For a long time, the Lars von Trier case divided cinephilia into two irreconcilable camps, pro and anti, launched into an aesthetic “war of position”. When some cried genius, others uttered cries of horror. And then, in May 2011, something shifted, following the presentation at the Cannes Film Festival of Melancholia, his twelfth feature film. The apotheotic conclusion on the collision of the stars remonstrated with the most recalcitrant, who could no longer suspect that the filmmaker was a common joker, at the very moment when he was scuttling himself at a press conference with remarks that were, to say the least, nimble on Nazism.

Perhaps it then appeared that the dimension of self-sabotage was inherent to the art of Lars von Trier, each of his films secreting beneath its monumental exterior its own antidote of buffoonery, in a labyrinth of broken lines, of violent contradictions , which does not prevent emotion from making its way.

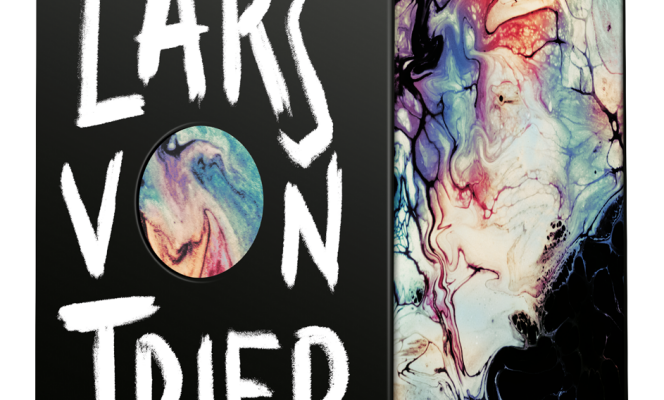

The complete box set that Potemkin devotes to the Danish mad scientist, bringing together his fourteen feature films in restored copies, among a deluge of supplements, is a model of the genre, the equivalent of an edition of “La Pléiade”: an entire work contained in an elegant black cube (the only thing missing is the television series The Kingdom). All that remains is to walk there to see again, for example, his beginnings as a frenzied formalist, with the dark phantasmagorias ofElement of Crime (1984), police investigation in an underground Europe lit as if under a sodium lamp, or evenEurope (1991), a black-and-red trip through haunted and devastated post-war Germany.

Paranoid aestheticism

We will also refer to his “Dogma” turn (named after the artistic manifesto he launched in 1995 with Thomas Vinterberg), and which will give birth to his great twisted melodramas: Breaking the Waves (1996), where the gift of self takes the form of a perverse eroticism, then Dancing in the Dark (2000), with the singer Björk and her formidable musical compositions, which accompany the candid martyrdom of a worker in America, crushed by the system. Both electrified by the jolts of a panting handheld camera and the jump cut wild of a “emotional montage” (as said in an audio commentary with editor Anders Refn).

We will then see the work move towards abstraction, as in Dogville (2003) where a small American town, of which Nicole Kidman becomes the scapegoat during the Great Depression, is modeled in white lines drawn on a large black board. Then little by little towards a paranoid aestheticism, notably with Antichrist (2009) which replayed the couple’s crisis for us in a gore-panic version, or the great mental frescoes of Nymph()maniac (2013) and The House That Jack Built (2018), which would be measured against the Fine Arts by mire and triviality.

You have 15% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.