Since 1972, 27 seconds have been added to Universal Time to keep it in sync with astronomical time. Right now this will finally end up here. In the future, the world time should flow continuously.

The Greenwich Observatory in London has long been the hoard of time.

The leap second will soon be a thing of the past. On Friday last week the General Conference on Weights and Measures took place in Paris decided, that from 2035 no more extra seconds will be added to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). You will notice little of it. And yet the decision is historic.

Abandoning the leap second will lead to universal time and astronomical time drifting apart more and more. At its next meeting in 2026, the General Conference on Measure and Weight wants to decide how big the difference can be.

Technology needs a reliable time scale

The internationally coordinated world time is the cement that holds our technical world together. A digital clock is ticking in every computer, coordinating the work processes. If these clocks get out of step, there are drastic consequences. In the worst case, computer, power or mobile phone networks can no longer be synchronized, high-frequency trading on the stock exchange collapses, or navigation satellites provide incorrect location information.

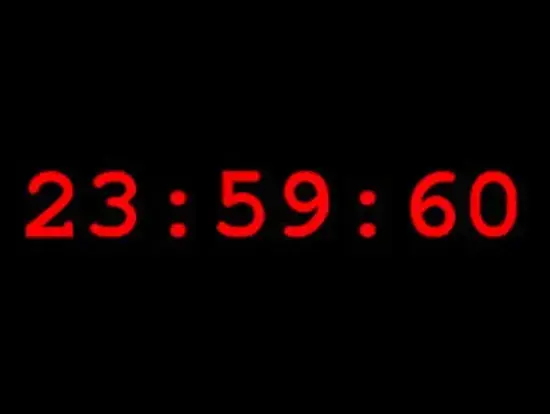

Adding leap seconds to Universal Time is technically challenging. Digital clocks are not designed to take an artificial break between 23:59:59 and 00:00:00. And there are no universal recipes for this. Tech companies such as Google, Facebook, Alibaba and Microsoft have each developed their own methods of inserting leap seconds in their computer networks. So far it’s been good. But nobody wants to put their hand in the fire that it stays that way. For this reason there have been efforts for many years to abolish the leap second and to make universal time a continuous time scale.

Such a time indication is not provided on digital clocks.

A new era of time measurement begins with the atomic clock

Coordinated Universal Time is not that old. Until the middle of the 20th century, time was determined astronomically. People used the position of the sun or fixed stars in the sky for orientation. The length of a day, an hour or a second was linked to the rotation of the earth.

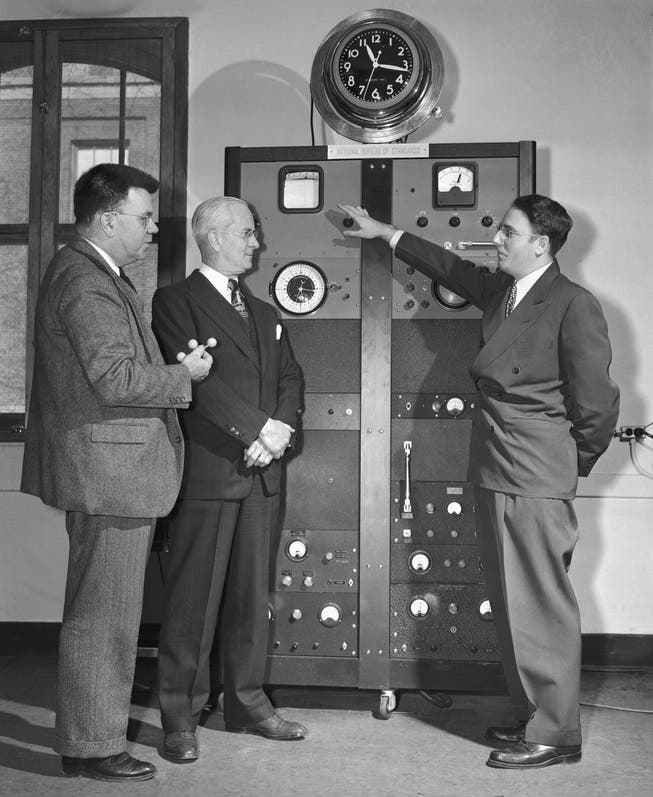

This began to change with the invention of the cesium atomic clock in the 1950s. In these clocks, the clock is given by the oscillation of cesium atoms. Such atomic clocks spread rapidly. And so, in the 1960s, an international atomic time was established parallel to astronomical time. This was determined by averaging over several atomic clocks in a complex process.

It quickly turned out that astronomical time and atomic time are not synchronous. This is because the Earth’s rotation slows down over time. Year after year, astronomical time lags a little further behind atomic time. A compromise was therefore agreed. The world time was synchronized with the international atomic time, but adjusted again and again to the astronomical time. This made it possible to use the stars to determine your position, which is widespread in seafaring. (There were no navigation satellites back then.)

The adjustment initially took place several times a year in small steps. In 1972 it was decided to insert a leap second in the coordinated universal time whenever the difference between astronomical time and atomic time is greater than 0.9 seconds.

Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology) physicist Harold Lyons (right) explains how an atomic clock works.

27 leap seconds in 50 years

In the last 50 years there have been 27 leap seconds; the last one was added at the turn of the year 2016/17. It is not possible to predict when the next leap second will be due. Because the earth’s rotation changes in erratic ways. While it has slowed down in recent decades, it now appears to be accelerating again. It is therefore not impossible that in seven to eight years there will even be a negative leap second. So the digital clocks would have to skip a second. Technically, this has never been tested. That was an additional reason to abolish the leap second.

Nevertheless, there had been resistance to the reform of the world time until the very end. They came mainly from Russia. The reason for this is that the Russian satellite navigation system Glonass follows the jumps of the world time. The omission of leap seconds requires technical adjustments, for which Russia would have liked to have had more time.

Other countries, on the other hand, had pushed for a faster abolition of the leap second, says the director of the Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology Metas, Philippe Richard, who took part in the vote as a Swiss delegate. The year 2035 was agreed as a compromise. However, an earlier implementation cannot be ruled out.

Unlike Glonass, the American GPS, the European Galileo system and the Chinese Beidou system do not use leap seconds. So their internal time scales have what universal time lacks: they are continuous. This also makes them attractive to other users. For example, the International Telecommunication Union recently recommended making GPS continuous time the reference time for telecommunications networks.

Engineers prepare a Glonass satellite for launch.

The star clock from the 16th century made it possible to determine the hours of the night based on the position of the stars.

The Antikythera Mechanism dates from 70 to 60 BC. The device can be compared to an astronomical clock.

Astronomical methods of measuring time go back to ancient times.

The world time belongs under international control

The danger that world time would be superseded by another time system made alarm bells ring among the guardians of world time. Just recently, two senior members of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures warned against it should not be left to the American military to define time. The world time belongs under international control. That argument favored the General Conference’s decision on Weights and Measures, Richard said.

The next general conference will be held in 2026. By then, the International Committee for Weights and Measures is to work out a proposal for the maximum difference between universal time and astronomical time. If you agreed on one minute, you would probably have peace for the next hundred years. If one even allowed a deviation of one hour, one would have several thousand years to consider how to bring universal time back into line with astronomical time.

An hour sounds like a lot. However, the effect on the position of the sun would be the same as when switching from winter to summer time. Richard sees no major problem for astronomers either. Even today, the differences between universal time and astronomical time are measured and documented very precisely. Those who depend on it can continue to use astronomical time.

Follow the science editors of the NZZ Twitter.