Some call him “Grand-papa”, for others he remains the “Père”, for others the idol par excellence. Roger Milla, now 70, personifies the revival of African football and is not only well known in Cameroon. A visit to him in the Cameroonian capital Yaoundé.

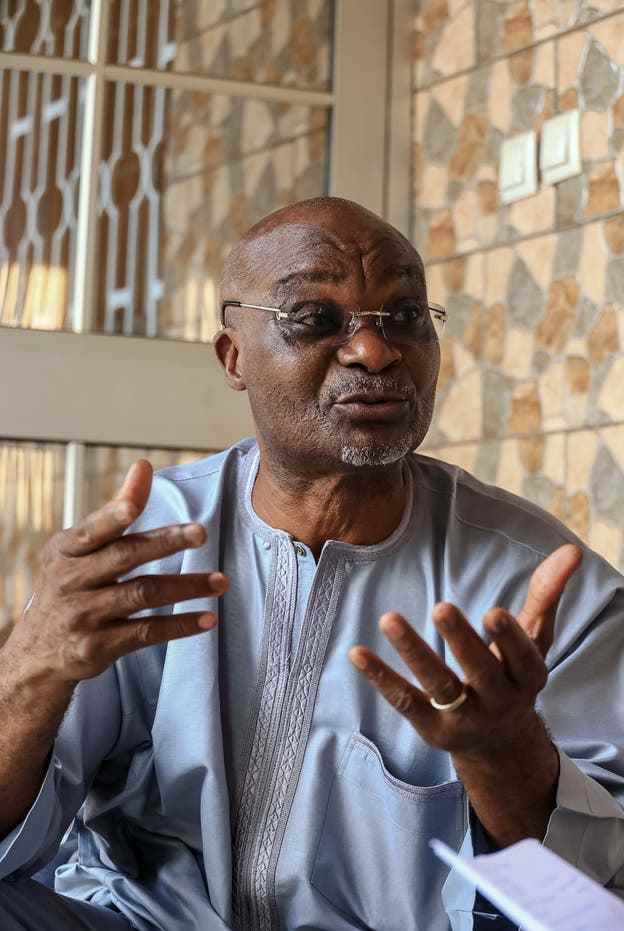

An oasis in the Cameroonian capital: Ambassador Roger Milla in the garden of his villa in Yaoundé at the end of October.

Living the comfortable life of ministerial rank, he is an ambassador to Cameroon, still idolized and present in the stands of local football stadiums. Roger Milla, now 70, is leading the revival of African football on the international stage. World Cup 1990 in Italy, Cameroon advances to World Cup quarterfinals, 4 goals from the 38-year-old forward dancing at the corner flag. Pictures for eternity.

The security guards open the gate in front of the Milla villa in Yaoundé. While African activity can be seen a few meters away at a crossroads with bumpy sand tracks, one feels like in an oasis here. The gardeners are at work, the sun is shining, the birds are whistling. Milla comes after 45 minutes. He shakes hands and says in greeting: «You actually know me? Where from?” A joke to loosen up.

Monsieur Milla, you are not an icon in Cameroon, you are the icon. Tell us why.

I do not know. Not even the journalists call me an icon. It’s the people, the fans, the fan clubs.

We need to talk about the 1990 World Cup.

Yes, too, but that started with the 1982 World Cup, when we took part in the World Cup for the first time.

But the images of Roger Milla that stick in Europe are the goals and dancing at the corner flag outside.

Yes, in Europe. Africa already knew me back then.

In addition, you were 38 years old in 1990 and 42 in the USA in 1994. You are still the oldest goalscorer at the World Cup.

Voila. You don’t have to ask the icon. I’m a legend, a living legend.

What does the 1990 World Cup symbolize for Cameroon?

That’s when the history of Africa, related to football, began. Of course, this story had happened before, Africans had played in Europe. But no team had reached this level before. 1990 represents the discovery and advancement of African football.

1990 World Cup in Italy: the great goal and dance show by the then 38-year-old Roger Milla.

You weren’t there during the preparations for the World Cup and then only substitute players at the World Cup. Why?

I retired from the national team in 1988 and lived on La Réunion. When I came to Cameroon for an anniversary game, things went well – and I was begged by spectators and former team-mates to return to the selection. Thus the idea of returning was born.

Soon you received a call from Paul Biya. He was then President of Cameroon and still is today.

Yes, he heard the voices. He told me to accompany the team. You can’t refuse a request from the President. He is like a father to us.

Does such political intervention occur frequently?

Hardly in this way. We’ve made a change in Cameroonian football. Now Samuel Eto’o is President of the Football Association. He was a great player who received a lot from football. Now he wants to give something back. Before him, Cameroonian football was in a crisis, but things are going better now. The stadiums are filling up. A line can be seen.

The start of the World Cup high in 1990: Cameroon, with Roger Milla coming on as a substitute in the 81st minute, defeated Argentina and Diego Maradona 1-0.

The Cameroonians celebrate Milla’s second goal against Colombia in the 1990 World Cup round of 16 and win 2-1 in the end.

Where do you see the merits of African football?

The difference between the domestic leagues and Europe, where many Africans play, is big. Physically we’re better, technically we’re the same, but in terms of tactics and organization we’re lacking. We still have a lot to do in African football.

It has been said for years that African football is politicized.

Yes, football is also politics. It’s important, like a government job. The sports minister is heavily involved in Cameroon, sometimes making decisions. With Eto’o, however, the political influence is likely to decrease.

African selections are often accompanied by arguments over prizes at tournaments. Why is that?

Yes, but what about Europe? It’s often about money, too. That’s normal, isn’t it? The players demand bonuses, in Africa as in Europe.

In 2006, World Cup participant Togo tripped up on himself. The bickering over bonuses resulted in the threat of a strike.

Yes, but we have that under control. There are no more discussions. Eto’o was a footballer. He knows what needs to be done, what the role of the association is and what the role of the players is. I have faith in Eto’o. Football has changed. When I was a player, Eto’o was just a kid. Eto’o looks for minimum wages in the Cameroonian league. When people do good things, you have to acknowledge that. And you have to say it.

How much did you earn as a footballer back then?

You can’t compare that to today. I had nothing. Today I would earn more and might be one of the richest Cameroonians. I came to Europe when I was 25. That was late. I started in France at Valenciennes, a small club.

How did the connection between you and Valenciennes come about?

A Cameroonian had married a woman from Valenciennes. He often came back here on vacation, saw me play and asked himself: Why doesn’t he play in Europe?

How difficult was the beginning?

The leap was big. I got used to it with a little delay. But when I later played for Monaco, I was already 28. There wasn’t that much time left.

You turned 70 in May. You seem to be in good shape.

Well, I’ve got a good job and I’m constantly with doctors and medical professionals. If I have foot or back pain, I can go to the doctor.

Don’t you play football anymore?

It’s over. I scored my last goal on May 20, 2022 in Yaoundé, on my 70th birthday. We hosted a match against some friends.

Was your last goal nice?

The cross came in and I put my foot out. instep. Goal.

And then the dance?

Naturally.

Roger Milla.

Roger Milla.

Paintings depicting the former Cameroonian international can also be seen in the garden of Villa Roger Millas.

A question for the experts: Cameroon was in the World Cup quarter-finals in 1990, Senegal in 2002 and Ghana in 2010. Otherwise, the Africans usually go home after the World Cup group stage. Why?

Africa must have nine World Cup participants, four more than today. Then we would have better results.

But that doesn’t solve the sporting problems.

We are entitled to more starting places. Big nations like Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Nigeria and Algeria are not there this time. We are the largest continent and only have five World Cup participants.

Would that improve the results?

Aren’t there any Europeans going home after three games? They only talk about Africa, alas. And the South Americans?

How far is Cameroon in the World Cup?

We’ll do it as usual: beat Switzerland in the first game, then it’s on. We can worship the Lord – and reach the semifinals. We have strong faith.

When asked if Cameroon would win in Qatar, Samuel Eto’o replied: “May God hear us.”

Voila.