Some works take curious paths to achieve recognition. The name of Mohammad Reza Aslani was thus brought to the attention of film buffs following the rediscovery of a first feature film, The Wind Chessboard (1976), long considered lost. Banned after the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, the film was found forty years later, in a flea market in Tehran.

It was the filmmaker’s son, who came across this dusty stock by chance, who purchased it for the equivalent of a hundred euros. The resurrection, in August 2021, of this poisonous fable rightfully drew attention to Aslani’s second feature film, The Green Flamethirty-two years later, which in turn comes out and shakes up our perception of Iranian cinema.

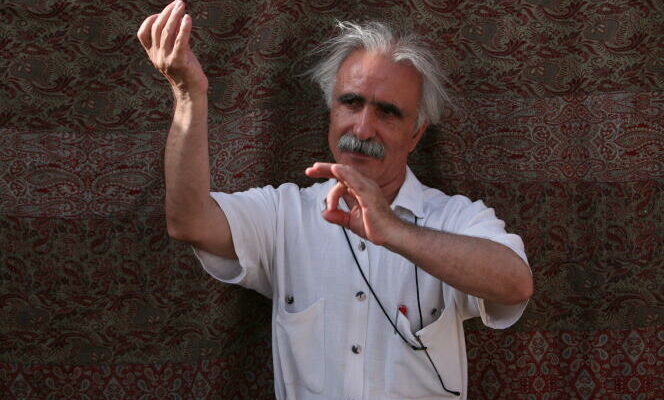

Now in his eighties, living in Tehran, the artist with the appearance of a sage, haughty bearing and bleached fleece, installed in front of an impressive library, lends himself to the exercise of the interview despite a flickering videoconference. The translation is provided, connected from Spain, by his daughter Gita Aslani Shahrestani, who retraces his journey. Born in Rasht in 1943, Mohammad Reza Aslani moved to the capital at the age of 18, with the help of a musician uncle who introduced him to artistic circles.

He studied graphics at the Beaux-Arts, made himself known within a group of young modern poets, claiming through a manifesto a poetry “cubist”said ” From now “. Two years of film school led to his being hired as a production designer by national television, from which he resigned a year later. It was the filmmaker Fereydoun Rahnema, at the head of a research and documentary department, who got him started, commissioning a first short film, The Hassanlou Cupin 1964.

Meditation on Iranian History

The rest seems more painful to hear for Mohammad Reza Aslani, who does not hesitate to talk about ” injury “ concerning the tribulations of his first feature film. Gita Aslani nevertheless insists on one point: the impediments suffered by her father are less the result of political censorship than that of a cinema environment having never accepted him into its ranks. After the setback of The Wind Chessboardcut by its producer, the seraglio would have rather hastened “ to categorize him as an intellectual, overly philosophical filmmaker.” “ You had to belong to the group, otherwise nothing”she specifies, adding: “My father was a free electron. »

You have 42.41% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.