We must never miss an opportunity to immerse ourselves in the masterful work of Indian Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray (1921-1992), and even more so in his inaugural “Apu Trilogy”, which comes out in the new clothes of a restoration digital. Because there is undoubtedly what is best about cinema at play: a sensitive form crossed by profound currents of life.

In fact, this polyptych brings together an entire educational novel: three parts which focus on childhood, adolescence, then on the entry into the life of a boy born poor in a village in Bengal. . The whole has lost nothing of the aesthetic shock that the first part produced in its time, The Path’s Lament (1955). At home, this masterstroke opened the way for a realistic school facing the hegemony of Hindi entertainment and its sung fantasies; abroad, a window on a world, Bengali rurality, which had never hit the screens.

However, it is indeed fiction that “The Apu Trilogy” comes from, and even doubly so: Satyajit Ray, from a high Bengali lineage, evokes a childhood at odds with his own, by adapting the autobiographical novel of his compatriot Bibhouti Bhushan Banerji (1894-1950), period story dating back to the 1920s. However, the young filmmaker, who had attended the filming of River (1951), by Jean Renoir, in Calcutta, has not forgotten the example of the master, nor the conquests of Italian neorealism. He combines these influences and pushes them even further, merging the drama into the luxuriant forms of nature, daily rituals of Bengali sociability (eating with the hands, greeting elders by touching their feet, adjusting a sari), of the languid course of time and climatic variations.

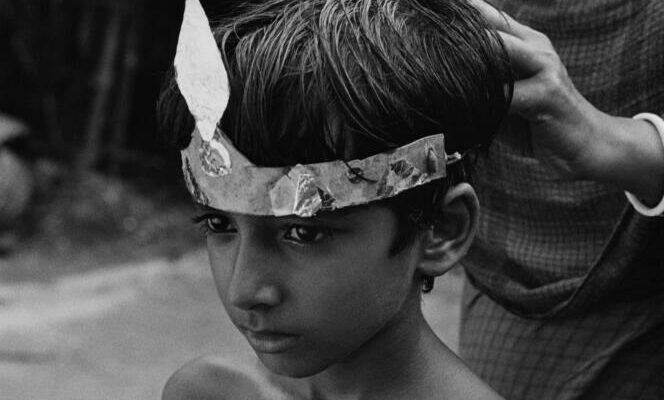

The Path’s Lament tells the birth of Apu, son of a Brahmin, and his first years, but even more the birth of the world which happens every time a child’s gaze is placed on it – and we no longer count the close-ups on his face with large, wide-eyed black eyes, eager to swallow up the expanse. While the toddler frolics with his elder sister, Durga, his father, dreaming of literary glory, carries like a burden the ancestral home where he has returned to settle, with the sole income of reciting funeral rites. The mother (a magnificent character, lovingly tough) is responsible for the household economy, an impossible equation with so many mouths to feed (including a toothless old bitch of a grandmother), and without the resource of the orchard ceded to the neighbors for debt. , subject of incessant litigation.

You have 50% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.