I promise not to use expressions like “counter-sales” or “out of order” in this article. It is said. We are therefore going to address in the lines that follow a curious paradox: why an industry with immense barriers to entry and in oligopoly finds itself caught in a perfect storm, both on the side of the turbine manufacturers (Vestas, Siemens Gamesa, General Electric) than at the developer level (Orsted in the lead)? Three main reasons can be put forward for this situation.

For a year, the sector has been struggling

First of all, the sector is facing spectacular inflation in its production costs. Whether in terms of raw materials, transport, energy or construction. We also find there all the contradiction of an activity concentrated on renewable energy: its carbon footprint is calamitous because of a transcontinental supply chain and the resources necessary for the construction of a wind turbine in terms of concrete , metals and minerals.

The second reason for sectoral difficulties is due to the increasingly assertive maturity of major contractors which are essentially the energy majors, such as BP Plc, Shell or Equinor. These giants are converting to renewables, because they are the best placed to ensure the development of the sector by reinvesting the oil and gas revenue in the greening of activities. These fastidious customers have long since become masters in the art of integrating hypercomplex logistics chains to negotiate the best prices with suppliers: after the beginnings linked to the emergence of the sector, they are now in a position of strength in the face of offshore developers and turbine builders.

Onshore wind turbines (Source Vestas)

Finally, the third explanation of the current difficulties, the inevitable Chinese competitors, which are increasingly sophisticated and are now able to manage megaprojects themselves in Asia, the world’s largest market for this. In the wind industry as in the others, European players have enslaved themselves to win juicy contracts in China, in exchange for sharing their know-how. And by a boomerang effect already seen, Chinese manufacturers are now competing with Western producers with more competitive costs. This competition will cost Europeans market share in Asia, but protectionist policies in Europe and the United States should enable them to maintain solid positions in the West. The media specializing in renewables Recharge estimates that a Chinese-made wind turbine costs up to 50% less than its European counterpart. In offshore, pre-delivery costs would be around 850,000 to 1,350,000 USD per MW for Western producers compared to around 550,000 USD per MW for their Chinese competitors. The latter are now capable of producing turbines as powerful as their rivals, both onshore and offshore. Listed Chinese companies in the sector include Xinjiang Goldwind Science & Technology and Zhejiang Windey.

It emerges from these three elements that the European sector is in a severe “squeeze” position: with customers, contracts are signed for the very long term on a cost basis generally estimated aggressively (to win the auctions), so when costs explode… the increases are 100% borne by the turbine manufacturers. And at the stock market level, the accumulation of bad news has radically changed the market’s perception of the sector. For a long time, investors remained hypnotized by the narrative without paying enough attention to the real financial dynamics. But the fact that demand is no longer a problem for decades does not necessarily mean prosperity.

Practical cases

So let’s look at these financial dynamics. Starting with the long 2011-2021 cycle, since it was exceptionally buoyant for the sector, which benefited from ultra-favorable financing conditions and low energy and raw material costs.

At Vestas, turnover has tripled, but margins are unstable and cash generation very uneven due to the capital-intensive business and large variations in working capital requirements. Same dynamic at the German Nordex. Revenues quintupled but results remained under pressure. As for Siemens Gamesa, the situation is much more critical: management failures accumulate with poorly calibrated prices and a non-optimized cost structure. So much so that Siemens Energy announced in May the takeover of minority shareholders and the withdrawal of its subsidiary from the rating, just to take it back in hand vigorously out of sight.

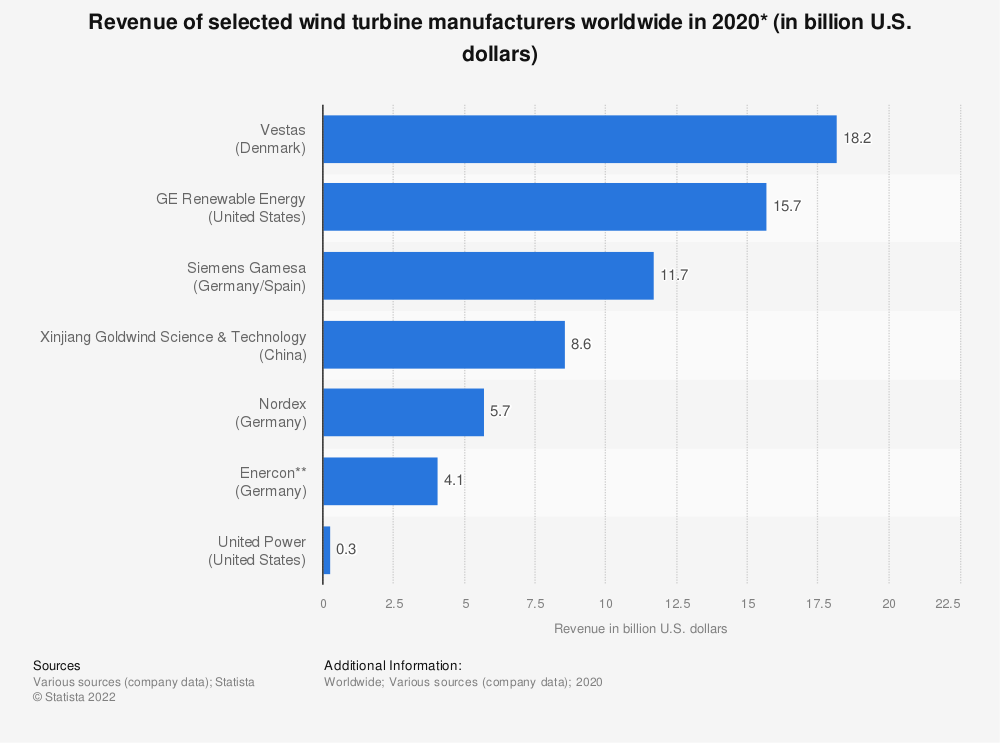

The 2020 revenues of the main players in the sector (Source Statista)

For these three files, the precedent of gas turbines does not really inspire confidence. As a reminder, this highly strategic sector, dominated by a small number of players (Alstom, Siemens and General Electric in particular in their time), has never really made money. The pricing power was weak, the dynamic very cyclical and the activity hyper-capital intensive. It’s a dangerous cocktail. Often fatal.

Orsted’s profile is different. The Dane is on the other side of the fence: he develops offshore fields but does not build turbines. Its growth is weak over the long cycle, but in return its margins are relatively preserved. It must be debited with accounts that are difficult to read with payments indexed to the quantity of energy produced by the developed fields. And acquisitions which for the moment are struggling to create value. In addition, predicting future results is a rather complicated exercise. Energy production is of course linked to the quantity of winds, estimated on historical weather statistical models. But lately the wind is blowing less than expected and therefore the payments are lower.

The situation that the sector is currently going through is more a normalization than a real panic. One could speak of a return to the sobriety of investors who are no longer hypnotized by the renewable narrative. And even after the recent correction, the sector does not offer very solid guarantees when it comes to investments.