A hundred years ago, the Czech writer and inventor of the soldier Švejk died.

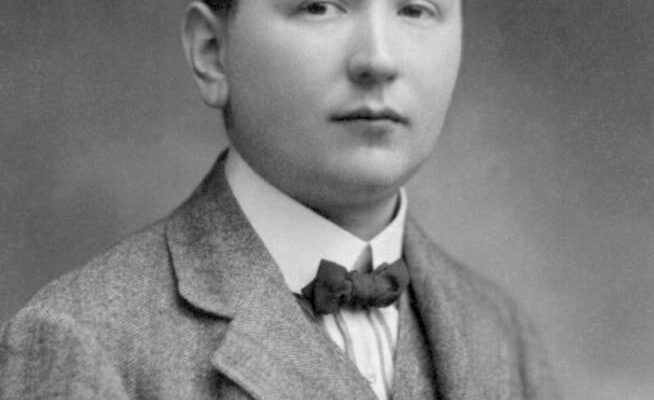

Jaroslav Hašek got to know the misery already in his youth: his father was a heavy alcoholic, he should follow him in it. (recording from 1897)

The astonishing drama of Jaroslav Hašek: Perhaps his famous novel «The Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk in the World War» could have been invented a little better, but not the writer’s life. Hašek discovered lies about Catholicism early on. However, the altar boy, who was inclined towards gambling, quickly catapulted himself out of the lap of the church. Later, Hašek was a druggist’s assistant until he hoisted a maid’s petticoat over the rooftops of Prague as a red flag.

For a time the writer was also an animal dealer. The fact that he changed the color of stray dogs into pedigree dogs fits in with other decisive interventions in biology. As the editor-in-chief of the formerly respected newspaper “The World of Animals”, Hašek invented a whole menagerie of new species. Primeval fleas, giant angora rabbits, sulfur belly whales and leather-scaled unicorn calves. “I have changed politically. I’m with the animals now,” writes the author with undeniable ambiguity.

An animal world, for Jaroslav Hašek that was the human world. raw and dumb. The Prague author contrasted stupidity with a literary equivalent that exaggerates it and thus overcomes it at the same time: the rheumatic World War II participant Josef Švejk, who, however, was not to make it to the front. Jaroslav Hašek dies before he can finish dictating his novel. He is 39 years old.

Jaroslav Hašek, born April 30, 1883 and died January 3, 1923, was a living example of the fragmentation of an epoch. While he himself went through times of wars and revolutions, these times also went through him. They wreaked havoc. Mentally and physically. According to his doctor’s report, Hašek had a regular intake of thirty-five beers a day.

He was a delirious permanent guest in the taverns of Prague, where he made his own texts from the stories of the other guests. He listened, compiled and read what he had written straight away. Reality was the engine of a work that was less about literary alienation than about the alienation of people in their own lives. Jaroslav Hašek was an example there too. He had to write a lot to pay for the many beers without which he could not have written.

He is evil par excellence

Everything that the Czech writer invented is true. Many of his prose pieces describe how children who have to submit to fate later become adult subjects. The misery of Prague is above all the misery of the children, as Hašek knew it. His father was a depressed alcoholic who drank quietly in his room.

In the epic self-incriminating text “My Confession”, the son Jaroslav takes all the blame on himself and presents himself as the ultimate evil. At the age of three months he had bitten his wet nurse to death and a short time later ate his brother. “My father hanged himself out of grief at my depravity. My mother jumped off the Charles Bridge and when they tried to save her, the boat with the rescuers overturned and they drowned too.”

The catastrophe is total, and even if all of this is just a lie, Hašek was already well acquainted with the degenerate areas of Prague when he was a child. A certain Mr. Němeček, formerly a sailor, later a thief and a pimp, wandered around the brothels with the then eleven-year-old. There is said to have been massive sexual abuse. There is a booming comedy in Jaroslav Hašek’s rascal stories that makes it easier to remain silent about what is serious.

One of the locational disadvantages of humorists is that they often have to spend a lifetime and even longer in the dingy corners of the literary canon. In a “Švejk” review, Max Brod called Hašek a “humorist of the greatest stature”. Later one would compare him with Cervantes and Rabelais. Hardly anyone compared Jaroslav Hašek with his contemporary Franz Kafka. However, the two formed a rival duo in Prague that could hardly have been more prototypical. They worked in two different languages and in different cultural spaces.

anarchist and revolutionary

The homeless, vagabond Hašek was a victim of those conditions that Kafka, the artist of retreat, turned into parabolic stories at his desk. Kafka reinvented what Hašek had experienced first-hand in the bureaucracy, in the war and in the Russian camps. He described it in German with that drasticness that the Czech author wanted to drive out of his own texts beyond recognition.

It is unclear whether Kafka and Hašek ever met. There could have been an opportunity for this in Prague’s «Klub mladých», where anarchists met. The author of «The Trial» will have quickly knocked the little gunpowder of anarchy out of his suit, while Jaroslav Hašek was a revolutionary through and through.

As a Czech, the writer opposed the Viennese Emperor, the Crown and all the authorities in the system. He agitated among the Bohemian miners and demanded freedom anarchist fashion. In his fight for freedom, Hašek was a man of conviction. He didn’t fit into the bourgeois world, as the reactions of rejection on both sides show.

The way of life of the original genius followed the zigzag of his alcoholism and economic necessities, which could only be halfway brought under control through feuilletonistic mass production. With his wife Jarmila, Jaroslav Hašek fathered a son named Richard, who he only saw twice, because the key witness to this misery, the father-in-law, ordered Jarmila’s husband finally thrown out.

When the great war came, there was euphoria and disillusionment at the same time. Like his hero Švejk, the rheumatic Hašek also moved to the garrison in České Budějovice in January 1915 while singing old military songs. In the coming years he will not only temporarily renounce alcohol, but also his dual monarchist Austrian homeland.

“Four times dead and yet alive”

As early as autumn 1915, the quite useful soldier was voluntarily taken prisoner by the Russians. The hope that the defected Czech would be met with pan-Slavic friendliness is disappointed. Cruel conditions prevail in the prisoner of war camps. Later, Hašek was able to join the so-called Czechoslovak legions within the Russian army and agitated publicly against Austria.

When the Bolsheviks came to power in Russia in 1917 and signed a separate peace with Germany and Austria, the Czechs came under pressure. Jaroslav Hašek has gotten caught between the fronts and is threatened with summary death. In 1918 he joined the Communist Party in Moscow and became political commissar of the Red Army.

In 1920 he was to become politically active in Prague. They send him back, but Hašek wouldn’t be himself if he didn’t immediately join his old troops: the bohemian people of Prague’s Žižkov district. The return of the strange hero has not escaped notice of the newspaper «České slovo» («The Czech Word»). It is titled: “Four times dead and yet alive”.

Back home, Jaroslav Hašek begins to write down his «Švejk», of which there have already been earlier versions. He will continue to work on the work in the small town of Lipnice nad Sázavou, south-east of Prague, until his sudden cardiac death on January 3, 1923, heavily advertising it on yellow posters. Hašek can at least guess at the success of his «Švejk». The novel propelled Czech literature into a humorous modernity from which it will not escape. The absurdity of the world is reflected in the book of an author who was an anarchist at heart: a ringleader out of helplessness.