After 50 years, Volkswagen has to justify itself to alleged serious human rights violations on its cattle farm in the Amazon. While the car manufacturer in Germany paid compensation to forced laborers from the Nazi era, it has so far refused to take responsibility in Brazil.

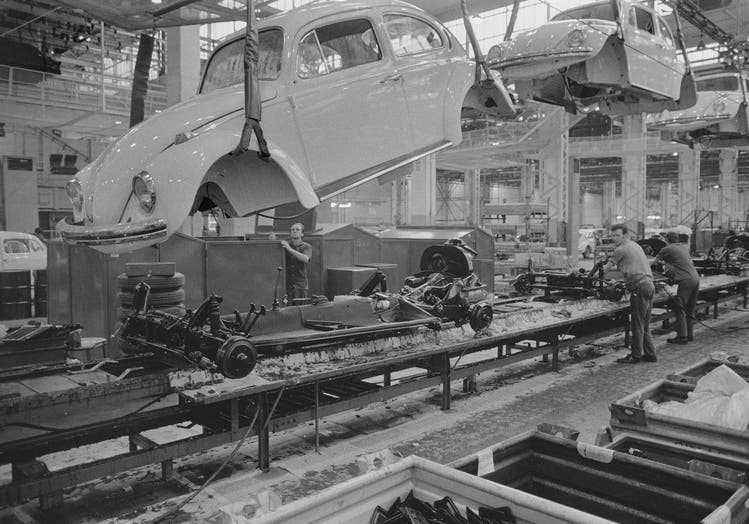

Instead of beetles and VW buses, Volkswagen wanted to make money with cattle in the Amazon. The group planned to export corned beef, frozen meat and meat extract to Europe, the United States and the Middle East.

The fire, which was recorded by NASA satellites over Brazil in December 1975, was one of the largest fires ever recorded in the world. The American space agency warned its colleagues in Brazil that a huge cloud of smoke had been spreading through the atmosphere in South America for weeks.

At that time, a German company was responsible for the ecological catastrophe: Volkswagen do Brasil. This made it known to the public for the first time that the car manufacturer in Brazil operated a gigantic cattle farm in the rainforest – and instead of just selling VW Beetles and buses also wanted to make a profit as a meat producer and exporter in South America. The outrage over the torched Amazon united scientists worldwide in protest for the first time. Volkswagen suffered severe damage to its image.

Not only environmental sins – also human rights violations

But today it is clear that 50 years ago Volkswagen not only committed environmental crimes in the Amazon, but could also be held responsible for serious human rights violations. The group is therefore in the sights of the Brazilian public prosecutor.

Specifically, it is about violations of labor law, which in Brazil are classified as modern slavery, and human trafficking. The public prosecutor summoned the group to Brasilia on June 14th. There she wants to check in an out-of-court hearing whether an agreement between victims in the Amazon and the group is possible. The “Süddeutsche Zeitung” reported on this for the first time this week together with NDR and SWR. Upon request, Volkswagen does not want to comment on the allegations.

The Brazilian Public Prosecutor’s Office for Labor Law has collected evidence and testimonies over the past three years. The decisive factor was a dossier that the anthropology professor Ricardo Rezende Figueira has been collecting for over 40 years. Rezende works at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and is one of the leading experts on slavery and human rights policy in Brazil. Sugarloaf Mountain can be seen through the blinds of his office. During the conversation, he points to four files containing more than 600 pages of material.

The graduate in philosophy and anthropology worked as a priest near the Volkswagen farm from the mid-1970s. In all, he spent 20 years in the Amazon for the Comissão Pastoral da Terra, the left-progressive wing of the Catholic Church. Back in Conceição do Araguaia, he first heard about the inhumane conditions on the Volkswagen farm. “I was surprised that it wasn’t one of the traditional Coroneis, i.e. large landowners, who acted so brutally, but a global corporation from Germany.” He first learned about what was happening on the Cristalino farm from three workers who had managed to leave the farm and seek protection with him as priests.

Volkswagen activities in Brazil began in 1953: it was the first major foreign investment by a German industrial group after the Second World War.

Private security services ran a brutal regime

According to her descriptions, the company used temporary workers on the farm, who were kept like slaves. The estimated 600 to 1200 workers had to pay for their accommodation in makeshift tents, food and transport themselves. They were heavily in debt from the start and were never allowed to leave the farm. Private security services prevented them from doing so. Under their brutal regime, they were punished, imprisoned and shot at. The sick were not treated. Malaria was rampant.

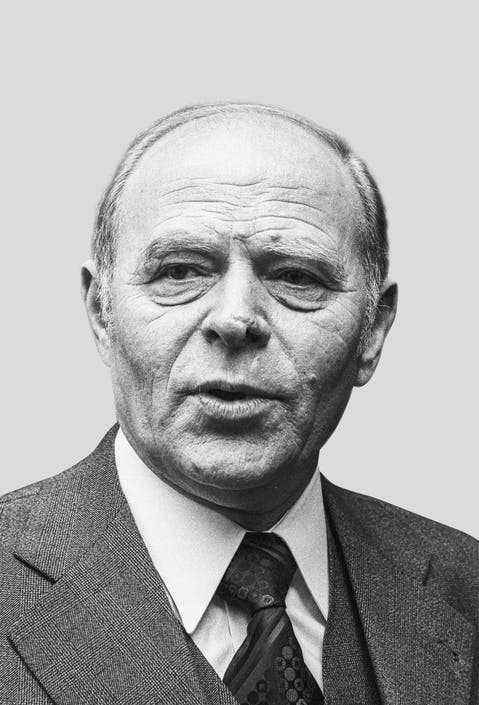

Anthropology professor and priest Ricardo Rezende Figueira

Rezende had the witness statements notarized and collected further evidence. He later visited the farm with parliamentarians from São Paulo and was able to partially confirm the inhumane conditions. For the permanent employees, it was like a perfect model city with a swimming pool, first-aid station, soccer field. The workers’ primitive dwellings were a far cry from the Amazon idyll. But even when journalists reported about it, nothing happened.

It was frustrating that he never managed to hold Volkswagen accountable for human rights violations, says the lively reviewer. But the media, the judiciary, the police, the governments, the bar association and even the trade unions in São Paulo were not interested in what was happening in the Amazon. “We in the church were the only ones who denounced it.”

Rezende heard how those responsible in the VW Group dealt with the allegations, including farm boss Brügger. There were numerous excuses: At that time, all companies acted this way, the company management knew nothing about it, and the responsibility lay with the people who placed the workers. But that, says Rezende, is no justification for injustice committed.

Even when Volkswagen had its unfortunate Nazi history extensively investigated in Germany and finally paid 4.4 billion euros to almost 1.7 million former Nazi forced labourers, the group did not show any similar remorse in Brazil, says Rezende: “They would have here didn’t need to hire a historian in Brazil – we had documented all the evidence.”

They show in detail how Volkswagen increasingly became an accomplice in human rights violations under the military dictatorship in Brazil at the time – and not just in environmental damage.

Tax incentives lured corporations to the Amazon

In the early 1970s, the car manufacturer had by far its most important location outside of Europe in Brazil. VW sold 380,000 vehicles a year there. Almost 60 percent of the market was in the hands of Wolfsburg. Since Volkswagen, like all foreign groups, was only allowed to transfer its profits to Wolfsburg to a very limited extent at the time, the group looked for investment opportunities in Brazil.

Rudolf Leiding, VW boss – first in Brazil, then in Wolfsburg

The then ruling military in turn wanted to settle the untouched Amazon in order to be able to control it better. They feared that guerrilla groups supported by Moscow and Cuba could gather there. Several foreign corporations took advantage of this opportunity: the then computer manufacturer Nixdorf from Germany also invested in an Amazon farm. The US billionaire Daniel Keith Ludwig built up a cellulose production. However, Volkswagen was the only carmaker to embark on the adventure.

This was also due to the fact that Rudolf Leiding, the Volkswagen boss in Wolfsburg, had previously managed the Brazilian subsidiary of Volkswagen for three years. As was usual at the time, he had excellent connections in the highest circles of the dictatorship. Leiding personally gave the order to buy 140,000 hectares of rainforest – before he informed the supervisory board and management board. To head the farm, he appointed Swiss agricultural expert Friedrich Georg Brügger, who, as he boasted to Rezende, had already set up cattle breeding projects in the tropics for the dictators Fidel Castro in Cuba and Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay. VW boss Leiding later justified the decision in front of the board with the words: “The world not only needs cars, but also beef.”

The cattle ranch in the Amazon quickly flopped

But the company Companhia Vale do Rio Cristalino flopped: the Brazilian military first became suspicious because a foreign company controlled huge areas. They tended to trust national companies in the rainforest. In the meantime, nationalist-minded military leaders had taken over the helm in the junta.

In addition, politicians, farmers and other entrepreneurs became jealous because of the high tax concessions to Volkswagen. Even the cattle did not thrive on the pastures as hoped or were stolen. In 1986, after twelve years, Volkswagen was happy to get rid of the farm. The economic damage was limited: the soil had been cheap. VW do Brasil was able to deduct the investments from taxes.

Brazil was Volkswagen’s most important foreign market in 1972. The group supplied almost 60 percent of all cars sold in Brazil.

It all looked as if the world would just forget about Volkswagen’s ill-fated Amazon project and the crimes allegedly committed.

But when Volkswagen in Brazil began investigating human rights violations during the military dictatorship in São Paulo five years ago, Rezende sensed an opportunity to prosecute the group after all. Finally, the VW factory security had demonstrably handed over unionized workers to the security forces of the military dictatorship, although they knew that they would be tortured.

In 2020, Volkswagen paid compensation to former employees, human rights groups and unions: 36 million reais (about 6 million dollars). Volkswagen was thus the first company in Brazil to assume historical responsibility for collaborating with the dictatorship. The events on the Fazenda Cristalino were mentioned in a separate chapter in the final report. But there was never any compensation for workers in the Amazon.

This could change now. And that is also up to prosecutor Christiane Vieira Nogueira. She is co-head of the six-person working group “Rio Cristalino” within the public prosecutor’s office for labor law. Investigators have visited around 20 former workers across Brazil over the past three years and collected evidence of VW’s human rights violations. They have compiled 2000 pages.

“The workers were treated like animals”

Prosecutor Christiane Vieira Nogueira

Like the public prosecutor’s office as a whole, Nogueira has already proven slavery-like working conditions in the supply chain to numerous corporations in Brazil. This also includes international fashion groups such as Zara from Spain or the food group Danone from France. But at Volkswagen, the conditions at the time were particularly shocking. “The workers were treated like animals,” she says in an interview. The fact that such processes could be proven for the first time at a car company is quite unique.