There is power in language, and it can be hurtful. I knew that from Albanian when I was not four years old and my parents made the decision to leave home. “Atdhe” was such a word, “homeland”. “Gurbet” was the other, “abroad”.

Our car was heavily loaded when we set off for this foreign country, for this new home. The hope for a better future and the responsibility to enable the family members left behind to have a better life weighed heavily.

One country, two worlds

A new home, security and wishes also filled my backpack when I walked to school for the first time. I had tried to learn German with the television as well as I could.

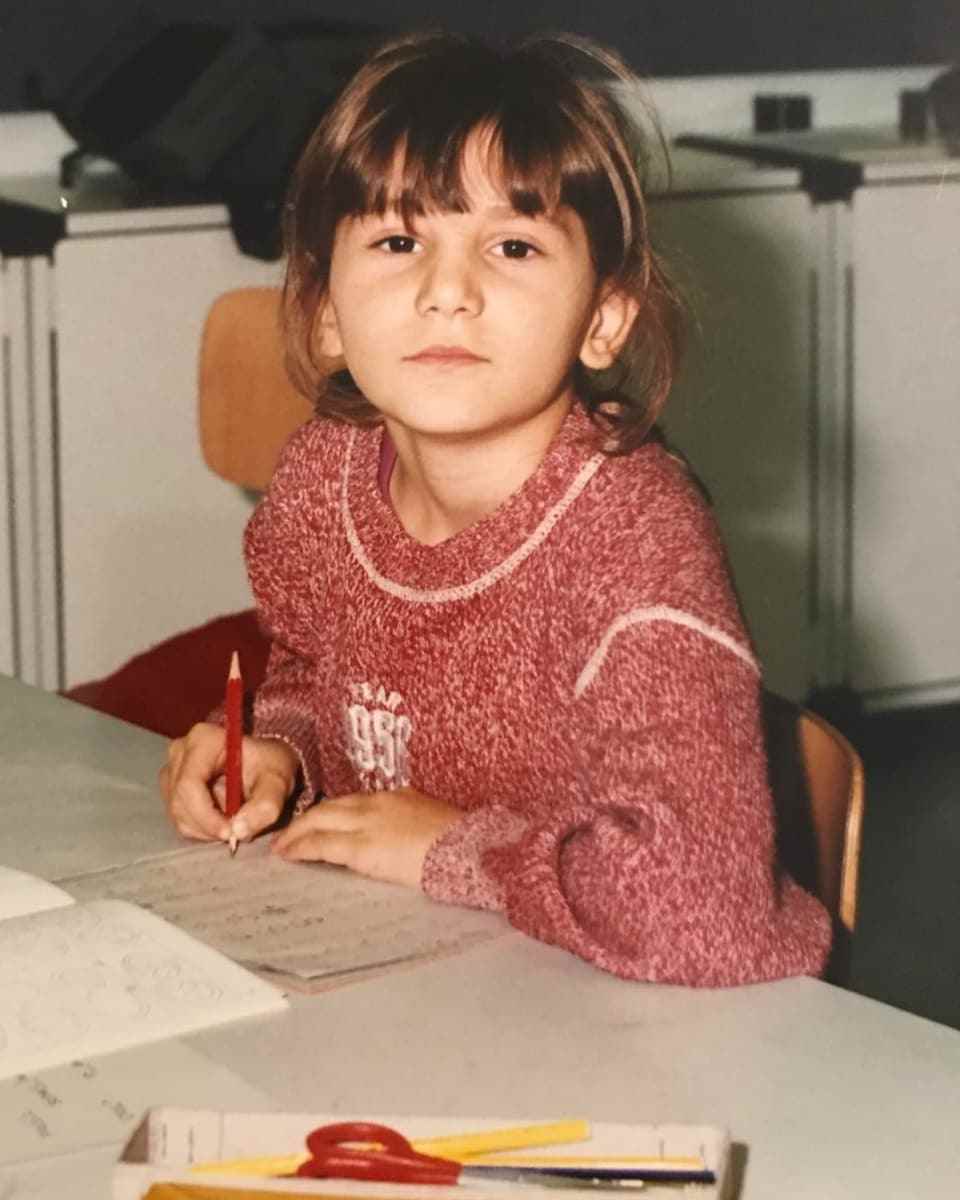

Legend:

Little girl, big question: Why does German sound different on TV than at school? Shqipe Sylejmani – already here in Pratteln.

ZVG

But the language I now heard was more alien to me than that of the cartoon characters. Stranger than those I heard on the news about the wars in the Balkans, which my parents watched anxiously every day.

Between chair and school desk

I was slow to learn this new language. Because it sounded so strange to my child’s ears. So I spoke as I heard them: High German-Albano-Mixisch.

That included my words, my feet, my hands. My rolling eyes and desperation when the teacher tried to explain to me that I couldn’t just sit in on the religion class.

That I don’t have to attend classes at Christmas. That I finally needed different shoes for gymnastics and hiking. That they’re going to inform my parents again and I’ll have to do another detention.

I should simply «integrate» myself. A word that would haunt me for a long time.

Different than the others

I hardly understood the teacher at the time. But I understood that I seemed to be the only one doing something wrong and didn’t learn anything from my mistakes. I understood that I was different from the rest of the kids.

After school, the girls went to “Meitliriegi”, the boys to football. I went home with my brothers, back to our world.

It was a different world, not as ideal as I saw it at Patrizia and Laura’s. Their moms didn’t cry when they watched TV. Most of the time they didn’t have a TV and I watched them learn to read together.

I had been able to do that for a long time – dad had taught me to read and write in kindergarten with the newspaper “Rilindje”. My first written word was “Shqipëria” – Albania. But my teacher didn’t understand that.

King gibberish

And then we moved. The school in our new location was just around the corner and I saw some children playing in the yard on the Sunday before the first day of school. I walked up to them and heard them speak: gibberish. But a whole different gibberish.

What’s my name? they asked. Albanian, they recognized when I said my name. And then other children came along who spoke like me. And others who came from Italy. From North Macedonia, Spain, Croatia and Turkey. Everyone was like me, and I was finally like the others.

forget prejudices

It was the first time that I felt like I had arrived in Switzerland. They were gathered in Pratteln, people from all over the world and found each other here.

They learned together, they grew together. As I got older, people in the city smiled at me when I told them where I lived. “In this ghetto?” they asked.

By now I was familiar with prejudices and was proud that we had a home that “didn’t care”, as it was called. Pratteln did whatever it wanted, prejudice or not.

Just like its citizens: we did not let ourselves be stopped by the borders that were put in front of us. We did our own thing.

“Mrs. Islam”

The new home in Pratteln fit the cliché that many tabloid media portrayed as Kosovar Albanians at the time. As much as one wanted to refrain from a discussion, the society around us expected answers, statements.

Legend:

Exclusion zone Pratteln? The suburb of Basel made headlines in 2016 because of a chemical spill – and before that often because of the multicultural population.

Keystone / GEORGIOS KEFALAS

“Ms. Islam,” a teacher called me during my commercial training and told me about people on disability or social security who, in the anecdotes of his economics lessons, were always Albanians and Turks.

I accepted it so as not to confirm the cliché of the short-tempered Albanian woman. After all, I had found an apprenticeship in this area – you could count the students with my background on one hand in my year’s vocational baccalaureate.

Goodbye Albanian!

The never-ending discussions about our origins led many to become even more deeply embedded in their patriotism.

They didn’t want us here, and the language of the tabloid press had spread among the people around us. Others felt the exclusion and let go of their love for their old homeland.

If one severed the roots of one’s own identity, a void often arose that was very difficult to fill. It took me years to understand that. I began to forget the language – I didn’t need it in Switzerland.

At home we didn’t talk much about life in Switzerland: we all tried to make our contribution to society, applied for the Swiss passport, built a house in Pratteln.

It was the unspoken decision that we put down roots here. Pratteln – Switzerland – was now our home.

Back to the roots

We hardly told the people of Kosovo about the challenges. Poverty, war and a lack of prospects had shaped her life in recent decades. They had had a far greater burden to bear.

For them, Switzerland was the country that offered their families a home and at the same time the place that snatched them away from them every year. Red flags with a white cross still adorn one or the other street where Kosovars can speak a few sentences of German. They learned them every summer when we traveled back.

The Albanian of my ancestors

And one summer it came: the realization of how little I knew my homeland. The mountains and the valleys, the seas and the people, the legends and stories. Also the beautiful language of my ancestors, which had survived conquests and occupations.

I began to read and understand books in Albanian, discovered the country and its people on new journeys. Discovered the part of me that I had lost in the distance, in the «Gurbet».

The stories will soon be immortalized in two novels and are in the Swiss National Library – like every book by a Swiss author. But who would have thought that my name would ever be found under that category in a library?

The Way of Wisdom

Because Albanian literature could not be preserved in the last few centuries, the people of Kosovo passed on their tales orally from generation to generation.

It was my grandfather who inherited the stories full of wisdom from me. When he held my first book in his hands, he could hardly believe that his words could now be read in German.

A few months after the novel was published, I received messages from readers who had traveled to Kosovo and Albania for the first time, with my book in tow.

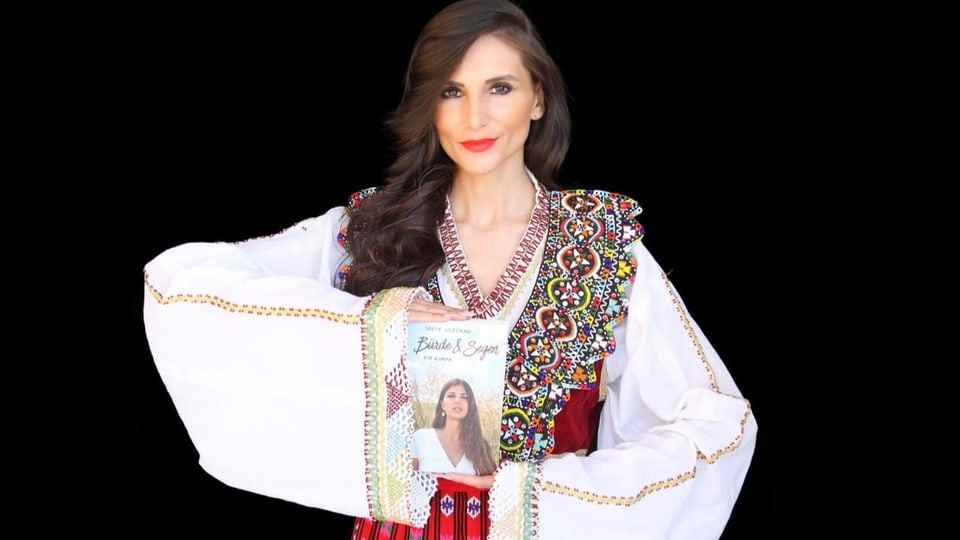

Legend:

Is now in the Swiss National Library – in duplicate: Shqipe Sylejmani’s novel “Burde & Segen”, which was published last year.

ZVG

Why only now, I asked and was often told that the country seemed so far away. Not just for the Swiss – also for the Albanian diaspora itself.

But now there is this work in German, you can read and understand the stories, the culture, the language. In the end it was the German language that opened up this world in the heart of the Balkans to the people.

My grandfather’s stories

A journalist recently asked me why the term «integration» hit me so hard. I tried to explain it to her using an Albanian anecdote.

«People had come together in a village to ask the wisest among them questions about life. In the village, Catholics and Muslims lived together and one of the residents asked the sage what the best religion was. The sage had answered: There are only two religions: the religion of man and the religion of the brute. You can guess which one is the better one.”

This story was one of the last I received from my grandfather. He explained to me at the time that no culture is better than the other. It is important that a culture is kept alive and with it everything that makes it special.

Again and again “integration”

That’s why the word “integration” was accompanied by such a heaviness: it implied to me that I was discarding my culture and the expected “merging” into the new one.

It was not the word that was to blame, but what we humans had created from it. There was probably a wise anecdote for that somewhere too. Maybe someday I would find that lesson. Somewhere between the old home and the new.