Making a vase or a spare part for a dishwasher is almost child’s play with a 3D printer. But using “living” inks to create an organ and transplant it into a patient is science fiction for now. Researchers are working hard to make it a reality. The first area in which this new regenerative medicine could well change the game, It’s to treat burns.

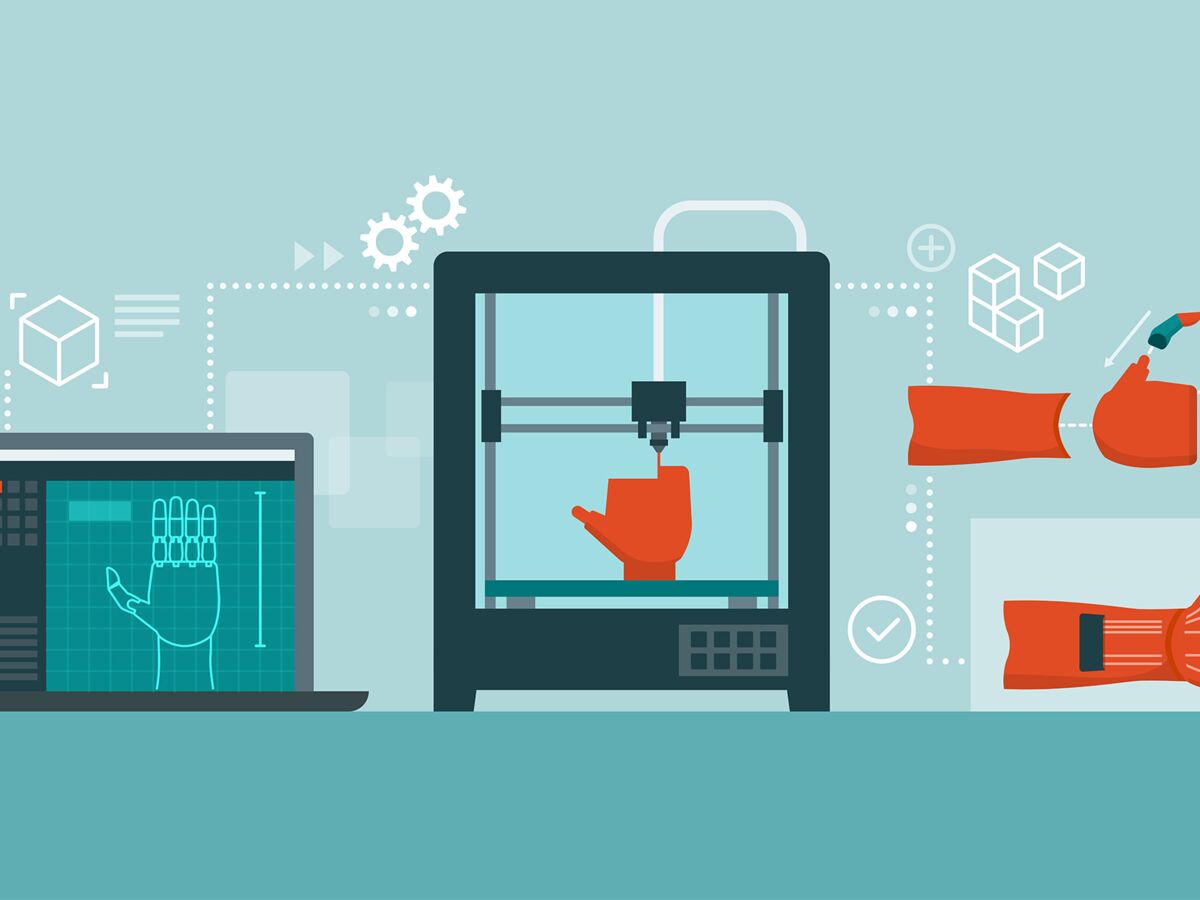

Tailor-made prostheses

Computer-controlled, 3D printing makes it possible to produce custom parts. We print layer after layer until a 3D object is formed, unlike the classic machining technique where we start from a block of material that we cut to obtain the desired shape. 3D printing is thus more precise and wastes less material. In the medical field, the first applications use as “inks” plastics, ceramics or metals to create some prostheses custom made.

Over the past fifteen years, bones of the jaw, skull or even vertebra in titanium or resin have been implanted in dozens of patients. Surgeons also use 3D printing to create cues to practice on before a tricky procedure. In 2021, a team from Winnie Palmer Hospital in Orlando prepared for an in utero operation on a fetus with a spinal malformation. 3D printing also makes it possible to create sorts of resorbable scaffolds on which living cells are then cultured. In practice, we print a custom shape in a biodegradable material, then we grow cells on it to obtain living tissue in 3D. A bit like in topiary art where we use grids of different shapes to grow plants! Clinical trials are underway to create cartilage capable of replacing a nose or a meniscus, for example.

Print with living inks

The real revolution could come from bioprinting : it is a question of printing in 3D with “living” inks, that is to say cartridges filled with cells of skin, liver, cartilage… and collagen, a natural protein which ensures the rigidity of living tissues. The very first clinical trial in this field was launched last year by the American company 3D Biotherapeutics which has created external ear cartilages and has already implanted them in a few patients suffering from microtia, a congenital malformation of an ear external which results in the absence of pavilion. The interest is to use the patient’s own cells, to avoid the risk of transplant rejection, and to print a custom-made ear, symmetrical with respect to the other.

But it’s the most advanced skin impression today. It is already used by the cosmetics industry to test new products, since animal testing has been banned for 10 years. It is also a great tool for researchers who study the functioning of the skin or the toxicity of drugs on it. Printed skin should also soon be tested in humans. As for printing whole organs, liver or kidney type, we are still far from it. This would require being able to use more than ten different bio-inks, in particular to also print the blood vessels and nerves present in each organ. For now, researchers are leaning towards relatively simple organs like the cornea.

Soon 3D printed skin?

“In partnership with the cell culture and therapy laboratory of the AP-HM in Marseille, we are going to launch a clinical trial of bioprinted skin to treat chronic wounds and severe burns. In concrete terms, the first step is to collect a bit of skin in each patient, about 4 cm2, then to cultivate these cells in the laboratory. Then we use them to print a first layer of collagen and fibroblasts, which corresponds to the dermis. After a few days, we print over the epidermis cells. We are thus able to create 40 cm2 of skin that is perfectly compatible with the patient. Then, we let it mature for a few days during which the cells reorganize until they form a thickness of 0.5 cm. All these steps are carried out in 3 weeks, this is also the time it takes for the surgeons to prepare the wound which is going to be grafted. This approach makes it possible to replace the autograft, sometimes impossible when large quantities of skin are needed or when there is no question of creating new wounds that will hardly heal, as in diabetics for example. But before such printers are deployed in hospitals, it will take a little patience! Because printed living tissues are considered drugs, they must therefore pass many phases of clinical trials and then meet regulatory requirements first.”

Thanks to Fabien Guillemot, former Inserm researcher, creator and CEO of Poïtis

Read also :

⋙ Breast cancer: what is 3D mammography, this screening technique now recommended by HAS?

⋙ Cancer: operate better thanks to 3D modeling of the patient

⋙ Serious burns, cosmetic tests… How is human skin reconstructed in the laboratory?