The judges will consider the copyright legislation on Wednesday. The case concerns a set of images that Andy Warhol based on a 1981 photo of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith.

A touch of pop will brighten up the very serious Supreme Court of the United States on Wednesday, October 12, responsible for deciding whether Andy Warhol could use a photo of Prince in his work without paying royalties to the author of the photo.

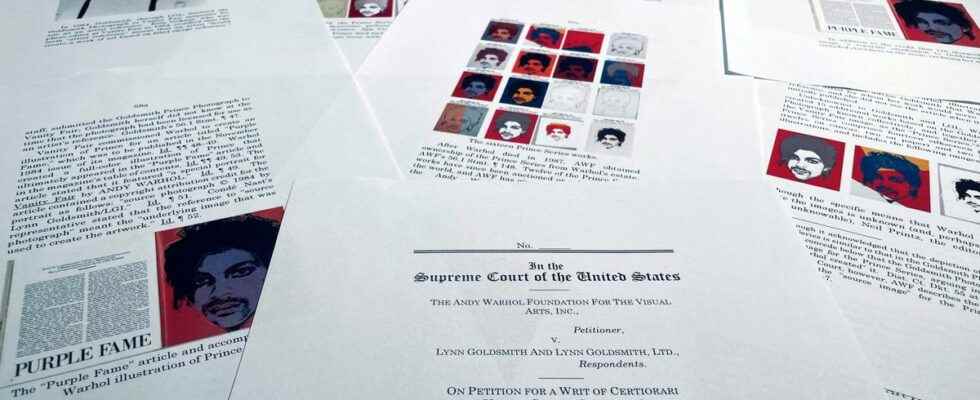

At the heart of the conflict: sixteen screen-printed portraits made in 1984 by the “pop art pope” from a photo of the legendary musician taken three years earlier by Lynn Goldsmith. The photographer, known for having immortalized several rock stars, requests copyright from the Andy Warhol Foundation, which refuses it. After contradictory court decisions, the Supreme Court must now decide between them. It will take advantage of this to clarify intellectual property law in terms of so-called “transformative” works, that is to say works that borrow from a first work to lead to an original creation.

The affair finds its source in 1981. Lynn Goldsmith proposes to the weekly Newsweek to draw the portrait of a musician who begins to break through. She takes several black and white shots of the young man with fine features. In 1984, the album Purple Rain propels Prince to stardom. The magazine Vanity Fair wants to devote an article to him and asks Andy Warhol to paint his portrait in the style of his famous colored engravings of Marilyn Monroe or Mao. For 400 dollars, Lynn Goldsmith authorizes the magazine to use one of her photos for the exclusive use of this article. Entitled “Purple Fame”, the text is accompanied by Prince’s face, purple skin and jet-black hair, which is silhouetted against a bright orange background. The caption credits both the artist and the photographer.

SEE ALSO – A portrait of Marilyn Monroe painted by Andy Warhol sold for 195 million dollars at auction, a record

Not done enough “add or change”

The story would have ended there, if Andy Warhol had not declined this photo in all tones to create a series of 16 portraits of the musician, whom he admired for his talent and his androgynous style. Lynn Goldsmith discovered their existence in 2016 when Prince died, when Vanity Fair published on the front page an image of the “Kid of Minneapolis” taken from his photo but all orange this time. She then contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation, which has managed the artist’s collection since his death in 1987 and had received $10,250 for this publication. The foundation immediately took legal action to have its exclusive rights to the series recognized. The photographer counterattacked.

A trial judge ruled in favor of the foundation, finding that Andy Warhol had transformed the message of the work. For him, Lynn Goldsmith focused on showing Prince as a person “vulnerable, uncomfortable”while the portraits of Andy Warhol underline his status as“icon, larger than life”. An appeals court, however, invalidated his reasoning, finding that the judges could not play “art critics and analyze the intentions and messages of the works”, and had to content themselves with evaluating the visual similarities between the works. According to his decision, Andy Warhol did not “addition or modification” enough to owe Mrs. Goldsmith nothing.

There can’t be one rule for purple screen prints and another for orange ones

The foundation then turned to the Supreme Court, asking it to reject the“unbelievable” request from Lynn Goldsmith. Photographer “wants the Court to declare the work of Andy Warhol – who is universally recognized as a 20th century genius behind the Pop Art movement – non-transformative and therefore illegal”, strangle his lawyers in a statement sent to the high court. But she doesn’t see it that way. Her argument recalls that she was paid and credited in 1984 and not in 2016. “Intellectual property law cannot have one rule for purple screen prints and another for oranges”note its representatives.

The nine sages of the Court will therefore have to say whether a work is “transformative” because it conveys a different message from its source, or because it is visually different. His answer, expected by June 30, will have serious consequences for the art world which, like the American courts, is divided on the answer to be given.