While the gas crisis has Germany firmly in its grip, Feldheim in Brandenburg is hardly affected by the high energy prices. Because the small town has been supplying itself with electricity and heat for years. This is made possible by a well thought-out system with exemplary character.

Dozens of wind turbines tower high in the cloudless sky out of the seemingly endless fields of corn and rye. Gently circling rotor blades form the backdrop of the small village of Feldheim, which at first glance does not differ from the countless sleepy towns in the Brandenburg province. Older residential buildings are lined up along the only thoroughfare. In the shade of the deciduous trees, the weather gnaws at the wood of the barns. You won’t find any supermarkets, bakeries or restaurants here, around 90 kilometers south of Berlin.

Doreen Raschemann is chairwoman of the Förderverein Neue Energien Forum Feldheim.

(Photo: Robert Greenness)

What distinguishes the people in Feldheim from many others: They can look at the energy crisis with equanimity. While skyrocketing costs are threatening livelihoods in the rest of the country and gas storage levels depend on the whims of Russian President Vladimir Putin, the village of 130 has been providing itself with electricity and heat for over a decade. A clever interaction of renewable energies and its own electricity and heating network make Feldheim the first and only completely energy self-sufficient place in Germany.

It’s paying off: “While prices are rising everywhere, our electricity is even cheaper than ever since the EEG surcharge was dropped in July,” says Doreen Raschemann from the New Energies Forum Feldheim, not without pride. In the modern visitor and exhibition center, she welcomes guests from all over the world who want to learn how the energy transition can be implemented fairly and functionally.

Feldheim offers location advantages

It all started in the early 1990s with her husband’s idea. Doreen Raschemann remembers: “Michael was still a student at the time and had it in his head to build wind turbines. So we rummaged through maps for the locations of old windmills – and came across Feldheim.” Located on a high plateau in the Hoher Fläming country park, the area offers sufficient space and, above all, a lot of wind – the best conditions.

“People initially had a classic need for information and were also skeptical about the construction of wind turbines,” says Michael Knape in an interview with ntv.de. The mayor of the town of Treuenbrietzen, to which Feldheim belongs, has supported the project from the start. “It was about distances to the village, how loud the systems are and whether too much area would be left for agriculture.” However, there was a healthy basis for discussion, says Knape. “The discussion was never controversial, but always aimed at dialogue. That’s how compromises came about again and again.”

A private individual finally leased land to Raschemann, and the local agricultural cooperative agreed. Then everything happened very quickly: in 1995 his newly founded company Energiequelle GmbH put the first wind turbine into operation. In the meantime, an entire wind farm has grown, and the 55 wheels now feed 250 million kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity into the public grid every year. For comparison: one million kWh would be enough to supply all of Feldheim with electricity for a year.

In addition, in 2008 an abandoned military site in the area was converted into a solar park by Energiequelle GmbH, on which almost 10,000 photovoltaic systems convert the sun’s rays into energy. They cover the annual needs of around 600 four-person households. All this is progressive, but not yet unusual. Rural areas in Germany act as a driver of the energy transition, onshore wind turbines characterize the image of entire regions.

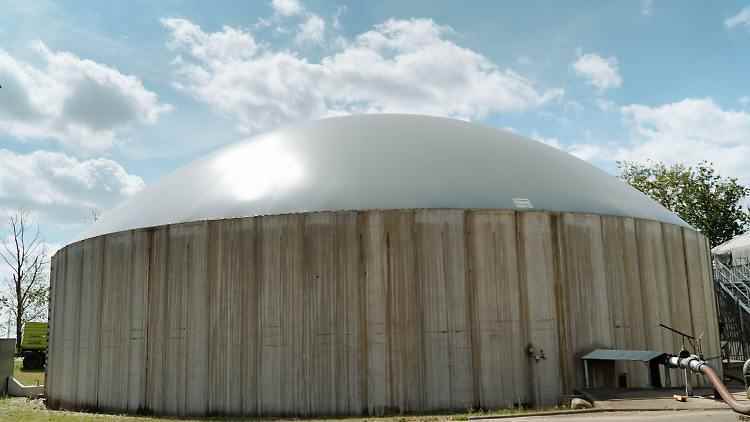

Not only own electricity, but also heat

In Feldheim, on the other hand, there was enough trust in the pioneer Raschemann and his company to go one step further. Together with the agricultural cooperative, the plan came about to produce heat on site in addition to electricity. Since 2008, they have been supplying a biogas plant with an integrated combined heat and power plant. The mixture of liquid manure, maize silage and crushed grain needed to generate energy comes from the local farmers. The plant is operated by the agricultural cooperative, now the largest employer in Feldheim with 30 employees. When the heating is running at maximum output on particularly cold winter days, a wood chip heating system is switched on. The burning of shredded wood from the surrounding forests then ensures additional safety in heat production.

Initially, the biogas plant was only intended for commercial use, but interest also arose in private households. In order for a connection to be economically worthwhile, however, a separate local heating network was required. “First, we determined the heat requirement in Feldheim. After three citizens’ meetings, it was clear to almost everyone: It’s worth it,” says Raschemann. Because heating via the biogas plant not only saves maintenance, but above all expensive heating oil – and also CO2. The villagers got together and founded their own energy supplier, Feldheim Energie GmbH & Co. KG. “Suddenly the Feldheimers were entrepreneurs and had their own municipal utility,” she recalls.

A veritable desire for independence was awakened. The thought: If the street has to be torn open anyway to lay the lines, why not feed the electricity that is produced on the doorstep into a separate network?

“It wasn’t the plan from the beginning to make Feldheim self-sufficient. But in the end it was only logical to put the many different building blocks together and build up a secure supply,” says Mayor Knape. “This could only be implemented in a trusting partnership between Energiequelle GmbH, the local agricultural cooperative Feldheim eG, citizens and the municipality, which developed together over many years. There was no experience with this in Germany.”

The plan to buy the power lines from the operator Eon Edis previously failed due to resistance from the group. From a business point of view, self-sufficiency has little added value, it means a loss of customers and money. So the people from Feldheim tackled it themselves. With the exception of two, all households in the village took part with 3,000 euros of their own the remainder of the 1.7 million euro project was funded by the EU and the state of Brandenburg. Feldheim has been completely self-sufficient since 2010.

“We are very proud”

Nevertheless, there was still skepticism at the beginning. The local waterworks, for example, initially did not connect to the Feldheim power grid – the safety concerns were too great. “When there was a power failure in the region and everything was gloomy except for Feldheim, the waterworks changed their minds,” says Raschemann. Since then there has not been a failure. Today, 34 households, including five businesses, are connected to the grid. “A project like this can only be realized through cooperation. We’re very proud of that,” says Raschemann.

At the time of commissioning, the battery storage was the largest in Europe.

(Photo: Robert Greenness)

For school classes, politicians and delegates, whom Raschemann regularly guides through the village, the individual pieces of the puzzle of the ingenious overall concept open up away from the main street. The battery storage system, which was switched on in 2015 and was the largest in Europe at the time, is brightly painted in the vicinity of a pigsty. The power plant regulates the electricity and ensures the supply even when there is a lull and there is no sun.

With all their independence, the people of Feldheim naturally also feel inflation. High fuel prices would be a burden for many, says Raschemann, because nothing works here without a car. The bus only stops six times a day at the bus stop that is lost on the side of the road, before continuing on to the district town of Treuenbrietzen. Symptomatic of the province, people are dependent on local public transport.

Nevertheless, Feldheim is more than a step ahead of the rest of Germany, especially in times of crisis. At 12 cents per kWh, the electricity price is only around a third of the current average. The heat costs 7.5 cents per kWh, market fluctuations are irrelevant. The energy from the biogas plant and wind farm is passed on to the connected consumers at cost price.

It’s not about self-sufficiency

Even if it gives the impression that Feldheim does not want to be a Gallic village. “It’s not about self-sufficiency, that is, that we are happy here and everything around us falls together. It’s about decentralization,” Knape clarifies. For decades, a central energy supply was the mantra in Germany. “But renewables can only be generated decentrally.” Therefore, the supply derived from this should also adapt to these decentralized ideas. “Perhaps one day many small Feldheims will even be able to supply Berlin.”

The fuel required for the wood chip heating comes from the surrounding area.

(Photo: Robert Greenness)

According to Knape, however, there is a lack of clear political will to drive change and really rethink the energy supply in Germany. Instead of promoting spaces for experimentation and allowing a pioneering spirit, decision-makers are often stuck in outdated structures. “With the rules of the past, it’s difficult to provide answers for new approaches,” says Knape. “But we in Feldheim have been proving for over ten years that decentralized generation and supply based on renewable energies is also possible from an economic point of view.”

“What can work on a small scale also works on a large scale,” believes Raschemann. Of course, not every place can set up its own supply network. That wouldn’t even make sense. But Feldheim shows how visionary ideas, open-minded politics and the solidarity of committed citizens can make a difference – and make a contribution to climate protection.

“Everyone involved will benefit from the energy self-sufficient village project,” according to Raschemann, that’s Feldheim’s recipe for success. Through the lenses of her sunglasses, she scrutinizes the wind turbines rising above the tiled roofs, briefly instructing them on the phone which systems a technician still has to visit today. In Feldheim, energy security is not an abstract, politically charged concept, but a living practice. The people here are only dependent on what surrounds them. This gives them the certainty that they will also be supplied with sufficient energy tomorrow.