Is the Freebox Ultra really eco-friendly? © Free

“It was a desire of the Free teams from its conception […] Making the Freebox Ultra a sustainable, eco-responsible product.” In a wooden setting, Free took four minutes during its launch conference to detail how the company plans “do better and have a real positive impact” on ecology with its Freebox Ultra. Xavier Niel also repeated it shortly after on the set of C to you.

In its communication, Free touches on many subjects to try to explain how its new box is “particularly responsible”. Let’s see the operator’s promises and their concrete impacts.

Consumption: a misleading indicator

First argument deployed by Free, that of electricity consumption. The new high-end Freebox would consume “as little as the smallest box on the market”, or 9.9 W, as much as the Freebox Pop. The Ultra also promises 95% energy savings with its new Total Sleep mode.

You will have to check these figures once you have the box, but we can say that this figure of 9.9 W is only valid when the Eco Wi-Fi mode (which cuts certain Wi-Fi bands when they are not suitable) is activated. You will therefore have to check that this mode is activated by default to see if Free is serious on the subject or if it is a marketing argument. The boss of Free nevertheless emphasized that this is the operator’s first box with an On/Off button to satisfy those who want to turn off their box before going to bed.

Consumption alone doesn’t tell much about the carbon footprint of the box. According to Ademe, an Internet box consumes on average 97 kWh/year, almost as much as a washing machine. Any reduction is welcome, but, as a Senate information report reminds us, “the upstream phase (which includes the manufacturing and transport of terminals) represents 86% of greenhouse gas emissions from terminals”. Use (which includes consumption variables) therefore has a fairly marginal impact on the carbon footprint of a box.

Free also neglects to take into account the rebound effect that the Freebox Ultra can cause. More efficient and faster wifi means more videos, web pages, GIFs and content of all kinds loaded in the same amount of time as with your old box. This means more data consumed by everyone, which increases the carbon footprint attributable to the Freebox Ultra. This rebound effect is difficult to calculate, because it depends on use, but the weight of this variable is important according to Arcep, the telecoms regulatory authority. It can also create a call for air pushing for the renewal of terminals.

Construction: pay attention to marketing

Another argument used by Free is that of sustainability. The operator announces that the Freebox Ultra has “a minimum lifespan of 10 years” and took the opportunity to assert that “at Free, there is no planned obsolescence”. The teams would also have taken care to reduce the quantity of material needed to manufacture the box.

On that point, it’s difficult to nitpick. Since the bulk of the digital carbon footprint is due to the manufacturing of terminals, the longer a device lasts, the more ecological it is. The problem of consumption (and exhaustion) of resources is also important since, as Arcep explained to us in 2022, “the depletion of natural abiotic resources linked to the manufacturing of equipment emerges as an important criterion of the environmental footprint of digital technology”.

On the other hand, to say that planned obsolescence does not exist at Free is perhaps going a little too quickly. In a world where our phones could last 10 years according to Arcep, a box could undoubtedly benefit from an even longer life. We should see the resistance of the materials there; Above all, obsolescence is not just about the wear and tear of components.

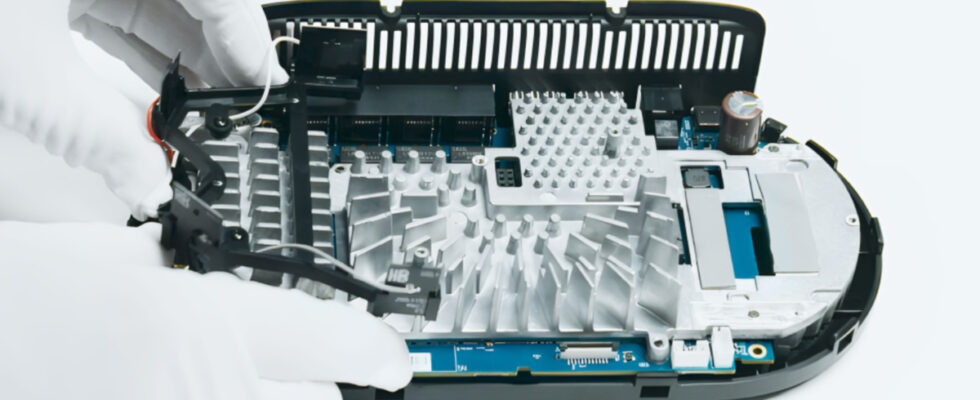

The Freebox Ultra is designed to use fewer resources. © Free

As the Stop Planned Obsolescence association explains, in addition to material obsolescence, there is aesthetic obsolescence, “also called psychological or cultural”. As its name clearly indicates, it involves encouraging, through marketing, the renewal of products even before they break down. Free, like Apple and others, is playing this card to the fullest by promising its customers nothing but wonders with its new Freebox. If a Freebox can last 10 years, but it is renewed every year due to aggressive marketing, this drastically limits the impact of the promises made by the operator.

Repairability, mother of all battles

Finally, the last argument presented by the operator to convince the general public that its Freebox Ultra is the planet’s best friend is that, oh so important, of repairability. In his press kit as during his conference, Free explains that “from the design phase, the Freebox teams also ensured that the repair and refurbishment of the majority of components used were as easy as possible”.

We will have to see to what extent this speech is translated concretely in the manufacturing of the box, but let us already emphasize that such a speech is very rare in the digital industry. As noted by the repairability specialists at iFixit, and incidentally the European Commission, for a product to be truly repairable, it must be thought of as such from the design stage. This is what Free promises by avoiding “gluing the pieces” for example, and it is rare enough to be underlined.

Promises aren’t everything. You will also need to pay attention to the availability and prices of spare parts, as well as the ease of access to different repair methods. The cost of repairs and their complexity are in fact among the reasons most often given to explain the lack of interest of the French public in this industry.

Whether via certified stores, sending spare parts to customers or remote debugging, the repairability ecosystem encompasses many parameters with which you must know how to juggle to offer a truly repairable product. We will have to see what Free has planned from this point of view.

So, eco-responsible or not?

Free has therefore made numerous ecological promises with its Freebox, some of which seem more relevant than others. The use of recycled cardboard and the absence of plastic in the packaging of the Freebox are, for example, arguments very present in the operator’s communication, despite the almost zero impact that this aspect has on the footprint carbon of the box. Others, such as design for repairability, are less emphasized, but much more important.

Releasing a new device of this type in an already saturated market is never carbon neutral, especially when it is accompanied by major advertising campaigns encouraging renewal. But the commitments made by Free are at least in the right direction, even if there are still many unanswered questions.

However, declaring the Freebox Ultra as an “eco-responsible” box is perhaps a bit of an exaggeration. It will only be if it convinces you never to buy another one again. It’s that simple.