A car garage in Rawalpindi, the twin city of the Pakistani capital Islamabad. On the first floor of the garage, three Afghans are crouching next to removed engines. They try to drive away the cold with a humming stove. One of them introduces himself as Amrullah. The mechanic does not want to give his last name. Because Amrullah lives illegally in Pakistan. Even though he was born here 34 years ago and is married to a Pakistani woman.

Legend:

Amrullah was born in Pakistan and married to a Pakistani woman. Nevertheless, his children are stateless.

SRF/Maren Peters

“Marriage didn’t give me any rights,” he says. And their four children are stateless. Since the Pakistani government announced last fall that it would deport all illegal immigrants, his family’s situation has deteriorated significantly, says Amrullah.

I don’t see a future for my children here. I don’t see any future for us at all.

The older children are no longer allowed to go to school. They could only rent a house with the help of a Pakistani. And he’s not allowed to work independently, even though he’s been there for so long. In addition, he and his children could expect to be deported at any time. “I’m disappointed and sad,” says the mechanic. “I don’t see a future for my children here. I don’t see any future for us at all.”

The government has been tightening the screws since October

That was not always so. Pakistan has tolerated Afghan refugees for decades. The first wave of refugees reached the country after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. After the Taliban came to power and the end of the republic in mid-August 2021, more than half a million Afghans fled to neighboring Pakistan.

We are afraid 24 hours a day that the police will come and take us away.

Back to the garage in Rawalpindi: an older Afghan man named Abdullah speaks out. His family fled to Pakistan decades ago because of a feud in Afghanistan. His family also no longer has valid papers. His own “Afghan Citizen Card,” which gave him a bit of protection, has expired. It will no longer be extended.

“We are afraid 24 hours a day that the police will come and take us away,” says Abdullah. “Every time our children knock on the door, we think they are coming for us.”

Bribes for the police

The only reason they haven’t been deported yet is because they regularly paid bribes to the police. “The police are only interested in money,” says Abdullah. Even Afghans who still have valid documents would have to pay regularly. He also knows of cases in which the police even destroyed valid residence permits just to collect money. Anyone who doesn’t pay will be deported. Many fathers who would be deported without their families tried to re-enter via Iran or other countries. But that is very expensive.

They could feel safe until the Pakistani government suddenly announced on October 3 that all illegal, undocumented refugees would have to leave the country within a month. Otherwise they would be deported. This primarily affected 1.7 million illegal Afghans. The government blames them for a series of terrorist attacks in Pakistan. And by expelling the refugees, he presumably wants to put pressure on Afghanistan to take part in solving the terror problem.

His compatriots also confirm that money plays a key role. The police always ask for money, says mechanic Amrullah. They wanted up to 40,000 Pakistani rupees per visit, the equivalent of 125 francs.

It is unfair to condemn all Afghans across the board because some are said to have been involved in terrorist attacks.

Until now, they had always paid – even if they barely had enough money to live on. Because returning to Afghanistan under the Taliban would be too risky for his family, says Abdullah. His sons served in the Afghan military before the Taliban came to power. If they returned now, the Taliban would most likely kill them.

UN criticizes the deportations

In a hotel in the capital Islamabad, Qaiser Khan Afridi takes time for a conversation. He is spokesman for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Pakistan. The United Nations has called on Pakistan not to expel Afghan refugees.

Legend:

According to UNHCR, half a million people have already returned to Afghanistan. Images from the Torkham border crossing between Pakistan and Afghanistan (October 30, 2023).

The Norwegian Refugee Council/Handout via REUTERS

“It is unfair to condemn all Afghans across the board because some are said to have been involved in terrorist attacks,” says Afridi. In addition, the humanitarian situation in Afghanistan is difficult. The cold winter, the consequences of the earthquakes, all make it difficult to return. But the Pakistani government only promised the UN that it would not send the risky cases back. These include, for example, former government employees or members of the military under the old regime, before the Taliban took over in August 2021.

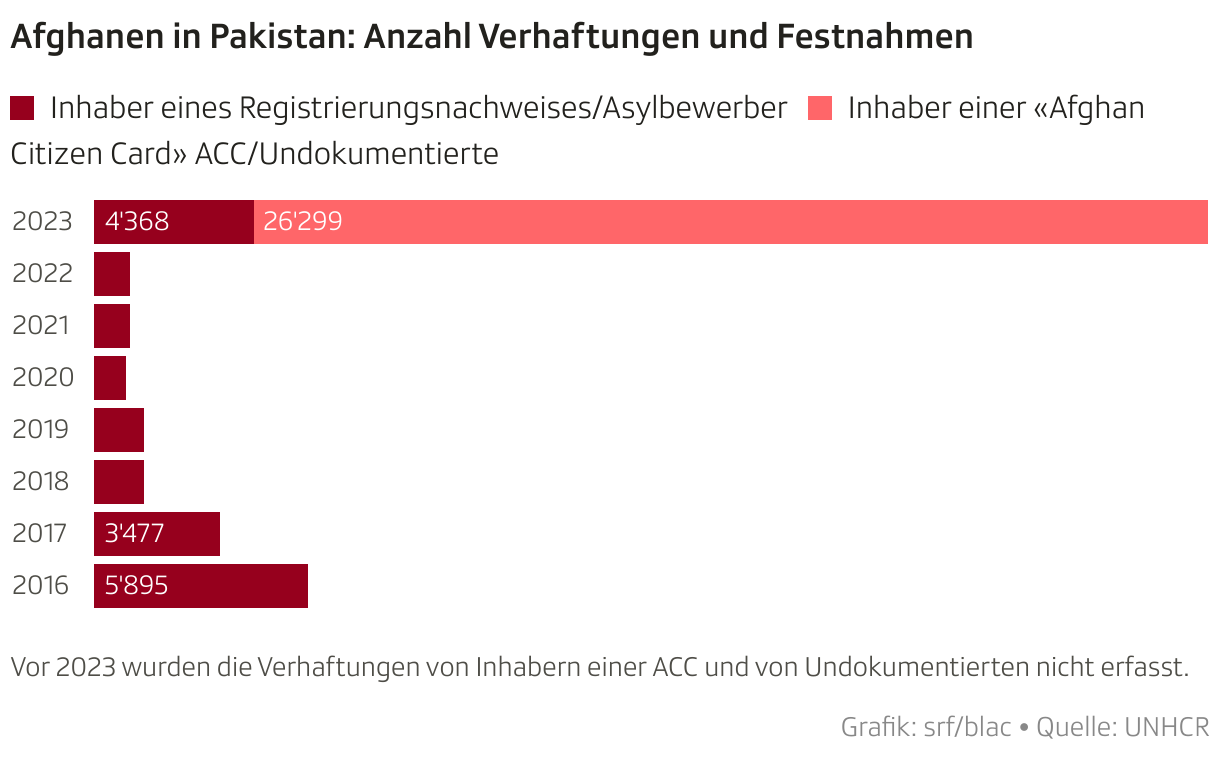

And yet: “There have been some unpleasant incidents,” says Afridi. The Pakistani police have even threatened, arrested and deported registered Afghans. The UN authorities can only help very few refugees.

Huria’s family pins their hopes on the UN

Huria also hopes for that. She lives with her family in purely Afghan quarters in Islamabad. The visas have expired, they are illegals. The family fled to Islamabad after the Taliban came to power. One brother was killed by the Taliban, the other worked for the old government, says Huria. Therefore they could not go back.

The family lives in a simple house with other refugees. Cooking takes place in front of the door. They would also have to expect deportation at any time. “Someone is always sneaking around the house,” says the 21-year-old. Their last straw is the UN refugee agency. Her brother has already conducted two interviews and is now waiting for the crucial third interview, says Huria. The family is hoping for residency papers in Pakistan. They no longer had any other option.