The historical direct train from St. Gallen to Paris is the epitome of the former importance of Eastern Switzerland. But the story has a catch.

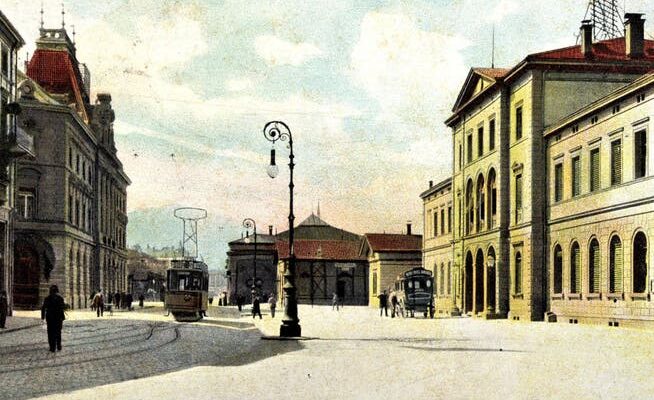

Fierce competition: the St. Gallen station square with the old station building in 1896.

When St. Gallen celebrities talk about the glorious history of their homeland, Paris is not far. The reference to the direct train connection between St. Gallen and the French capital, which is said to have existed up to 100 years ago, is an integral part of the Eastern Swiss narrative.

The railway line regularly appears in speeches and commemorative publications, from the government councilor to the director of the Chamber of Industry and Commerce. St. Gallen institutions and organizations also like to advertise with the historic railway line. The St. Gallen cultural center Lokremise writes on its website: “Its Art Nouveau façade is reminiscent of the heyday of the textile industry in Eastern Switzerland and of the direct train connections with Paris.”

The location promotion of the city of St. Gallen lists them among the “ten amazing facts about the Gallus city”: “Crazy: Up until a little over 100 years ago there was a direct train connection between St. Gallen and Paris without stopping in Zurich.” And the Südwestbahn (SOB) uses the legend to advertise a visit to the St. Gallen Textile Museum: “Trains run non-stop to Paris, American merchants flock to the city: the world is looking to St. Gallen.” This connection has also been mentioned in the NZZ, most recently last autumn in an analysis of Eastern Swiss identity.

«Nice blossoms and pithy slogans»

Only: The beautiful story has a catch: It is not proven. To date, not a single timetable has been found in the relevant archives that lists a direct train connection from St. Gallen to Paris. “Even in brochures with international connections or correspondence, we could not find any reference to such a direct connection, it always seemed necessary to change trains in Zurich or Basel,” says SBB Historic, the foundation for the historical heritage of the federal railways.

The state archives have not found a single piece of evidence for the connection to date. «The Paris–St. Gallen is known as a legend in the local historian scene, »it says on request.

The St. Gallen Textile Museum has also already carried out research into this “ominous direct connection from St. Gallen to Paris”, as the museum librarian Deborah Messerli puts it. No reliable evidence was found. “The version that tells of a connection without stopping in Zurich is very common here,” says Messerli. “We have to assume that these stories are not true.”

The St. Gallen publicist Anton Heer is one of the best experts on the history of railways in Eastern Switzerland. He never found any evidence of the alleged direct connection between St. Gallen and Paris. “In the 19th century, railroad fever led to nice blossoms or pithy buzzwords,” he says.

He sees a possible explanation in the mostly storm-related detours of the Orient Express via St. Gallen. Before the Second World War, the historic railway line from Istanbul to Paris was temporarily routed via Arlberg and Zurich. In the event of avalanches and floods, the train was diverted via St. Gallen. “The most drastic was the Rhine disaster in 1927. At that time, parts of the Rhine embankment and the railway embankment near Schaan disappeared.”

The fact that the textile industry in Eastern Switzerland was of outstanding importance at the time is historically undisputed. Between 1870 and 1910, the number of people employed in the textile sector increased from 2,300 to 11,800 in the St. Gallen region alone, as Anne-Marie Dubler writes in the “Historical Lexicon of Switzerland” (HLS). During the same period, the sector grew from 46,100 to 87,600 employees in the four eastern Swiss cantons of St. Gallen, Thurgau, Appenzell Innerrhoden and Ausserrhoden. Around 1910, embroidery, accounting for 18 percent of total exports, became the most important export branch of the Swiss economy.

Great expectations for the future

In fact, however, the international routes Zurich–St. Gallen–Lindau or Zurich–St. Gallen-Innsbruck not exceptionally well served even between 1870 and 1914, prosperous textile industry or not. From 1872 onwards, the Vorarlbergerbahn had a certain importance for St. Gallen because of the Rhine crossings at St. Margrethen and Buchs. The Arlberg Railway did not follow until 1884. The people of Eastern Switzerland were also involved in the now-forgotten Lake Constance Belt Railway from St. Margrethen via Bregenz to Lindau.

However, Zurich-Munich was routed via Romanshorn-Lindau until around 1900. “If you talk about international connections, then before 1900 a daily pair of trains was already an achievement,” notes railway expert Heer. So if you wanted to get from St. Gallen to Paris, you had to travel via Zurich, Basel or Geneva. From there there were direct connections to Paris.

In general, St. Gallen only played a subordinate role in the Swiss rail network for a long time. The largest railway company, the Schweizerische Nordostbahn (NOB), founded in 1853, was primarily interested in the Zurich–Romanshorn connection. At that time, St. Gallen was the headquarters of the United Swiss Railways (VSB), but for the connection to the economic center of Zurich, the VSB only had a right of joint use for the NOB line Wallisellen–Zurich.

In other words: The competition between the Swiss railways in the 19th century did not necessarily lead to better connections – and certainly did not lead to the realization of non-transfer routes across Switzerland and abroad. “The railways involved fought fierce competition – not for the benefit of the customer,” says Heer.

Heer sees another explanation for the St. Gallen-Paris myth in the innumerable visions of the railway fever in the 19th century. At that time, Winterthur played an important role, for example for the east-west route bypassing Zurich – and indeed also for the Winterthur-Paris line via Bülach and Koblenz.

The St. Gallen station building, built in 1913 and designed by the architect Alexander von Senger in the style of a cathedral, is evidence that the people of eastern Switzerland had great expectations of the future. Achievements such as the Bodensee-Toggenburg-Bahn and the Rickenbahn, both of which opened in 1910, can be traced back to the optimistic progress of those years. It is understandable that the St. Gallen textile industry also dreamed of a direct connection to Paris.