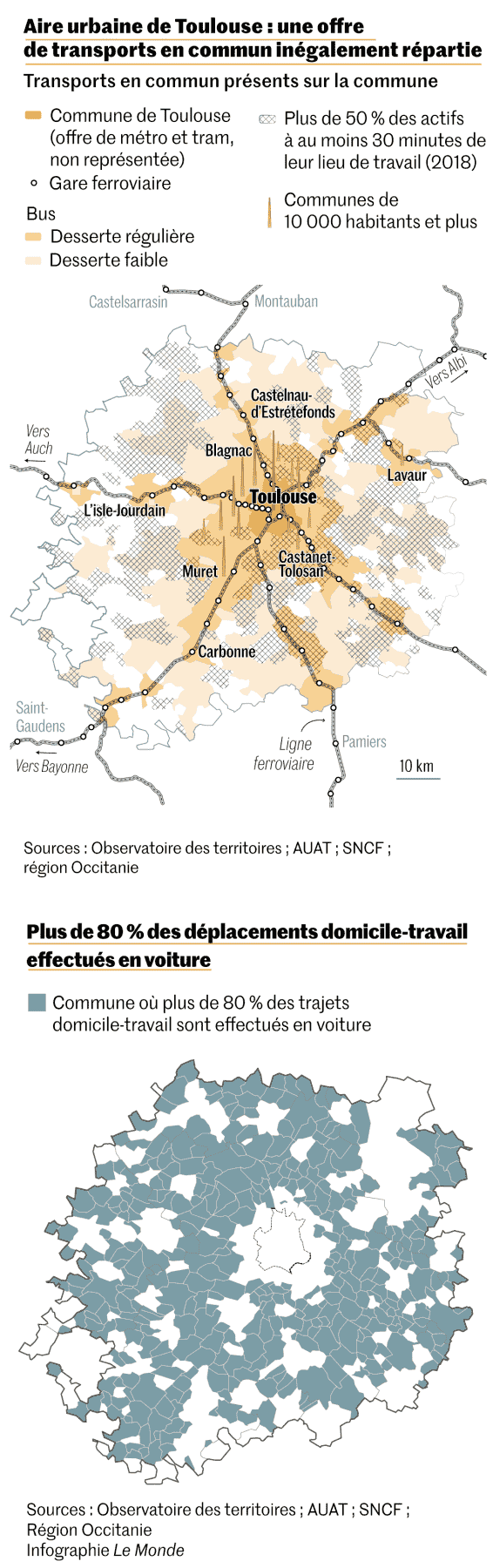

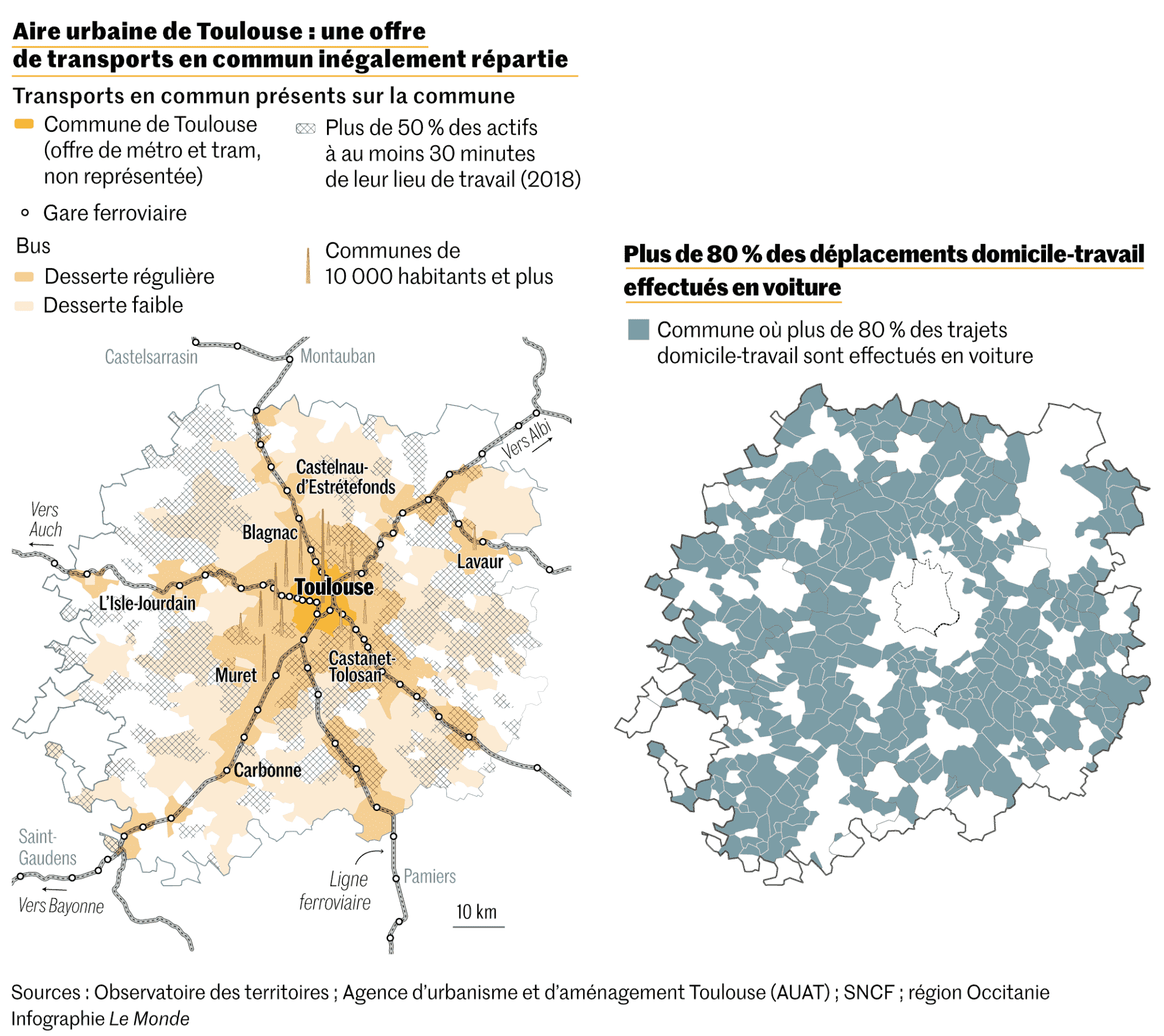

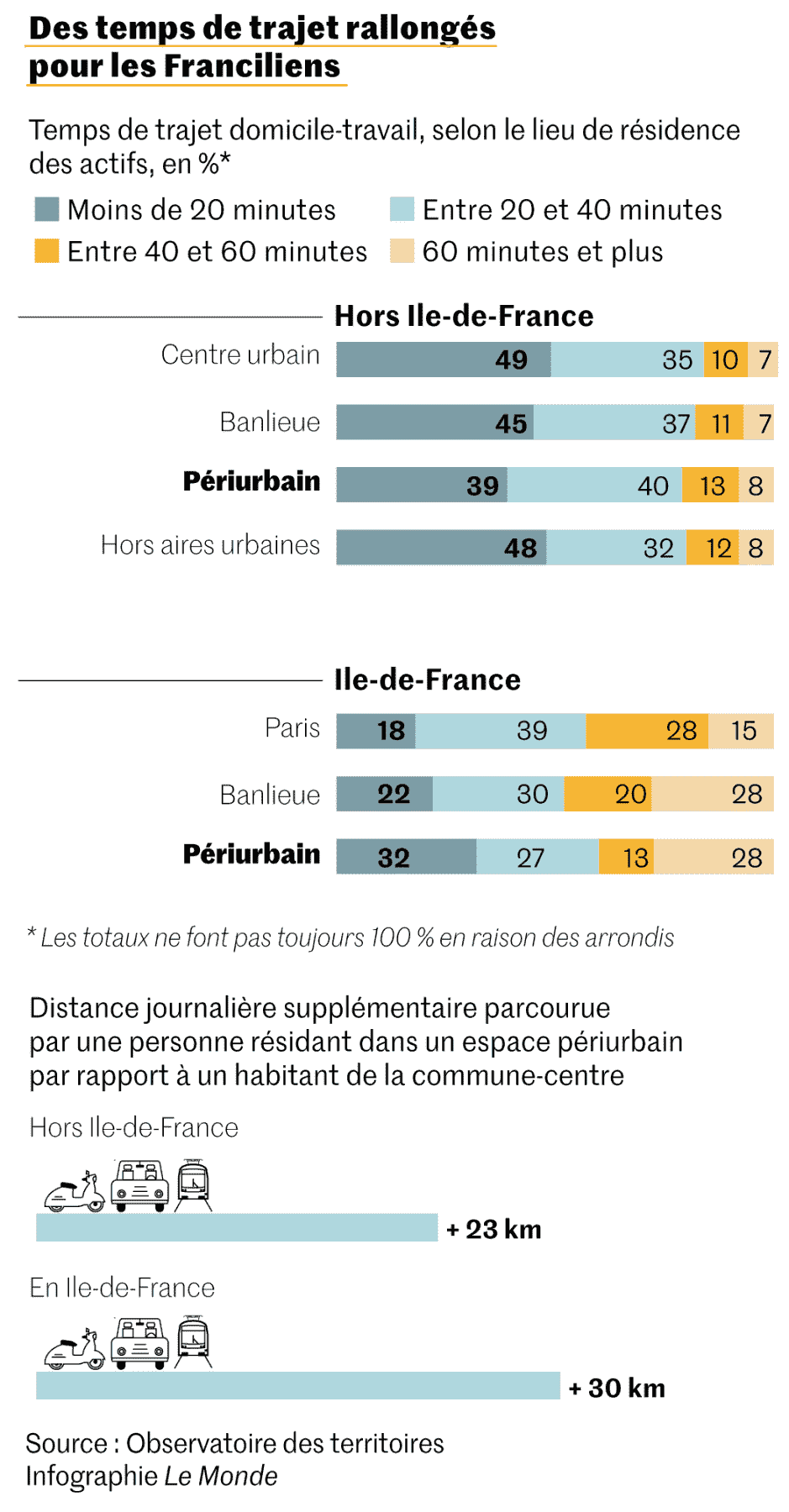

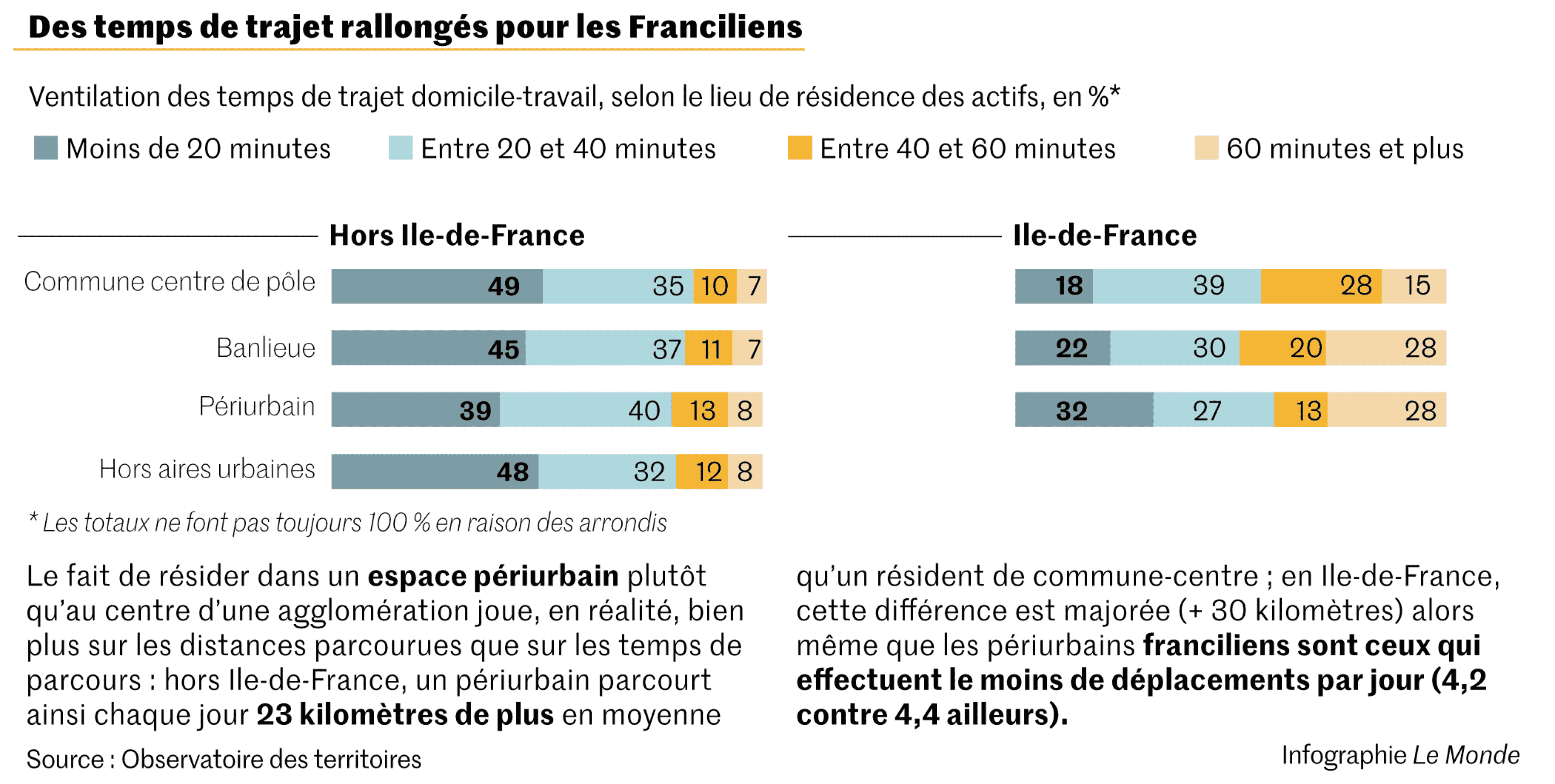

For Christophe, and so many other people living outside the big cities, the “quarter-hour city” model, in which all services are accessible within fifteen minutes, by bike or on foot, remains uncertain. In what is conventionally called peri-urban France, a string of small dormitory towns along a former national road, a housing estate far from a town center, the outer ring of a flourishing metropolis, we are far away. Far from urban centers. Far from their self-service scooters, their electric scooters, their flying taxis. And at the mercy of the vagaries of life, the engine failing, the employer moving the company’s premises, the intercity bus unexpectedly canceled.

Fatigue and mental load

This is the situation that users of the T86 bus in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region have been experiencing since April, which connects Allevard (Isère) to Grenoble in one hour. A fire damaged a bridge crossing the Isère, now closed to traffic. The route was diverted and the journey lengthened by thirty to forty minutes, depending on traffic jams. Katia Sandraz boarded this bus every morning to go to her job as a civil servant in Grenoble. Now she prefers to borrow “another bus passing Pontcharra, half an hour away by car. As there is no parking next to the stop, I have to add a six minute walk”, she testifies. A group of users, who had been demanding a reorganization of routes and timetables since the spring, obtained the addition of two direct buses in the morning and evening. Insufficient, they say. “We have the impression that the region is playing the strategy of small steps until the return to service of the bridge, scheduled for December”they testify.

Thus, the “peri-urban galley”, which in 2018 swelled the ranks of “yellow vests”, covers a diversity of situations which cannot be reduced to the question of the price of fuel. In a landscape dominated by suburban housing, designed by and for the automobile, the slightest glitch is paid for in euros, but also in time, fatigue, mental load.

Also, driving is not for everyone. According to the Keoscopie mobility observatory, powered by the carrier Keolis, 32% of drivers give up driving at night, 26% in rainy weather, while 30% seek to avoid having to make slots. Some of these intermittent motorists are elderly, but not all. In France, 18% of people over the age of 15 suffer from a long-term condition that limits their mobility.

Public transport, an “obstacle course”

To these personal difficulties is added the bad reputation of options other than the individual motorized vehicle, observes Michel Magniez, deputy for the environment of the mayor (LR) of Saint-Quentin. “Here, most of the discussions on mobility relate to the price of gasoline and the car, even though a third of the households in the town do not have one. Using public transport is seen as an obstacle course”regrets the chosen one.

In many medium-sized cities, buses do not run often, and even less so during school holidays

And for good reason. In many medium-sized cities, buses do not run often, and even less so during school holidays. Intercity bus timetables are sometimes difficult to consult, online or even at the stop, where they are printed on an A4 sheet slipped into a plastic bag that gets wet… The smartphone is not always the future mobility tool praised by transport operators. According to Keoscopie, only half of the population would be able to organize their journeys thanks to dedicated digital applications.

The mobility orientation law (LOM), adopted under the previous five-year term, tries to provide credible answers. The text authorizes, since 2021, “communities to subsidize carpooling trips”explains Julien Honnart, who created the Klaxit application in 2012. Thirty-five local authorities grant each driver an amount of 2 to 4 euros per trip.

The effects of the measure are already being felt. Between September 2021 and June 2022, the number of people transported increased from 159,000 to 408,000, according to the Carpooling Observatory, created by the State. Among the most active communities are “Rouen, Montpellier and Beauvais”indicates Julien Honnart, specifying, to cut short any bad trial, that, “Given the kilometers travelled, a carpooling trip financed by the community costs two to ten times less than if it were made by public transport”.

The job closer to bedtime

However, carpooling cannot solve everything, observes Laure Wagner, former manager of Blablacar, leader in the sector: “Between 1960 and 2018, the number of kilometers traveled by each person to go to work increased from 3 to 13 kilometers. The real problem is that we move too much! » In 2019, Laure Wagner founded 1 km on foot, to help employees bring their work closer to their home. “In sectors of activity as diverse as catering, personal services, security or retail, companies have several sites. And storekeepers, technicians, salespeople sometimes work far from home when there is an equivalent position nearby”she explains.

Thus, at Loxam, a professional equipment rental company with 11,000 employees, “74% of employees could work in an establishment closer to home. The average gain per employee reaches 11 kilometers morning and evening”, details the founder of 1 km on foot. These time savings make life easier for both employers and their employees, continues Laure Wagner: “People who work closer to home are absent less often and cultivate more friendly bonds with their colleagues”. The virtues of the rediscovered quarter of an hour.