A special ship is on its way to Tonga, but won’t get there for a week. Only then can the repair of the submarine cable begin. Who is laying important telecom infrastructure and where in the South Pacific is also a geopolitical question.

The special ship “Reliance” is on its way to Tonga to repair the undersea cable.

A small, very slowly moving dot on websites that record ship movements, symbolizing hope for Tonga. The Reliance left Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea, on Friday evening local time. The special ship is to repair the undersea cable that connects Tonga to the global Internet.

Since the eruption of the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano on January 15, the connection has been interrupted. Tonga was completely cut off from the outside world for several days, but telephone calls via satellite are now possible again. However, what the satellite makes available in terms of bandwidth is only a fraction of the performance of the undersea cable. Tonga won’t have fast internet again until the cable is repaired.

Fiji is the internet hub of the South Pacific

Until then, the residents of Tonga will have to be patient. Port Moresby is more than 4,000 kilometers from Tonga’s capital Nuku’alofa – it takes more than a week for the “Reliance” to get there. And then the repair work will only begin. It will probably take another month before the line is repaired.

The problem for Tonga and its approximately 100,000 inhabitants is that their country is hanging on a single cable. Laid in 2013, it runs 827 kilometers on the seabed to Fiji, where it is connected to intercontinental cables. Fiji is a hub for internet connections in the South Pacific. Cables run from here to Sydney in Australia and via Hawaii to the USA.

Tonga is far from the only South Pacific country hanging on a single internet line. The same applies, for example, to Vanuatu, Kiribati or the Marshall Islands. All of these islands face the same problem as Tonga: their populations are in the tens of thousands each. And they are hundreds of kilometers from the nearest islands. The costs per connected person are enormously high. The fact that there is no backup for the communication line that is so important is problematic: natural disasters are very common in the region.

However, natural disasters are not the greatest threat to submarine cables – statistically speaking, they are only responsible for about 6 percent of the interruptions. The cables are much more frequently damaged by fishing or the anchors of large ships. To prevent this as much as possible, submarine cables are marked on nautical charts, and anchoring is usually prohibited where they come ashore in shallow water. Nevertheless, ship anchors are responsible for around a quarter of cable breaks, as the specialized site Telegeography.com writes.

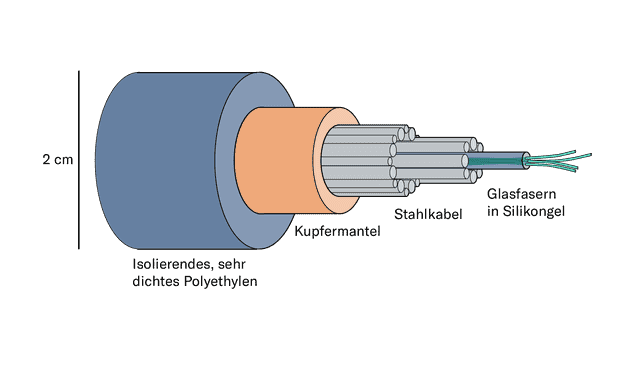

In January 2019, the cable to Tonga was interrupted for two weeks. The damage was probably caused by an anchor at the time. Although submarine cables can transmit enormous amounts of data, they are only about two centimeters in diameter. The hair-thin optical fibers through which the data is sent are protected with steel cables and an insulating jacket. Nevertheless, according to Telegeography.com, damage occurs somewhere in the world about a hundred times a year, leading to a disruption. Then a ship like the “Reliance” has to move out – but there are only a few of these special ships.

Cable laying race

The cable that leads to Tonga previously belonged in part to the Jamaican company Digicel. In October Digicel announced that it would sell its Pacific operations to Australia’s Telstra. Although Telstra is privatized, it is known that Australia has an interest in the telecom infrastructure in the South Pacific.

In the recent past, undersea cables have become part of the geopolitical struggle taking place in the South Pacific between China on the one hand and the US and its allies like Australia on the other. Australia sees the South Pacific as its traditional sphere of influence – Canberra is concerned that China is becoming more established there. That’s one reason why Australia rushed to help Tonga quickly after the volcanic eruption and tsunami. The fact that it uses the largest warship in its fleet for this purpose also has a symbolic character, but this ship is very well suited for disaster relief operations.

In 2016, the Solomon Islands struck a deal with Huawei Marine, a subsidiary of Chinese telecom giant Huawei, with the intention of laying an undersea cable to Australia. However, the Australian government refused Huawei permission to connect the cable in Sydney to the international network.

At that time, the Australian government had just excluded Huawei from expanding its mobile network. Like Washington, Canberra suspects the Chinese government of using Huawei infrastructure for espionage. So that the Solomon Islands could still get fast internet, Australia launched a counter-project, the Coral Sea Cable, which also connects Papua New Guinea with Sydney. The cost was 137 million Australian dollars, around 90 million Swiss francs.

Australia, Japan and the USA jointly finance undersea cables

History is now repeating itself. In December it was announced that Australia, the USA and Japan are financing an undersea cable, which will serve Nauru, Kiribati and the Federated States of Micronesia. This will give around 100,000 people access to high-speed Internet. According to the Reuters news agency Huawei Marine had offered significantly cheaper than European and Japanese competitors in the tender for the project, which had been launched by the World Bank. However, the tender was canceled due to safety concerns.

Washington intervened because it has a decades-old defense treaty with Micronesia. Nauru has close ties with Australia and recognizes Taiwan instead of China. Kiribati, on the other hand, dropped Taipei in 2019 and has recognized Beijing ever since.

There were signs last year that China could expand an airstrip used by the Allies during World War II on a remote island belonging to Kiribati. Alarm bells were ringing in Washington and Canberra because experts suspected that Beijing wanted to build a military base in the South Pacific. Beijing denies having such intentions. But the western allies don’t want to take any risks. They are trying to prevent China from gaining control of vital infrastructure in the South Pacific. This also includes submarine cables.