Contents

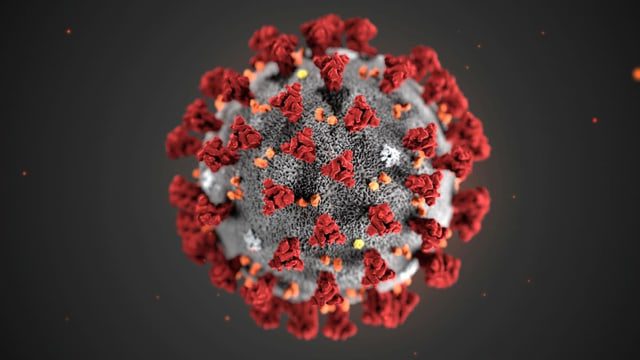

On February 25, 2020, the first infection with the novel corona virus in Switzerland was officially announced. A look back at the beginning of the pandemic. With questions and answers from SRF science editor Katrin Zöfel.

Was the first Corona case communicated by the Federal Office of Public Health actually the first in Switzerland? It was already suspected at the time that it might not really have been the first case – which was confirmed shortly afterwards when the first death occurred. It was known that a deceased person inevitably meant many other cases that were possibly only slightly ill and that were only partially noticed.

What do you know about the routes of infection? It was initially not clear whether the virus is transmitted via objects and surfaces, whether long-range aerosols play the main role or whether it is mainly droplets that only allow transmission over short distances. It was also unclear how contagious it would be. But still: At the time when the first case became known in Switzerland, the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV2 was already known and there was already a specific test for the virus – and that was only eight weeks after the first reports.

On March 15, the Federal Council ordered the shutdown – on what scientific basis? A lot was still unclear, but it had become clear that the virus, once it was there, could quickly trigger strong waves. That was the experience in Wuhan, and it was evident these days in northern Italy, where the number of cases and deaths has skyrocketed. The time factor was therefore decisive, it had to be done quickly. At that time, many experts compared the situation to that of an emergency doctor who had to make quick decisions with less than optimal knowledge.

How good was the information from China? On the one hand chaotic. The official number of cases had just been corrected from 4,000 to 20,000. Practically at the same time was also the first major study with a good 70,000 patients from China before. At that time, the doctors calculated a case mortality rate of a good two percent – with a significantly higher mortality rate for those over 80 years of age. From here it was very difficult to assess the number of unreported cases: If many cases had been overlooked or omitted, the mortality rate would be much lower – if many deaths had not been counted in the whole mess, it might have been higher. That was completely open at that point.

When did the vaccines come? Ten months later, the first vaccine, the Pfizer/Biontech vaccine, was approved, followed shortly thereafter by Moderna. In February 2020, nobody dared to predict that it would happen so quickly. It was assumed to be at least a whole year, also because there had never been any successful vaccines against corona viruses before. Without the new mRNA technology, effective vaccines would probably not have been available so quickly. Shortly thereafter, vaccines produced using fundamentally different techniques also provided efficacy data – albeit not nearly as good as the first two.

A lot was not known at the beginning – are there also things that you actually knew and could have done better? Maybe some general points in dealing with information and uncertainty. It’s not easy to say loud and clear in a crisis situation that there’s a lot you don’t know yet. But that’s the way it was. Initially, little was known about the virus itself, about the disease, but also about the possible benefits of masks or how strongly children acted as drivers of the pandemic. Later that applied to the vaccines. Knowledge only developed over time. It could have been communicated better, perhaps it should have been.