The construction of a new overseas bridge is intended to facilitate traffic in the Indian coastal metropolis. The increasing numbers of huge concrete pillars destroy the fauna on the rocky coastline, and the local fishermen can hardly reach their fishing areas.

Gray concrete pillars grow out of the Arabian Sea. Large parts of Mumbai’s west coast are cordoned off with yellow walls, behind which hundreds of construction workers are working on a major prestige project: a thirty-kilometer-long new coastal road that will give the Indian economic metropolis a modern flair and at the same time reduce chronic traffic jams.

The view no longer reaches far

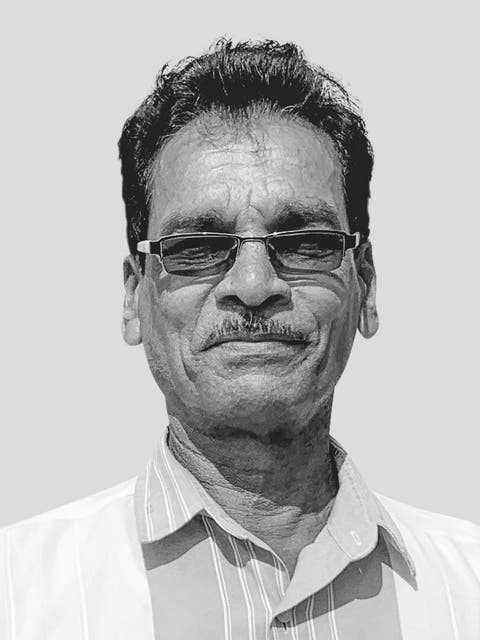

Camillo Quinny, fisherman.

As the pillars of the Überseebrücke rise, the lines on Camillo Quinny’s forehead deepen. The 70-year-old fisherman stands at the Cleveland Bunder in Worli, a landing stage on one of Mumbai’s four peninsulas, and looks out to sea. The view here has not gone far for ten years. Because the new coastal road is just an extension of an already existing giant overseas bridge, the Bandra-Worli Sea Link. This has eight tracks and is 128 meters high, and it runs through the middle of a fishing area.

There are over 40 fishing settlements in Mumbai, home to half a million people. A good 170,000 people are directly dependent on fishing, and urban development is gradually eating away at their living space.

A street for the privileged

The Bandra-Worli Sea Link also stands for the modernization of the city and makes the journey easier, at least for those who can afford the toll of the equivalent of one franc. Mumbai’s biggest problem is traffic, and remedy is to be found in new roads that run over the sea or through an underwater tunnel and no longer lead through the congested city center. The project will at least bring many jobs in the short term, but it will also endanger the sources of income of one of the poorest population groups.

“We fishermen are hindered in our work by the huge pillars,” says Quinny, a man with a mustache and sunglasses. He points to the small boats in the water, which are painted white, yellow and blue, and with his hand he traces the path out to sea, which leads through rocky fairways. “If construction continues without consideration, there will soon be no more passage for us. With the strong surf backcurrent, it is difficult to navigate with our little messengers. We simply cannot drive serpentine lines under these conditions. That’s why we’re protesting, ”he says in a strong voice.

Quinny helped mobilize the Koli, as Mumbai’s fishermen are called. “Mumbai belongs to the fishermen, not just anyone,” it says on their banners. Recently, they were marching through the streets of the city in their traditional clothing – red and blue hats and a loincloth. They had left their boats in the water around the construction sites for a few days in order to force at least a short construction stop.

Pictures for the repo by Natalie Mayroth –

Mumbai’s fishermen are being displaced by a large new coastal road.

Pictures for the repo by Natalie Mayroth –

Mumbai’s fishermen are being displaced by a large new coastal road

Pictures for the repo by Natalie Mayroth –

Mumbai’s fishermen are being displaced by a large new coastal road

The fishermen have come to terms with the modernization of Mumbai, but they don’t want to be forgotten. They fear that they will soon no longer be able to reach the deep waters. Even now it is only possible to drive on the rocky area at high tide. The fishermen are demanding that more space be left between the piers so that they can continue to go out to sea. They hope that at least a compromise can be found in this regard. However, some of them also demand compensation for the loss of income they have already suffered or are expected to have.

In Mumbai there are now hardly any undeveloped shores that are important for fishermen as well as for the marine fauna and flora. The rocky banks are a popular breeding ground for various species. The water sports instructor Pradip Patade has started his citizens’ initiative “Marine Life of Mumbai” to document the biodiversity on the ecologically endangered coast of Mumbai.

Hardly anyone in the city explores the banks and their creatures, says Patade. Stingrays, for example, lived here, and dolphins were sometimes seen in deeper waters.

The coastal strip further north of Worli is also to be built in a second phase, where land is to be piled up on a large scale. Patade, who is already retired, has seen many changes in Mumbai, but the latest construction project worries him more than any previous one.

Grand promises

Since the city is located on an elongated peninsula, there was only one solution for building new residential areas: Mumbai sprawled to the north and east. Important institutions are still located at the tip of the island. So far, the notoriously overcrowded suburban train was the only way to reach the south without long traffic jams. But that should change in the coming years. It is being built on several subway lines.

But that’s not enough, says Niranjan Hiranandani. Old cities like Mumbai in particular have to be completely renewed and the infrastructure adapted to the times, says the billionaire building contractor in an interview. Hiranandani is a man of vision. He is convinced that Mumbai’s transport infrastructure urgently needs relief. “50 percent of the population of Mumbai live in slums or in informal settlements,” says the 71-year-old. “In order to help all of these people, we need a good transport and communication infrastructure.”

Rising land prices

Mumbai was once made up of seven islands that were heaped up. After that, the city grew enormously. “We did something similar to what is happening in Dubai today, a hundred years ago,” says Hiranandani. The current land reclamation is only five percent of what it was at the time of British colonial rule.

“We saw the advantages of the first Überseebrücke,” emphasizes the billionaire, referring to the increased land prices. There is no doubt that the expansion will have a similar effect, all the more since the promenade will also be expanded to accommodate pedestrians.

Pictures for the repo by Natalie Mayroth –

Mumbai’s fishermen are being displaced by a large new coastal road

Pictures for the repo by Natalie Mayroth –

Mumbai’s fishermen are being displaced by a large new coastal road

Pictures for the repo by Natalie Mayroth –

Mumbai’s fishermen are being displaced by a large new coastal road

Rumors of big money are circulating in the fishing villages in Worli. But who knows whether the fishermen can document their land claims. Once one of the seven islands of Bombay, Worli was linked to the other islands by the British in the 19th century. The traditional fishing villages survived these changes in the colonial times. But now they could be suppressed. The area has already become an expensive pavement.

Protests as a last resort

Ritesh Shivadikar, fisherman.

The fishermen had first turned to various authorities, but achieved nothing in this way. When they saw themselves further and further prevented from fishing, they protested. “We are not against the construction work, but we do not accept that the rights of the locals are being trampled on,” says Ritesh Shivadikar, a 35-year-old fisherman.

This is the best time of year to catch fish on India’s west coast. But the Kolis hardly steer their boats out to sea anymore. “The coastal road will one day be finished, but what about the people who live on the coast?” Asks Shivadikar, like the others he is concerned about how he will be able to earn a living in the future.

The major project means an enormous encroachment on nature and has negative ecological effects. Some in the city are convinced that the heavy flooding in Mumbai over the past two years during the rainy season was due to the construction work.

Environmentalists also point out that the city carried out the project with “illegal” building permits. “An attempt was made to circumvent the environmental regulations, which would have required a public hearing,” says Shweta Wagh. The environmental and urban development expert is a lecturer at the Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies in Mumbai and has taken the case to court.

Wagh argues that studies have completely ignored fishing in the shallow waters. The city only discovered in retrospect that people lived from fishing here, she explains. Worli is anything but a small settlement and, with its colorful boats, is easily recognizable from the Bandra-Worli Sea Link. The fisher women who sit in the morning with their straw baskets near the coast and offer fish and prawns are also unmistakable.

Pictures for the repo by Natalie Mayroth –

Mumbai’s fishermen are being displaced by a large new coastal road

In addition to the new connection over the sea, the city government’s plan also provides for new land reclamation. Activists fear that this will have further negative effects on the livelihoods of residents who also fish with small nets or angling in the water. “The Mumbai High Court found that the permits for the project were granted without all the facts having been checked on site beforehand,” says Wagh. She fears that the heaped up areas could be used to build real estate that would not only be unstable but also at risk of flooding.

Still, nobody could stop the project. Wagh also criticizes that the city was much too hesitant to talk to the fishermen. “If they had consulted the fishermen during the planning, this would not have happened,” she says, referring to the protest and the hardened fronts. The fishermen are currently waiting for a promised meeting with the local government. “We want them to at least give us space to continue working,” says Camillo Quinny. If the fishermen got this promise, they would end the blockade of the construction site.