For a long time I knew little about Arthur Bloch. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I found the courage to consciously confront his fate. Eighty years ago my great-grandfather was brutally murdered because he was Jewish – here in Switzerland. This is his story.

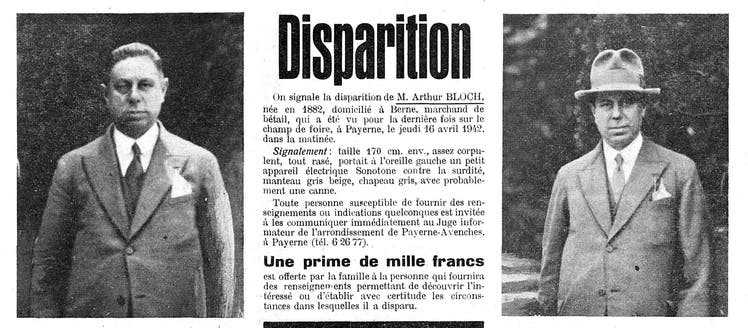

Arthur Bloch’s missing persons report, printed in the newspaper “Le Démocrate” on April 22, 1942.

I don’t know when I first heard about Arthur Bloch. My mother rarely spoke of him. When she spoke of him, she spoke briefly and in a woodcut-like manner, mainly describing the events surrounding his violent death. She mentioned a mutilated body, a bloody milk can, a lake from the bottom of which human bones had been recovered. Then she fell silent again. Years passed before she mentioned her grandfather’s name again.

Arthur Bloch’s story lay like a whisper over my childhood, ever present but intangible. I knew too little about my great-grandfather for his death to make sense to me, too much for me to forget. I often lay awake in bed imagining the milk can in which his remains had been disposed of. I was particularly concerned with the size and shape of the container. Because I had never laid eyes on a milk churn that could fit an adult’s body.

I pondered this oddity for hours. Hours without reflecting on how horrible this crime had been. How horrible that my great-grandfather had to die just because he was Jewish. A Jew in Switzerland.

Many years passed before I found the courage to consciously deal with Arthur Bloch’s fate. Like missing pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, more details about his life and death came to me. For example, I found out that he had been a passionate cattle dealer. That he had lived in Bern with his wife and two daughters. That he had been a big, burly man. That he’d ended up in three milk cans, not just one.

A gift to Hitler

It is April 1942. War is raging in Europe. Just three months earlier, the systematic annihilation of the Jewish population had been sealed at the Wannsee Conference. Switzerland is surrounded by the Axis powers, and the atmosphere in the country is tense. Jews in Switzerland try to flee overseas. If you don’t succeed, persevere.

Some voices in this country long for the connection to the German Reich. So also a frontist group in Vaud. However, the Swiss Nazis did not want to wait any longer until the German troops invaded. One must finally take action, kill Jews. The first is said to be a gift to Adolf Hitler for his 53rd birthday.

Myria Bloch has a bad feeling on April 16th. Nevertheless, that morning her husband Arthur takes the train from Bern to Payerne, where he regularly trades at the local cattle market. It should have been the last time.

In the late morning, two young men approached him on the Payerne market square. They pretend to want to sell him a cow. Arthur Bloch unsuspectingly follows them through the narrow streets to a remote barn. There are more accomplices lurking there. He is hit from behind with an iron bar. The burly man lies gasping on the ground, gasping for air. Until a revolver is pressed to his temple. The bullet shatters his skull.

Now the corpse has to go. Knives are fetched, an ax. First, Arthur Bloch’s throat is slit. A lot of blood flows. Then the head is completely severed from the torso, then the arms and legs. Finally the torso is split lengthwise. The mutilated body parts are crammed into milk cans. In the first, the legs land. In the second half the torso, the arms and the head. The third pot is filled with the other part of the body, with lungs and heart.

The murderers transport the bloody containers to Lake Neuchâtel by car. There they are pushed off a jetty into the water and drowned. Arthur Bloch is just 60 years old.

“God knows why”

On the day of the murder, my grandmother Liliane was already living in Zurich, where she was completing an apprenticeship as a seamstress. When her mother Myria informs her that Arthur is absent that evening, she takes the next train to Bern. The police are alerted and a missing persons report is filed. After that the waiting begins.

Various false reports came in over the next few days: someone believed to have sighted Arthur Bloch in the Râpaz forest, someone else in Lausanne, someone else in Paris holding hands with an unknown woman. The uncertainty makes the bereaved sick. Myria doesn’t eat anymore. It takes eight days for Arthur Bloch’s remains to be recovered from Lake Neuchâtel.

On April 27, 1942, Arthur Bloch, or what was left of him, was buried. The Jewish population in Switzerland mourns. However, Myria does not have the strength to attend her husband’s funeral.

Over the coming months, Myria’s health steadily deteriorated. She suffers from severe depression, along with anxiety, obsessive-compulsive thoughts and insomnia. A year after Arthur’s burial, helpless and desperate, she had a tombstone set on which, contrary to local Jewish tradition, an epitaph was engraved. The black stone slab reads: “God knows why”.

After that, Myria will leave Bern. A short time later she was diagnosed with cancer. Only five years after her husband’s murder, my great-grandmother is dead. She will be fifty-four.

A family wound

My grandmother Liliane is in her mid-twenties when she has already lost both of her parents. Struggling to get over the blows of fate, she stays in Zurich and tries to start a new life there. She marries, raises children. But they are plagued by anxiety throughout their lives.

She is repeatedly plagued by uncontrollable crying spasms, for example when my mother doesn’t come home from school on time. Liliane always has to know exactly where her daughter is, making exuberant phone calls to inquire whether she is healthy, whether she is still alive. Until the cancer eats away at her body too. My grandmother is fifty-six years old. I never knew her.

What I do know, however, are the phone calls. Because my mother always had to be in the picture about the well-being of her children. As a teenager, it would never have crossed my mind to come home from a party even a minute late. Because I knew what a panic I would have put my mother in. I was often annoyed by this narrow-mindedness. I couldn’t understand at the time that this trait was directly connected to Arthur Bloch’s death.

Today I understand. The realization helped me to get closer to my mother, but also to myself. Because even if it was difficult for me to admit it to myself for a long time: Similar fears also lie dormant in me.

A part of Swiss history

Arthur Bloch’s fate is and will always be a part of my story. However, it also remains part of Swiss history. Yet hardly anyone talks about it. There is no monument to Arthur Bloch. Nothing reminds of his terrible death. But nothing to his life either.

Arthur Bloch was born in 1882 in the canton of Bern and grew up there. He was proud to be Swiss. Only ten years before he was born, his father had acquired citizenship and was therefore one of the first Jews to be naturalized in Switzerland. At the military levy, Arthur was assigned to the dragoons of the Swiss Army. He enthusiastically completed his military service, where he lost the hearing in his left ear in an accident. In 1916 he took over his uncle’s cattle business. He married a Jewish woman and raised two Jewish children.

When war broke out and the persecution of the Jews in Europe became ever more evident, part of his extended family decided to emigrate to America. Arthur also considered emigration. But as frightening as the threat was, Arthur didn’t want to turn his back on Switzerland. He loved his homeland too much.

I don’t know much more about my great-grandfather. Not much more can be learned from the isolated books that have been written about his fate.

What my family is left with today is a fragmented memory of Arthur Bloch. As well as some photos. One shows him on the market square, maybe in Payerne, maybe somewhere else. Dense treetops hang above him. Cows and horses can be seen in the background. My great-grandfather wears a hat and suit and smiles shyly at the camera.