Loriot’s 100th birthday

A century of well-mannered timelessness

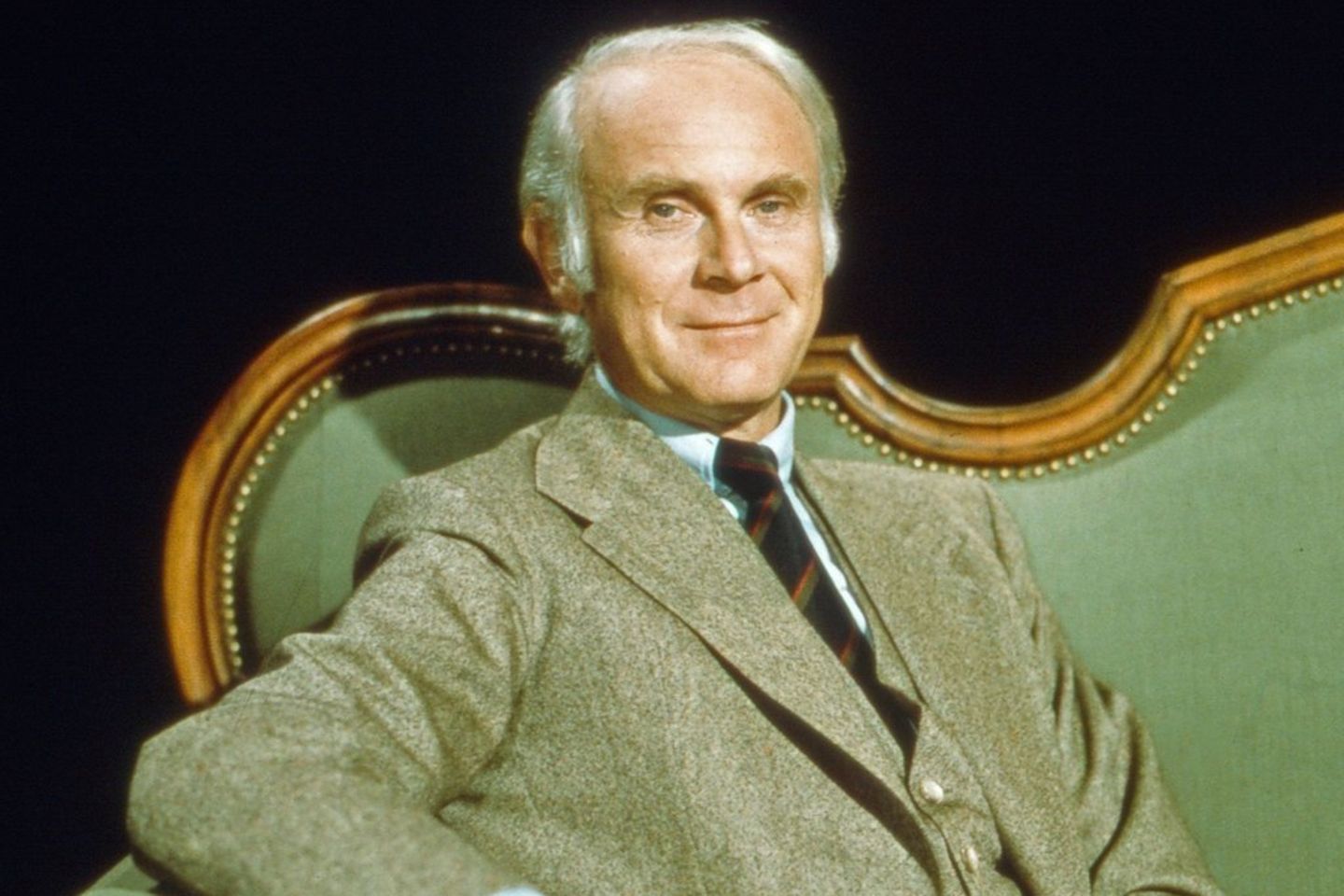

Loriot on his iconic Biedermeier sofa, from which he wrote television history with the finest manners.

© imago images/TBM United Archives

Loriot is considered a timeless classic of German humor. His grandmother played a significant role in his career.

Oh what! Today, November 12th, would be the humorous talent of the century Loriot (1923-2011) turned 100 years old. The fact that he is still very much alive in the collective consciousness of Germans despite his passing in 2011 is demonstrated by the hymns of praise, retrospectives and theme weeks about him that are now springing up everywhere.

The concept of timelessness comes into play with striking frequency: everyone agrees that Loriot’s humor is absolutely timeless, that it still finds an audience across generations and is therefore as relevant as ever. The fact that this is actually the case has primarily to do with the fact that Loriot built a specific type of timelessness into his works from the very beginning.

The timeless fictional character Loriot

An insightful starting point in exploring Loriot’s cross-time effectiveness is the way in which the comic genius, who emerged from an old German aristocratic family in 1923 as Bernhard Victor Christoph Carl von Bülow, presented himself from the start as a personality out of time.

A strangely ageless image of Loriot has been burned into the collective memory of Germans. When one thinks of Loriot, the iconic image of the distinguished older gentleman inevitably comes to mind, smiling obligingly and with a slightly crazy look from a Biedermeier sofa. Even though Loriot has had herself photographed and filmed on the same sofa over the decades, there is no clear aging curve. All the fashions of the time seem to pass the man by without a trace; his suit, like his hairstyle and posture, always have the same classic cut.

This has to do with the fact that a clearly defined fictional character smiles at us from the sofa, but also with the fact that the German audience never got to know Loriot as a really young man. It was only at the ripe old age of 44 that he became a prominent television face after a successful career as a cartoonist.

TV career on the Biedermeier sofa

Already in his first TV show “Cartoon”, in which he presented international animated films and hosted well-known cartoonists for Süddeutscher Rundfunk from Stuttgart between 1967 and 1972, he established his iconic Biedermeier sofa as a trademark and standard background. This was initially red, but it was only when he moved to Radio Bremen, which was extremely innovative and experimental at the time, that he swapped it for the more familiar green seating in 1975, from which he would go on to make television history.

Like the sofa, the way he sat on it and addressed his audience was an unchanging constant throughout his career. From the beginning he consciously aimed to make himself and his characters appear a little old-fashioned and out of time. Above all, thanks to his special, elaborate style of speech, he always managed to make himself seem a little older and more out of date than he actually was.

Like him in one of his last interviews with the Süddeutsche Zeitung revealed, he copied this alienation trick from his father. There he said: “I got that from my father. He loved parodying old men at home. When he himself got old, he was still doing that and at seventy he played a ninety-year-old. I now live with the advantage of not having myself anymore “Having to pretend to move like an old man.”

Childhood in Grandma’s Wilhelminian living room

In the same interview he reported on another biographical factor that had a significant influence on his personal development and that of his Biedermeier fictional character. After his mother’s early death, he grew up in the Wilhelmine household of his widowed grandmother Margarete von Bülow (1875-1945), who gave him “the basics of a useful, old-fashioned general education” and led him “on the piano through the operas from Mozart to Puccini.” .

This old-fashioned and educated middle-class environment in the circle of much older women and gentlemen left clear traces in his work and in his way of self-presentation: “When I drew cars, they were the automobiles from my childhood, doors always had panels, the furniture came from the Wilhelminian era. My characters also never fit into the era in which I drew them. These were the familiar impressions of childhood under the protection of my grandmother. I am very influenced by these remnants of bourgeois romanticism.” As he concludes, this has proven to be an advantage over the years: “Uncontemporary things last longer.”