For a long time it was considered the nation’s bestseller. But the telephone book was always more than just a directory: an obituary for a Swiss cultural asset, a place of remembrance and “Google avant la lettre”.

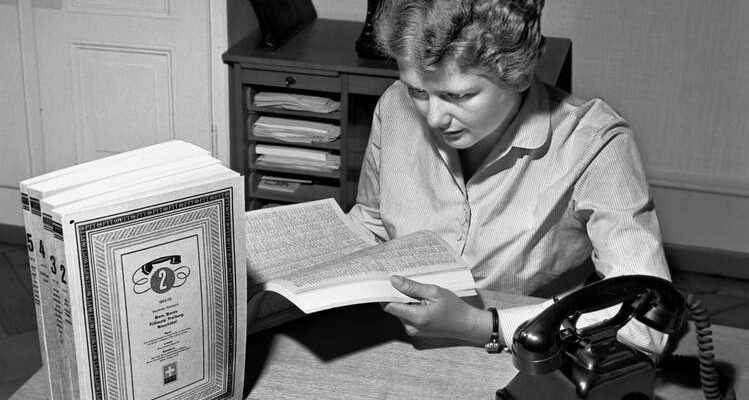

Belonged in every household for decades: the Swiss telephone book. In 1954 a new edition was introduced in a larger format. The PTT archive in Bern has a collection of all telephone directories in Switzerland.

For decades, the telephone book was part of the inventory of every Swiss household. Anyone looking for a hairdresser nearby or a distantly known great aunt will find what they are looking for in the no-frills book. Until 1992, an entry was mandatory for everyone with a landline. “Everyone could look up where they lived and how to contact celebrities and politicians,” says Juri Jaquemet, the collection curator at the Museum for Communication in Bern. “Maybe not exactly the Federal Council, but most of Switzerland was to be found in it.”

That would be unthinkable today. Fewer and fewer people publish their private number. Only those who have a landline are in the phone book. Anyone with a mobile phone number must actively register for this. “But almost nobody does that,” says Stefano Santinelli, CEO of the telephone directory manufacturer Localsearch.

After 142 years it’s over

What’s more: with the smartphone, everyone carries their own phone book in their pocket. Who is still looking it up in a book?

In 2016, three out of five Swiss people said they picked up the book at least once a month. But digitization, which heralds the end of many an institution, not only pushed the landline and the telephone booth in the village to the brink of insignificance, but also the nation’s bestseller. The current circulation is 1.9 million copies. In recent years, more than 150,000 recipients have reported and proactively unsubscribed from the phone book, says Localsearch boss Santinelli.

Now, after 142 years, the printing of the “White Pages” is being discontinued. The Swiss business directory “The Yellow Pages” continues to exist.

When the “Miss from the Office” mediated

The private Zurich Telephone Company published the first directory in 1880. It included 99 entries in the city of Zurich – including the NZZ – and was called “List of speaking stations”. Because back then you didn’t dial a number on the display or the dial. “You called the ‘Miss von Amt’, who then put you through to the person you were talking to,” says historian Juri Jaquemet from the Museum of Communication. Over the decades, the number of entries grew rapidly, culminating in the 1990s when the thin sheets covered over 4.2 million numbers.

The phone book always told more stories than the boring lines suggested. «When did psychiatrists appear, when did gyms? In which neighborhoods in German-speaking Switzerland did many Italian names suddenly appear? Where did your ancestors live? The telephone book is just as valuable a source for economic and migration history as it is for family research,” says Juri Jaquemet.

As interesting as it may be as a research object, the relevance for the individual is rooted in everyday life. “For the generation up to and including those born in 1980, the telephone book is a place of remembrance,” says Jaquemet. “Everyone associates an experience with it.”

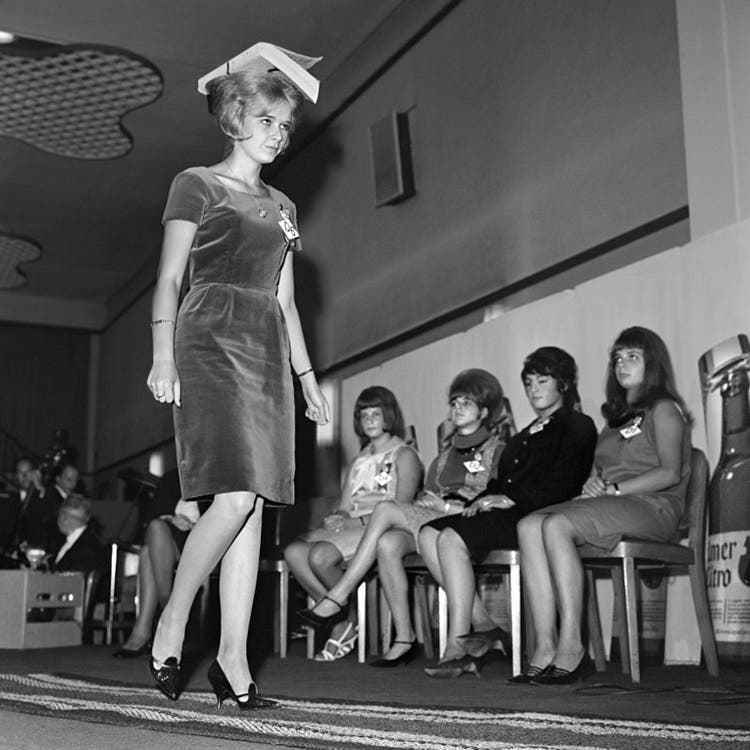

One of the 54 candidates for the Elmer Girl election covered a short distance with a telephone book on her head during the preliminary round in 1964 in the Kongresshaus in Zurich without it falling off. This was one of the tasks on which the women were judged by a jury.

The cultural asset also had a very practical function: the front or back of each issue contained a page with the siren signals and instructions on what to do in the event of a nuclear war, for example. Then you read: “Close the doors and windows, immediately go to the nearest shelter or basement, take the transistor radio with you and follow further instructions.”

That was particularly important during the Cold War, says Jaquemet: “To put it bluntly: Thanks to the telephone book, everyone knew what to do when the Russians came. So the phone book also documents a history of fear.”

The Lucerne Carnival will miss the phone book

In addition, the phone book contained a colorful hodgepodge of information. Jaquemet describes it as “Google avant la lettre”. Instead of an algorithm spitting out what you were looking for, you had to look it up manually in the printed data store. The telephone book was therefore also a cultural technique, says Jaquemet. You had to learn to find your way through the thicket of names and towns just as much as you had to learn to read the timetable for the federal railways.

When the SBB discontinued this tome, private initiators were found who published a slimmed-down version of the timetable. Is such a revival in the telephone book also conceivable? Localsearch boss Stefano Santinelli says that from 2023 you will be able to obtain the telephone directory for your respective municipality free of charge as a PDF. “If someone were actually interested in continuing to print a telephone book with private numbers, it would be possible.”

The last number not only saddens nostalgics, but probably also the people of Lucerne. When the Fötzeliräge falls over the old town on Dirty Thursday after the Big Bang, kilos of cut up telephone books fall to the ground. The carnival crowd, however, have taken precautions. «We have stored a few tons of telephone books. The Fötzeliräge is still guaranteed for the foreseeable future, »says Alexander Stadelmann from the responsible guild for saffron. By the time the last phone book is gone, he is confident that the guild will have found an alternative.