The art biennale will be firmly in the hands of women this year. But will you really come across female art there? What do you actually expect from art by women?

Cindy Sherman: «Untitled», 2019.

“It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World”: That was in 1966. And the song is still good today. James Brown sang back then that it was men who invented trains and cars – and also the electric light so that we were no longer left in the dark. But he also sang that the world would be nothing without women. Because what would his song be without this second sentence of the refrain: «But it wouldn’t be nothing, nothing without a woman or a girl».

The world needs women. And it’s being celebrated across the art world right now. In many museums and art institutions, the female curators want to return to the feminine in art. However, the current parade of museum presentations by great female artists is long overdue.

From Gabriele Münter and Meret Oppenheim to Kara Walker and Louise Bourgeois to Georgia O’Keeffe, Yoko Ono and Heidi Bucher, the list of exhibitions that are currently being or have been held in Swiss museums by women artists ranges. The Hauser & Wirth Gallery in Zurich is currently showing “Seventy Years of The Second Sex” with artists such as Roni Horn, Zoe Leonard, Cindy Sherman, Eva Hesse and also Louise Bourgeois in dialogue with the French philosopher and pioneering feminist Simone de Beauvoir.

Louise Bourgeois: «Femme Maison», 1994, marble.

Latifa Echakhch is a woman in the Swiss Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. In general, women are the stars of numerous national exhibitions in the Giardini of the lagoon city: the Afro-American artist Simone Leigh has been nominated for the United States pavilion, Maria Eichhorn from Berlin is appearing in the German pavilion, and Sonia Boyce is the artist’s name for the British. The list could be extended almost indefinitely. Venice will be the city of women this year. But what does one expect or hope for from this wealth of female art? And how does art by women differ from male art in the first place?

The little difference

At best, women in art pursue different strategies than their male colleagues, although by no means all of them. In this way, Joan Mitchell had simply asserted herself in the rough environment of American Abstract Expressionism, which was dominated by men – with brute use of the brush. In the dynamic sixties of the American art scene, Eva Hesse consciously resorted to alternative materials such as latex, glass fiber and polyester resin, which were new and perhaps also had feminine connotations in their elasticity and softness.

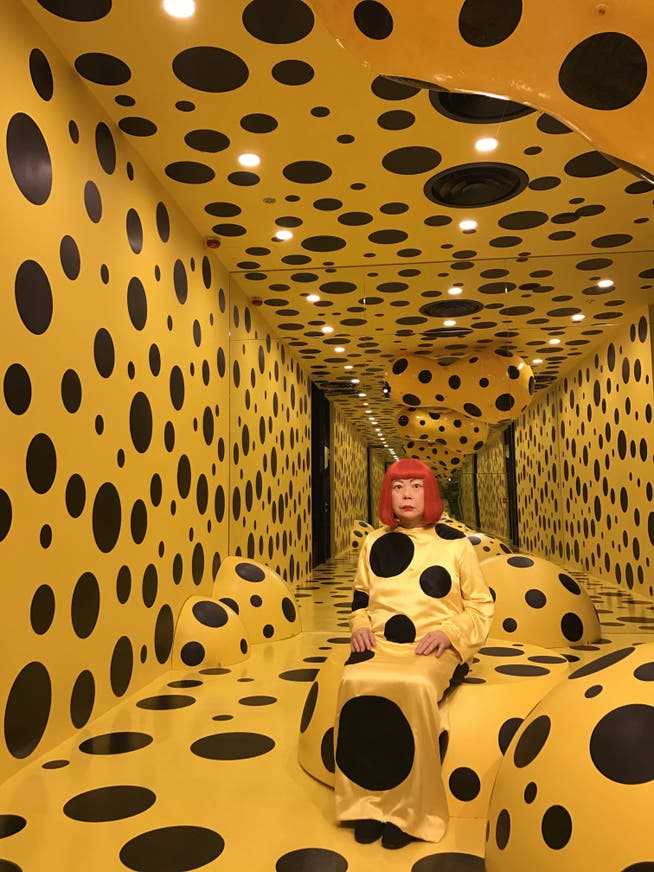

Due to historical limitations in the choice of profession, women also repeatedly used techniques that were traditionally attributed to a female work sphere, such as embroidery, weaving, sewing, and working with textiles in general. Needle, scissors, yarn are still considered feminine attributes, even if it sounds like a cliché. Sophie Taeuber-Arp created geometric works with classic tulle embroidery. Louise Bourgeois and Yayoi Kusama made “soft” sculptures with textile materials.

Wax figure of the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama in an installation with her famous polka dots at Madame Tussauds in Hong Kong.

And sometimes female artists also consciously combine such approaches with feminist concerns. The Egyptian Ghada Amer, for example, criticizes the staging of the female body as a sexual object in her embroidered images of porn depictions. British artist Sarah Lucas uses textile means of expression such as stockings to parody male sexism. And her compatriot Tracey Emin has already embroidered her painful memories of sexual abuse onto white sheets.

When it comes to the female body, art is quickly classified as «female» – or as «male». Classical nude painting, which artists such as Willem de Kooning, Tom Wesselmann and Gerhard Richter have continued to develop since the post-war era, may not be the domain of women. Artists such as the Austrian Maria Lassnig in her painterly body explorations or Valie Export, Carolee Schneemann and the Swiss Milo Moiré with their provocative performances address their own bodies in a very different way.

Maria Lassnig: “Even with Silvia – Silvia Goldsmith and I”, painting, 1972.

Otherwise, however, the difference in art is rather small. The German feminist Alice Schwarzer would probably confirm that. And Simone de Beauvoir doubted that women would remain “special” if only all opportunities were finally opened up to them. On the other hand, she was certain, as she wrote in her epochal work “The Second Sex”, “that the possibilities of women have been suppressed and have been lost to mankind”.

This year’s director of the Biennale, Cecilia Alemani, who is incidentally only the fifth woman to take on this task in the long history of the world art exhibition founded in 1895, is now banking on this lost potential. In the main exhibition that she curated, she reflects, among other things, on great representatives of Surrealism.

Alemani wants to address urgent questions of the time about the threat to our planet. This also includes a new relationship between humans and their environment, animals and plants, but also technology and science, as Alemani announced in a statement. In her exhibition she wants to explore the possibilities of transforming the world, and she apparently sees potential for this in the surrealism of women.

Surreal wisdom

In fact, everything in Leonora Carrington’s paintings seems to be able to change at any time. She painted visions of the merging of humans with the non-human, with animals and the almighty nature, but even of the merging with machines into hybrid beings and the sexes into androgynous beings free from rigid gender roles.

Leonora Carrington: «Self-Portrait, Paintings, 1936-1938.

Another surrealist featured by the Biennale curator is Dorothea Tanning. In her pictures, young women, bare-breasted and wrapped in vegetable clothes, push open doors, knowing that behind every door there are new ones and that the possibilities of imagination are endless. Girls tear down wallpaper from walls and false facades. Their anger erupts in conflagrations from these breaches in the walls, igniting their long, wild hair. It is a women’s revolt that Tanning conjured up in her work.

Leonor Fini, the third of the great Surrealists that Alemani brings to light, celebrates with her matriarchal theater of desire a liberated female sexuality beyond male dominance and long before the sexual revolution, which she as such would probably have criticized in advance by men and for men.

It’s a woman’s world, one would have to sing here, at least as far as the art is concerned. And one begins to fantasize about what the world would be like if it had always been in the hands of women. But beware. Cecilia Alemani is not just about conjuring up lost women’s power that could save the world. Above all, she wants to lift art by women, such as that of the historical positions of Surrealism, out of the shadow of her male colleagues in her exhibition: this is simply because this art is great art.

Venice thus becomes the Città delle Donne. And no man has to fear, as in Federico Fellini’s film of the same name, being swallowed up by man-eating vamps or being mauled by battle-hardened feminists. Because it will hardly be noticed that men’s art is in the minority. Good art actually knows no gender. And since art is no longer a purely male domain, it is more diverse and interesting than ever. Pondering what is female and what is male art is becoming obsolete given the huge diversity in global art production.