100 years assassination attempt on Rathenau

When the Consul organization destroyed hope for peace

06/24/2022, 06:51 am

Only in the right-wing extremist scene did the rhyme circulate: “Blast Walter Rathenau, the goddamn Jew!” Finally, on June 24, 1922, right-wing extremists assassinate the foreign minister. The question arose then – and still does today: how resilient is German democracy?

Even without social media, the terrible news spread rapidly in Berlin on June 24, 1922: Walther Rathenau, Reich Foreign Minister, had been murdered. The beacon of hope of the young republic. It is precisely this hope that the conspirators of the right-wing organization Consul want to destroy with the attack. Their goal: bring down the Weimar Republic, which they hate, and set up a military dictatorship.

But in the early summer of 1922 – three and a half years after the loss of the First World War – the first all-German democracy was shaken. SPD and Co. initially moved closer together as a reaction. The historian Heinrich August Winkler calls the assassination attempt on the Jews in Rathenau a “Human sign”, i.e. a sign of impending disaster. Almost eleven years later, Hitler came to power.

Experts keep asking the anxious questions of whether Weimar can happen again and how fragile German democracy is. There is no acute danger, after all, Germany is one of the most stable democracies in the western world, they say. But the Germans shouldn’t be too sure, says Freiburg history professor Jörn Leonhard: “What, despite all the differences, is reminiscent of the 1920s and 1930s from afar is this feeling of profound insecurity, of the sudden lack of certainty of expectation, is the idea that the Stress test for the resilience of the democracies could still be pending.” Greetings from the Ukraine war.

Nine shots from the submachine gun: the assassination in Grunewald

Flashback: Walther Rathenau, son and heir of the founder of the General Electricity Company (AEG), lives in a stately villa in Berlin-Grunewald, just a few minutes’ drive from Kurfürstendamm. June 24 is a Saturday, Rathenau is being chauffeured from his house to the Foreign Office in an open car when, at around 10:45 a.m., a Mercedes overtakes the minister’s car and a man fires nine shots at him with a submachine gun.

The Berlin historian Martin Sabrow has meticulously reconstructed the course of the assassination. “The foreign minister, leaning on a stick and smoking a cigar, was apparently completely taken by surprise by the attack.” He had sent away the bodyguards – despite countless death threats. For a long time, the rhyme had been circulating in the right-wing extremist scene: “Blast Walter Rathenau, the goddamn Jew!” The 54-year-old Rathenau died a few minutes after the attack.

Since 1918 right-wing radicals have been drawing a trail of blood through the republic. Almost 400 political murders are counted up to 1922. The victims include Rosa Luxemburg, the SPD man and signatory of the Treaty of Versailles, Matthias Erzberger, and the Bavarian Prime Minister Kurt Eisner. “In this period, up until at least 1923, many Germans questioned whether the state was strong enough to enforce its monopoly on the use of force so consistently as to prevent a civil war,” says historian Leonhard. Even if the right-wing terrorists’ plan didn’t work out, the murder shows “how contempt for political personnel weighed on Weimar’s political culture and profoundly polarized post-war German society.”

Man of contradictions: Rathenau tends to change positions

The publicist Sebastian Haffner wrote in the late 1970s: “Rathenau and Hitler were the two phenomena that stimulated the imagination of the German masses: one through his incomprehensible culture, the other through his incomprehensible meanness.”

After the signing of the German-Russian Treaty of Rapallo in April 1922, the conservative politician and Jew Rathenau came under increasing criticism.

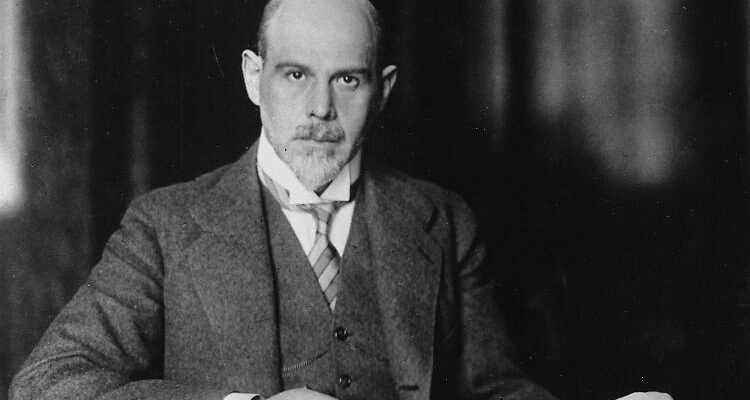

(Photo: ASSOCIATED PRESS)

Who is this Rathenau? A man of contradictions. Industrialist and intellectual, a Jew barred from becoming an officer. A big capitalist who goes to the left-liberal DDP after the war. A driven man looking for a place in German society. Organizes supplies efficiently during the war, pushes for a “victorious peace”. Later defamed from the right as a “fulfillment politician” because he tries to soften the harsh reparation conditions through close cooperation with the victorious powers. Is skeptical about a rapprochement with communist Russia, but signs the Treaty of Rapallo with the other loser in the war in April 1922, which irritates the western powers.

His charisma makes him an object of hatred for the right-wing

And yet: for many Germans at the time, Rathenau embodied the hope for peace, for cooperation with England and France, for the resurgence of the Reich. And: “The possibility that after years of war, uncertainty, soup kitchens and hyperinflation everything would be fine after all,” writes journalist Thomas Hüetlin. It was precisely because of this radiance that the Consul organization wanted to get rid of him.

The historian Leonhard believes that some of the very strong attributions after 1945 have to do with Rathenau’s role as a “martyr of the young republic”. It is undisputed that Rathenau could have played a very important role. “But recognizing his merits must not lead to ironing out the contradictions in his personality.”

Parallels from Rathenau to Lübcke?

From Rathenau to Lübcke: Are there parallels? What is the lesson from this period? There is no easy learning from history, experts agree. “Unlike in the Weimar Republic, the constitution and the parliamentary system based on it enjoy broad social, political and institutional support,” writes Winkler in the “FAZ”.

But: “The Bonn Republic also experienced political extremism, which escalated to the point of organized murderous actions, primarily on the part of the extreme anti-capitalist left in the form of the RAF.” He is reminiscent of the “Murder Center” of the NSU, which from his point of view resembled the Consul organization in some ways. And: “As the murder of the Kassel district president Walter Lübcke on June 1, 2019 shows, Germany cannot be sure today that the network of the NSU will not continue to exist in a different form or arise again and individual perpetrators like the racist murderers of Halle and Hanau inspired.”