The Federal Republic is at the limits of its absorption capacity. Municipalities in particular are complaining. The federal government is exacerbating the problem with false incentives and additional admission programs.

Germany is finding it increasingly difficult to accommodate migrants.

Germany’s municipalities are at the limit. More and more districts, towns and communities are at a loss when it comes to accommodating refugees and asylum seekers. Some even hoist the white flag. The district administrator of the Saxon district of Bautzen recently asked the state’s interior minister to stop admissions. The district sees itself unable to take in more refugees.

In Berlin, the Senate erects tent cities and sets up containers. In other cities, due to a lack of alternatives, gymnasiums have to be used, which are then no longer available to the population. Local politicians actually want to avoid such competitive situations between citizens and refugees at all costs, so as not to strain acceptance among the population.

The situation is not the same everywhere. According to the Integration media service, large cities such as Berlin and Hamburg are particularly under pressure. The occupancy rate of the accommodations there is almost 100 percent. In Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Lower Saxony, two out of ten places are still available on average. Nevertheless, the challenges are enormous. And they could still increase. Berlin’s Secretary of State for the Interior, Torsten Akmann, even expects another million Ukrainian refugees to come to Germany in view of the winter.

Over a million refugees from Ukraine

In this year alone, the Federal Republic has already taken in more people than at the peak of the asylum crisis in 2015 and 2016. At that time, a total of 1.187 million people were registered. Up to and including October this year this number has already been exceeded by 20,000 entries. War refugees from Ukraine make up the majority.

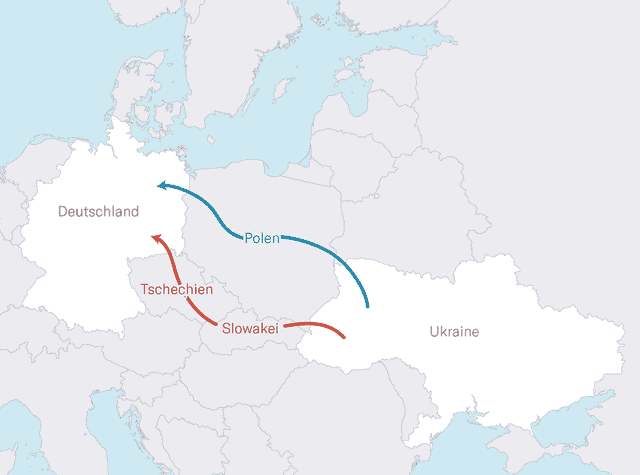

According to the German authorities, more than 1.021 million Ukrainians were registered in mid-November. A third are minors. The majority of adults – 70 percent – are women. A small number, it is said, could have traveled to other EU countries or back home. The number of new refugees arriving from Ukraine has also recently decreased.

There are also asylum seekers from all over the world. According to the authorities, 181,612 people applied for asylum in Germany between January and October inclusive. That was almost 20 percent more than in the previous year during this period. In the case of initial applications, there was even an increase of almost 40 percent. The majority of non-Ukrainian migrants come from Syria, followed by Afghans, Turks and Iraqis. Due to the difficult economic situation and the galloping inflation, many Syrians do not want to or cannot stay in Turkey, but neither do they return to their homeland and make their way to Europe. Many Turks are also trying to gain a foothold elsewhere.

Ukrainians have different status than asylum seekers

The legal status of Ukrainians differs from that of other migrants. You can enter the EU without a visa and enjoy temporary protection. You must be registered in Germany within 90 days. They do not need to go through an asylum procedure. In contrast to asylum seekers, they do not receive any benefits under the Asylum Seekers Benefits Act, but have been integrated into the regular social assistance system since June. They are also allowed to work and have access to statutory health insurance. Refugee organizations have criticized this as a two-tier system.

Unlike in 2015/16, when Angela Merkel’s opening of the border breathed new life into the struggling AfD, the admission of Ukrainians in Germany is not politically controversial today. Even the migration-critical AfD does not question them. It is too obvious that the people of the attacked country need the solidarity of their neighbors. However, there is criticism from the opposition that the federal government is further exacerbating the problem.

“This federal government has learned nothing from 2015 and is deliberately pursuing a failed admissions policy,” says Bavaria’s Interior Minister Joachim Herrmann of the NZZ. The Christian Social is particularly critical of the fact that the federal government decided on new admission programs for 40,000 Afghans without consulting the federal states. In fact, in addition to the local staff working for Germany during the Afghanistan mission, thousands of women’s rights activists, journalists and other people threatened by the Taliban regime are to be brought to Germany every month.

Illegal migration has increased

Representing the criticism from the Union, Herrmann also complains about the ineffective border protection. “We want to take in war refugees from Ukraine. We must limit the influx of other refugees all the more. This requires better protection of the EU’s external borders,” he says. In October, the Federal Minister of the Interior, Nancy Faeser, announced that controls at the German border with Austria would be extended. However, because the country refrains from being rejected at its borders, anyone who has made it onto German soil can still apply for asylum in Germany. And Germany is obliged to examine every asylum application.

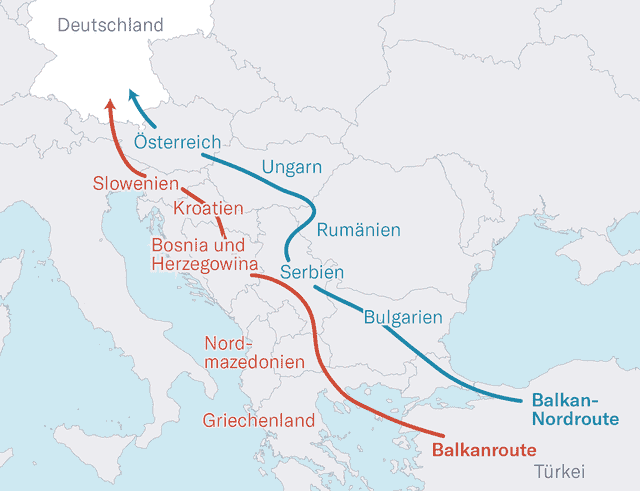

It has been clear for months that illegal migration on the Balkan route has increased sharply compared to the previous year. The federal government already had corresponding figures from the EU border protection agency Frontex in the summer. One of the reasons, in addition to the elimination of corona-related travel restrictions, is that Poland has stopped the temporarily strong migration via Belarus. A shift back to overland routes has taken place in south-eastern Europe.

In addition, the so-called refugee deal with Turkey, which as the country of origin of the route should make a significant contribution to controlling migration, is apparently working less well. Serbia had also – much to the annoyance of the EU and Switzerland – exempted citizens of states that support its Kosovo policy from the visa requirement. Numerous Tunisians, for example, set off for this reason.

In the meantime, a good number of these people have arrived in Germany after having passed through a series of safe countries, including those within the EU. Bavaria, which is at the end of the route, is particularly affected. The Federal Police recently counted over 70,000 illegal migrants throughout Germany. This emerges from a response from the federal government to a request from the AfD parliamentary group.

This means people who do not have an entry permit for Germany. The dark number of illegal entries is of course higher. One way or another, most then apply for asylum and end up in the official asylum statistics. The chances of successfully completing the procedure vary depending on the country of origin. However, there are numerous possibilities for objection before a rejection. And rejection does not mean deportation.

Because for years Germany has not been able to deport a significant number of asylum seekers who have ultimately been rejected and are only tolerated to their countries of origin. In its coalition agreement, the Ampel government set itself the goal of a “repatriation offensive” in 2021. This consisted in evicting criminals and menaces in particular. So far, however, there have been no resounding successes. Unclear identities and countries of origin unwilling to take them back are usually the reason. In the first half of 2022, 6,198 foreigners who were required to leave the country were taken out of the country, an increase of 9 percent compared to the same period in the previous year. But that’s hardly a trend reversal.

Anyone who makes it to Germany can stay

This confirms the impression that those who have only made it to Germany need hardly fear having to leave the country again. And the fact that many migrants end up in Germany despite having passed through several EU countries naturally has to do with the high level of benefits for asylum seekers, even by European standards.

Politicians from the CDU, CSU and AfD also fear that the federal government will provide further incentives for illegal migration through social policy projects. In addition to the citizen income, which will be largely free of sanctions in the first few months, the so-called right of residence is also to come into force on January 1, 2023. Tolerated foreigners who have lived in Germany for more than five years without being punished should be able to prove for a year that they can take care of themselves. Otherwise they fall back into the Duldung. Critics complain that mixing asylum and work migration creates an additional false incentive.

Even years after the great migration crisis of 2015/16, Germany is still a long way from a functioning asylum and migration policy.