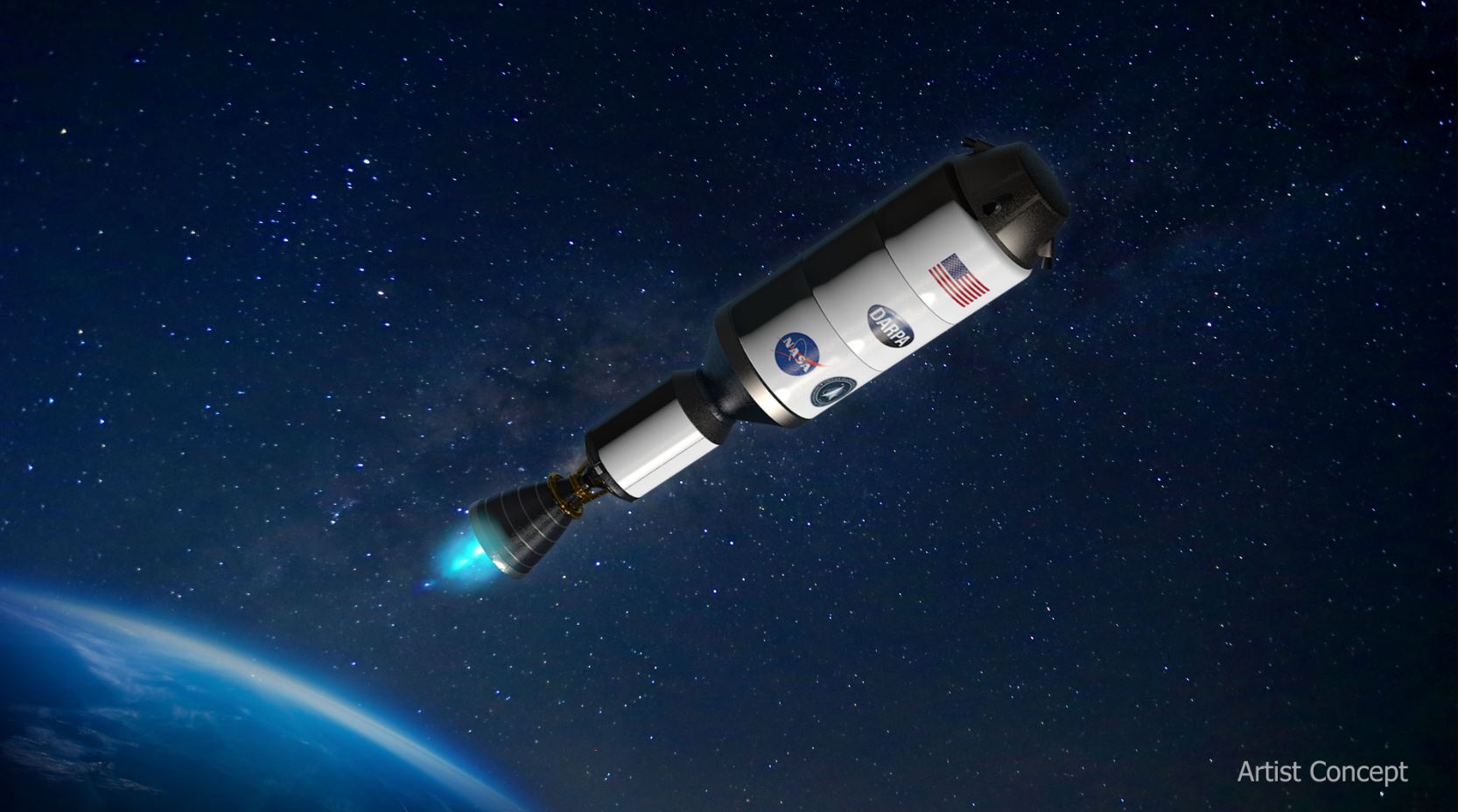

The American agency is progressing on its DRACO project, for a demonstration in orbit of a stage propelled with a small nuclear fission reactor. The flight is planned for 2027, but there are still several technological obstacles to be developed. NASA hopes to use it in the long term for Mars missions.

DARPA, the United States Defense Research Agency, has also gotten its hands dirty.

Towards a very first nuclear rocket stage

All inclusive, the bill currently rises to nearly $500 million. It is certainly a large sum, but up to the stakes which are now partly in the camp of Lockheed Martin. It is the manufacturer who will now act as a reference on this DRACO project (Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations). This one does not specify it in its name, but it aims to develop and demonstrate the performance of a stage powered by a rocket engine equipped with a small nuclear fission reactor.

NASA (300 million) mainly takes care of the research part on the engine and the stage, while DARPA takes care of the authorizations, the mission and the launch contract. BWX Technologies, a company based in Virginia, will deal specifically with the design of the reactor, while Lockheed will be responsible for the floor around it and the integration.

First it heats up, then it grows

The principle is “simple”, at least in theory: a propellant, here hydrogen stored in liquid form, and therefore cooled to a very low temperature (20 K or -253 °C), is injected under pressure and heated thanks to the very high temperature fission reactor (around 2,500°C). Its expansion and its ejection through the nozzle create the thrust, with a theoretical efficiency far superior to that of a rocket engine of conventional architecture. But it has never been tested in this form (this reactor is called an NTP, for Nuclear Thermal Propulsion) in orbit.

With this project, the idea is to produce a demonstration stage that will be sent into space by SpaceX or United Launch Alliance in 2027 (if all goes well). For its launch, it will be inactive and secure. Then, once beyond 700 to 2,000 kilometers altitude, it will be activated and tested for several months.

A lot of work to get to the point

Although the challenge is largely based on the nuclear reactor and the quality of the propulsion (thrust, stability, medium-term performance, etc.), this is not the only technological barrier to overcome. Indeed, having a super-cooled propellant such as liquid hydrogen for periods exceeding a few hours is a veritable showdown against physics. On Earth, this requires large installations, insulators and compressors. For orbit, high-performance materials are needed to keep the propellant passively cold as much as possible, and the lightest possible devices for possible active cooling.

DRACO’s demonstration, if positive, should feed into the projects of the next decade, in particular for Mars, in order to have effective means to reduce the travel time between Earth and the red planet, and therefore to make it more accessible. All of this is still a long way off… Because, like terrestrial nuclear technologies, the idea of sending a small fission reactor into orbit risks, once in its concrete phase, generating an outcry.

Source : Ars Technica

11