80 years ago, German SS troops shot 335 people, mostly Italians. The massacre in the Ardeatine Caves is now a symbol of the German occupation of the country in World War II. But the process of coming to terms with it only began decades later, initiated by journalists.

The massacre was an act of revenge by the Germans. On March 23, 1944, a total of 34 SS police officers died from a partisan bomb on Via Rasella in Rome. Just one day later, the SS carried out bloody revenge, with the largest single execution of Jewish Italians in World War II. For Italy, the mass murder of 335 people in the Ardeatine Caves is still a day of deep sadness. There isn’t an Italian who doesn’t think of German barbarism when they hear the words Fosse Ardeatine, the karst caves on the Via Ardeatina outside Rome.

In Italy, the massacre is the ultimate symbol of the German occupation of Italy, to which a total of 70,000 civilians fell victim. 20,000 of them were shot in various massacres. Many people did not survive the deportation to Germany, or they died – like the 1,023 Jewish citizens of Rome who were arrested on October 16, 1943 – in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Only 16 of them returned to Rome alive.

This year, German State Minister Claudia Roth is taking part in the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the massacre in Rome. First she visits the site of the atrocity itself, then the ghetto in Rome, where 75 Jewish residents were taken away in order to arrive at the number of 330 Italian victims planned by the SS.

Many Germans are not aware of the inglorious German past in Italy, and many of the places are not familiar either. The largest number of victims – in addition to the Ardeatine Caves – was in the area around the town of Marzabotto near Bologna and the Monte Sole hill group there with 770 deaths between September 29th and October 1st, 1944. The massacre of Sant’Anna di Stazzema took place on August 12, 1944 a total of 394 people died. There was the Fivizzano massacre with around 400 deaths between May and September 1944 and that at Padule di Fucecchio on August 23, 1944, where 174 people were murdered. Added to this are the many victims of the SS in and around Genoa, 249 victims in four different mass shootings of civilians, ordered by the then SS and SD commander Siegrid Friedrich Engel.

SS officer miscounts – more people die

The reason for the massacre in the Ardeatine Caves was a bomb attack by Italian partisans on a unit of the Third SS Police Regiment from Bolzano in the central Via Rasella. They had prepared a handcart with an 18-kilogram bomb and detonated it as they marched past. 34 SS men died, the last one on the morning of the following day, and dozens were injured. It was the largest single loss that the SS had suffered due to a partisan attack in Italy. Two Italian civilians were also killed.

Rome’s SS and SD chief, Obersturmführer Herbert Kappler, organized the revenge operation overnight. For every dead SS man, 10 Italians were supposed to die – at that point there were 33. In the end there were five more because the SS officer in charge “miscounted,” as he would later say. They were “atonement victims” – a Nazi term for innocent victims who had nothing to do with the attack.

To do this, the SS emptied its own prison on Via Tasso of “partisan suspects” and political opponents of the regime and asked Rome’s police chief, Pietro Caruso, to transfer additional victims, normal inmates of the Roman city prison Ara Coeli. The Italian fascist willingly helped the Germans. Anyone who was in the hands of the German occupiers and their Italian helpers was considered a “penitent” for such massacres.

In the end, however, there were still 75 people missing to reach the ordered number of victims. So the SS and Italian police arrested 75 Jews who were “doomed to die anyway.” All the victims were brought into the caves tied up in the early hours of the morning. In order to set a good example for the SS men, Kappler and his senior SS officers Erich Priebke, Karl Hass, Carl-Theodor Schütz and Hans Clemens shot the first groups in the neck with their own hands. After the massacre, the caves were blown up and the victims were only rescued after the liberation of Rome by the Allies on June 5, 1944.

Judgments, but no explanation

Even today, Mussolini nostalgics still have a problem with the active role of the Italian fascists in the massacre. Ignazio Benito La Russa, the President of the Italian Senate and therefore the second highest representative of the Republic, criticized the partisan attack on the SS in 2023 because it was just a “music group of older gentlemen”. The German historian Lutz Klinkhammer called it “a clear falsification of history.” “This police regiment belonged to the SS and was part of the German repressive apparatus during the occupation.”

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni didn’t do any better. She remembered the victims who were murdered “just because they were Italian.” Wrong again: Of the 335 victims, 9 were demonstrably not Italians, but Poles, Ukrainians and 2 Germans. They were not murdered because they were Italian, but because the occupiers viewed them as enemies. But Meloni has a problem: she can’t pronounce the word “fascist” and certainly not “anti-fascist.” After all, she began her political career in the youth organization of the post-fascist MSI.

Some of the perpetrators of the massacre were brought to justice immediately after the war. Police Chief Caruso was sentenced to death for his involvement on September 21, 1944 and was shot a day later. SS officer Kappler was sentenced to life imprisonment in Rome and spent more than two decades in the Gaeta Fortress. In 1977 he managed to escape from the Celio military hospital in Rome and died in Soltau the following year. The SS officer Walter Reder was imprisoned next to Kappler in Gaeta. He was convicted of the Marzabotto massacre and other mass murders. He was the last prisoner to be released in 1985 with a pardon.

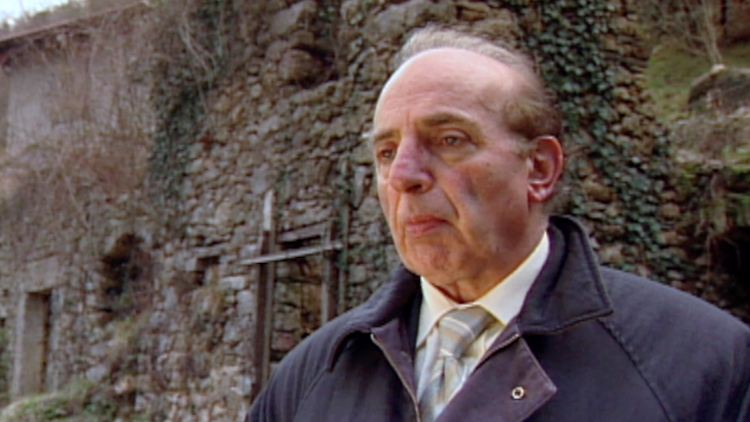

SS Captain Erich Priebke managed to escape in 1946. With the help of the German Catholic Bishop of Rome, Alois Hudal, he reached South America via Genoa. Despite an international arrest warrant that was never lifted, he lived unmolested in Argentina, in Bariloche. He received a pension from Germany, under his real name.

Priebke tracked down in Argentina

Priebke also triggered the intensive investigation into the massacre, but only much later: in 1994, when the American journalist Sam Donaldson tracked him down in Argentina. In the interview, the German openly admitted that he had shot “two or three victims” himself. “It was an order,” he said. He also confessed to having compiled the list of those doomed to death. Because of the hectic pace, he miscounted. Germany allowed his extradition and he was brought to trial in Rome. In 1999, Priebke was sentenced to life imprisonment in Rome; he died in Rome in 2013 at the age of 100.

Priebke’s statements reopened old wounds and stirred up the whole of Italy. It suddenly became clear that the vast majority of massacres between 1943 and 1945 had never been properly investigated. The country had made a political and legal deal with them at the end of the 1950s; in 1961, the Italian military prosecutor’s office closed all cases and they were “provisionally” archived. That was a perversion of the law, because murder does not have a statute of limitations, even in Italy. Only one case – the Caiazzo massacre – was investigated in 1988 after documents emerged. The German Wehrmacht lieutenant Wolfgang Lehnigk-Emden was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1994.

In the same year, after Priebke’s transfer to Rome, the search for the old investigation files began. A mountain of 2,274 folders on war crimes was found, 695 of which concerned murder cases. These files were called the “closet of shame.” They were well known to the authorities, but no one was interested in the unsolved crimes. The folders were sent to the responsible public prosecutor’s offices in Italy, but apart from a trial in Turin in 1999 against Obersturmbannführer Friedrich Siegfried Engel, the investigations made no progress.

The turning point brought another journalistic investigation: On April 11, 2002, an investigative report with interviews from former SS men was broadcast in the ARD magazine “Kontraste”. The RBB journalist René Althammer, the historian Carlo Gentile and the author of this text were involved in the research. A former SS sergeant, Albert Meier, confessed to taking part in the Marzabotto massacre. Former SS Lieutenant Gerhard Sommer also appeared – he would turn out to be one of the main perpetrators of the Sant’Anna di Stazzema massacre.

“We always just wanted justice”

The Italian public did not expect that so many perpetrators were still alive. A few days after the report was broadcast, a new public prosecutor in La Spezia, Marco de Paolis, took over the investigation. As of 2004, around 80 people responsible for many of the massacres in Italy were brought to justice. “We never wanted revenge, we always just wanted justice for our loved ones,” said Enio Mancini, one of the survivors of Sant’Anna.

This came about from the report “Perpetrator Project” by historian Gentile and the author of this article. The project deals with the biographies of the perpetrators – and searched for them. Today new questions arise: How does one become a mass murderer? What drives these people? What causes people to torture and kill civilians? Questions that have become relevant again in light of Russian war crimes in Ukraine and the Hamas massacre of Israeli civilians on October 7, 2023.

“We know from the biographies of the perpetrators in Italy that the vast majority of these people are not ‘monsters’, but rather people from the middle of society,” says Gentile. “Many of the high-ranking perpetrators even had academic humanistic training; after the war, some became involved in politics; no one had any idea of their involvement in the murder of mostly women, children and defenseless people.”

The number of accomplices in the massacres is also shockingly high. A total of around 600,000 German soldiers from the Wehrmacht, SS, Air Force and Navy were deployed in Italy between 1943 and 1945. “Of these, around five percent took part in the massacres and their units were directly involved in the murder of around 10,000 civilians,” says Gentile. 30,000 Germans either took part directly in the massacres or at least knew what their units had done. A similar number of Italian soldiers committed massacres against their own countrymen and in other countries. No wonder that in Italy, as in post-war Germany, people wanted to “draw a line” under war crimes. The fact that the victims of the massacre in the Ardeatine Caves are being remembered today is a good sign. Even if the processing took a long time.