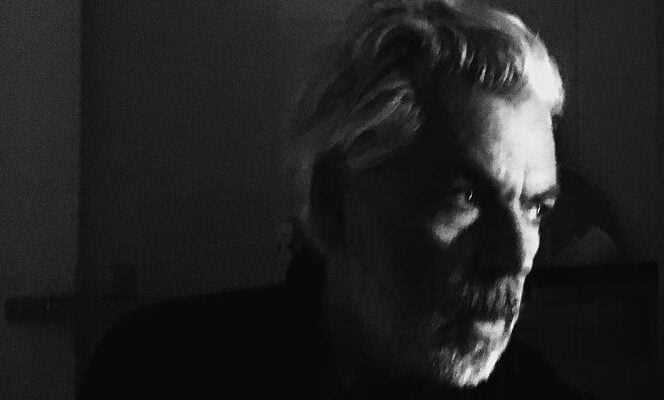

Is he a filmmaker, anthropologist, painter or photographer? The images of Pedro Costa, born in 1959, have this indefinite status which makes each of his films an iconographic treasure, nourished by multiple references – cinema, John Ford, Kenji Mizogushi, Mikio Naruse, but also literature, William Faulkner … The ninth feature film by the Portuguese director, Vitalina Varela, named after its bereaved Cape Verdean heroine, still surprises with the breath of its vibrant plans, echoes of the time and reminiscences of master paintings.

We met the director on November 24, 2020 in Lisbon, when the release of his feature film had been postponed due to the pandemic. The film, Golden Leopard at Locarno in 2019, had to wait two years to find its way to French cinemas.

This chiaroscuro portrait of a barefoot “Madonna” hits theaters on January 12, surrounded by rave reviews. But, for Pedro Costa, nothing beats “Experience” for making this film with Vitalina Varela and the inhabitants of Cova da Moura, an underprivileged district of Amadora, a suburb of Lisbon. Non-professional actress, in her fifties, Vitalina Varela, for her part, received the Leopard for best actress.

In the offices of his producer, Abel Ribeiro Chaves, boss of the company Optec which has produced his films since Do not change anything (2009), Pedro Costa tells the genesis of his film.

It has been more than twenty years since the author of In Vanda’s room (2000), a portrait of a young woman addicted to drugs, cut ties with the film industry. Since then, Pedro Costa has favored the long filming time alongside immigrant workers, filming their vacillating communities over the destruction of habitats and relocations – after Vanda, Forward youth (2006), Cavalo Dinheiro (2014), then Vitalina Varela.

When did you discover the outskirts of Lisbon?

I had the chance to make my second film in Cape Verde, Casa de Lava (1994), produced by Paulo Branco. At the end of the shooting, I returned to Lisbon with bags of gifts, tobacco and letters for the families of Fontainhas.

With my assistant from Cape Verde, we took a car and arrived in the neighborhood, a ghetto, but which for me looked more like a castle, difficult to access. It was a place where one did not enter, with a very important drug market. I said to someone, in Creole: “I am coming to see the son of Madame who lives in Cape Verde, I have something for him.” “I was told,” There it is. We entered and we never left.

You have 67.91% of this article to read. The rest is for subscribers only.