Sunday 4th July 2021

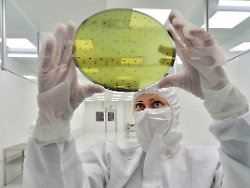

Production on sight

Global chip shortage hits industry in the heart

Microchips are omnipresent in our everyday life – no car, no computer, no machine without electronic components. Since the Corona crisis, however, these parts have also been extremely scarce, the demand is higher than the supply – for a variety of reasons. Is there an industrial crisis looming?

For more than half a year, the chip shortage has been throwing the vulnerable automotive industry out of sync – and contrary to earlier expectations, the supply crisis in other industries is unlikely to subside anytime soon. Chip providers switched to IT or consumer electronics when the carmakers canceled large quantities of semiconductors due to the corona slump. That took revenge. Mainly because the production capacities for the microtechnology installed everywhere became more scarce, also for other reasons.

Why semiconductors are essential

The demand for semiconductors is immense. Almost nothing works in our networked everyday life without these basic electronic components, whose function is based primarily on the properties of the elements silicon and germanium. Unlike strong conductors, these allow the precise control of weak current flows – a basic principle for integrated circuits, the heart of all electronic systems. Even the processing (“doping”) of the semiconductors in clean rooms and the construction of simple modules are complex, not many companies can do that.

And the “demand will continue to rise sharply”, estimates the head of the German electronics industry association ZVEI, Wolfgang Weber. There are shortages everywhere. “The auto industry has also understood that it cannot simply conjure up missing parts.” No modern car without microchips: After the general triumph of computers and smartphones, applications in cars are considered to be the big business of the future for semiconductor manufacturers.

Even before the arrival of e-mobility and networking, engine control units, on-board computers and assistance functions were unthinkable without electronics. The same applies to memories and sensors, which according to the semiconductor expert Ulrich Schäfer “will have significantly above-average growth”. According to Weber, “autonomous driving and infotainment in cars will increase the need for special chips. This also applies to sensors” – for example in traffic infrastructure with signal transmitters on streets or buildings. Semiconductor components such as diodes are increasingly being used in their place in everyday life, for example in the increasingly popular LED lighting.

“Extremely volatile” situation

Almost every vehicle manufacturer has painfully felt the lack of chips: there have been several reports of lost shifts and short-time work since the winter. Recently, the losses on the production lines increased again. The industry association VDA warns: “The supply of semiconductors will remain tense in the second half of the year. We are working intensively around the world to ensure the supply – especially at the chip manufacturer level.” The consulting firm Alix believes that up to 3.9 million fewer vehicles could be built worldwide due to the bottlenecks in 2021.

At the end of June, the VW Group spoke of a continued “extremely volatile” situation. In the course of the first quarter, the Wolfsburg-based company was unable to manufacture 100,000 planned cars. How the second half of the year will turn out cannot be clearly stated. A “task force” looks after the topic of semiconductors around the clock. Further short-time work was introduced in Wolfsburg, Emden and at Skoda. The Audi subsidiary last ramped up production after work stoppages for 10,000 employees in May.

Porsche assumes that the supply itself will remain tense. “But we expect an improvement in the second half of the year.” BMW also had to limit production at the largest European plant in Dingolfing. As early as May, the board saw more fluctuations in the second half of the year – boss Oliver Zipse expects the crisis to drag on for one to two years.

Mercedes-Benz also assesses the situation as volatile: “We will continue to drive on sight.” Here, too, there was already short-time working. At the Opel parent company Stellantis, the chip crisis dropped production of 190,000 vehicles in the first quarter of the year – 11 percent of the planned volume. In the Ford works in Cologne, the production lines had to be completely stopped for weeks due to the lack of semiconductors.

How could the situation improve?

The electronics industry advises customers to reconsider premature cancellations in the future. “A good contribution will probably be to conclude longer-term purchase contracts with suppliers within the framework of what is legally possible,” says Weber, the head of the German electronics industry association ZVEI. Semiconductor expert Schäfer shares this view: “That is how it was in the past, and we have to get there again after the panic reactions of the extreme break-in.”

Other industries also need replenishment: Business is booming at manufacturers of laptops, tablets and TV sets, not least because of the trend towards home offices in the Corona crisis. The same applies to game consoles and hi-fi, high-tech medical devices such as ventilators or magnetic resonance imaging scanners and the core IT segment, as the ZVEI reports.

Where are all the chips supposed to come from if demand should remain so high or even increase – and also force the carmakers back into the market? “The competition between applications has increased massively,” said Schäfer. But semiconductor production cannot be broken over the knee: “You have an average lead time of three months.” At the same time, demand is increasing all over the world: Statistically there are 41 integrated circuits for one person on earth.

Call for a European initiative

There are also buyers for semiconductors elsewhere – in renewable energies, in factory automation, robotics and in all infrastructures that are converted from alternating to direct current and require “power semiconductors”. Politicians like to appeal to German manufacturers such as Infineon, Carl Zeiss SMT or Siltronic / Wacker to invest more.

But it is not uncommon for such factories to cost billions. Bosch has just opened a new plant in Dresden – the largest single investment in the company’s history. The industry believes that funding programs can help decisively. And the raw materials? Many strategically important resources are subject to high delivery risks. This does not actually apply to silicon – it is contained in sand, for example, and is a very common element.

But the refinement to pure silicon, which is an option for chip parts, can vary. According to the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Raw Materials, China was artificially underutilizing its capacities – probably in order to operate “excessive warehousing”. After all: the sand and gravel, which are becoming scarce for construction purposes, do not compete with the chip material.

.