Sergei Gerasimov is holding out in Kharkiv. In his war diary, the Ukrainian writer reports on the horrific and absurd everyday life in a city that is still being shelled.

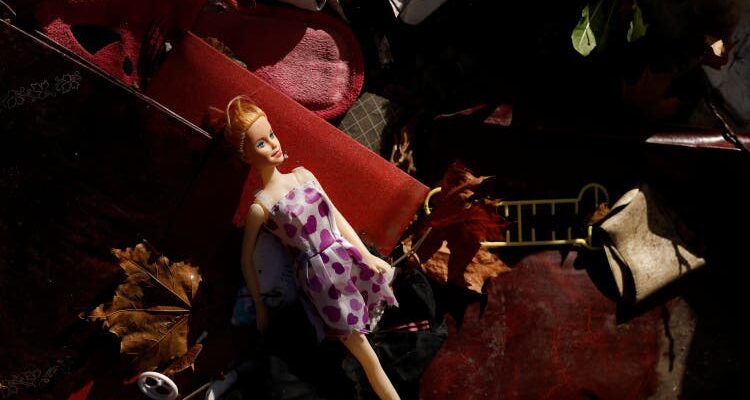

A piece of lived childhood life under the rubble of a block of flats in Kharkiv.

December 2, 2022

Only two of the holes are really big. One of these is on the ground floor and I can walk in as if it were a tunnel going right through the building.

Inside there is nothing but ashes. The fire, which must have been as intense and dense as that in a rocket’s combustion chamber, burned everything that could burn, and the tremendous force of the explosion must have pushed everything else out like steam pushing a piston. What remains is gray, charred concrete.

The corridor seems to be the best preserved. The metal front door bulges slightly and I can see the stairs through the gap between the iron door frame and the wall. The door is locked, from the outside, I hope. When the owners have had time to leave their apartment, they can return, rebuild the destroyed walls, clear away the ashes, then buy new furniture and set up the interior. Sometime in a quiet future.

I climb in through a wall, walk down two rooms, one behind the other, and exit via the low balcony on the other side of the building. I find myself on a pile of rubble again.

The other big hole is somewhere between the sixth and eighth floors. The front door downstairs is open and it looks like I can climb the stairs, so I go inside. The stairwell is littered with small chunks of concrete. The elevator looks intact, and it almost seems as if if I push the button now, its doors will slide apart and it will take me up into the void, into the upside-down abyss.

There are many advertising brochures lying around inside; that was the case before the war. The parcel machine on the second floor stands shattered, as if it had been broken into.

Through the window hole on the third floor I can see the highway, which is only four hundred meters away, and the village of Bobrivka just beyond, from where the Russians fired their artillery and mortars. They shot at close range.

A few floors up, I notice a Christmas wreath hanging on one of the doors. It’s actually only half of a Christmas wreath because the bottom part has broken off. It was still hanging here in February or even early March, more than two months after Christmas, which means that small children lived behind the light blue door at that time. The wreath is made very carefully, there is a lot of love and diligence in it. A small pine branch is glued to the blue ribbon. Walnut shell halves are painted blue and white to look like snowballs. There are colored stars. And tiny Christmas balls, red and blue.

The other half of the wreath lies on the ground among the rubbish. Someone stepped on it and crushed the styrofoam the blue ribbon was wrapped around. I sink into his contemplation, and I feel like I can’t go any higher.

I leave the building and walk along its wall. The force of the explosions threw many small things out of the windows, now covering the asphalt and brown grass. Countless flower pots. Kitchen utensils: forks, spoons, frying pans, all bent. A lot of plush toys have already faded in the sun and rain. Some tattered clothes. Even cardboard egg packs.

I see a white enamel pot that we also have at home. Its lid lies in the grass. A piece of cork is stuck into the handle so that the owner does not burn her fingers. My mother used to put corks on pot lids, as did my grandmother at a time when silicone handles were unimaginable.

There’s only a few small pieces of wooden furniture lying around—I think the rest was hauled away and used for firewood—but what I see is a complete fridge with the door broken off. A couple of small cast-iron pots are still inside, and above them lies a clear packet of pointed Korean carrots that someone bought and put on the shelf but never had time to eat.

But the most amazing thing is the money. The frosty grass is strewn with small coins. No one has picked them up for nine months.

To person

Sergei Gerasimov – What is the war?

Of the war diaries written after the February 24 Russian invasion of Ukraine, those of Sergei Vladimirovich Gerasimov are among the most disturbing and touching. They combine the power of observation and knowledge of human nature, empathy and imagination, a sense of the absurd and inquiring intelligence. Gerasimov was born in Kharkiv in 1964. He studied psychology and later wrote a psychology textbook for schools and scientific articles on cognitive activity. His literary ambitions have so far been science fiction and poetry. Gerasimov and his wife live in the center of Kharkiv in an apartment on the third floor of a high-rise building. The NZZ published 71 “Notes from the War” in the spring and 69 in the summer. The first part is now available as a book on DTV under the title «Feuerpanorama». Of course, the author does not run out of material. – Here is the 75th contribution of the third part.

Translated from the English by Andreas Breitenstein.