Dmitry Medvedev is stuck in the sidelines of Russian politics. Now he’s using the war in Ukraine to step out of cover and raise his profile. His behavior also stands for the dramatic change in Russia.

At the top, but never quite in power: Dmitry Medvedev was President and Prime Minister of Russia – and always in the service of Vladimir Putin.

Special times sometimes create unexpected careers. Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s president from 2008 to 2012 and then prime minister until 2020, seemed to be forgotten in the post of deputy chairman of the Security Council created especially for him. Suddenly, however, Vladimir Putin’s long-time companion draws attention to himself almost every day with outpourings in his Telegram channel. State media are recording his comments on what is happening. He has become one of the loudest voices of the “Party of War” in Russia – those adepts of Putin who often go even further in their choice of words than the president.

Drastic suggestions and taunts

Just a few days after Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, Medvedev was thinking aloud about the benefits that leaving the Council of Europe would have for Russia. Among other things, he mentions the possibility of reintroducing the death penalty. He picks up bits and pieces of anti-Ukrainian propaganda, such as the alleged anti-Russian US biological laboratories in the neighboring country. He compares the West’s sanctions to the Inquisition and repeatedly emphasizes how much the West is harming itself by doing so.

Everyone is allowed to criticize the state and the government, which is undoubtedly part of democracy, he told journalists from the state news agency Ria in an interview. But to oppose the state in times of “war or a special operation” is not acceptable. He even more condemns those who have left the country and wish for Russia’s defeat. That is sheer treason. And when the German Bundestag agrees to the delivery of heavy weapons to Ukraine, it compares it to the Reichstag during the Nazi era. His warmongering is usually worded a little less vulgarly than that of the propagandists on state television, but nevertheless mostly derogatory, sometimes insulting, often crazy in content and tone.

Medvedev as an apologist for the war and agitator against the West – this change is remarkable, at least at first sight. It is also an allegory of the drastic changes in Russia caused by the Russian war against Ukraine.

Once hope for political awakening

Although Medvedev was always seen only as the deputy of his political foster father, Putin, from 2008 many Russians, including those in the elite, linked the young-looking lawyer from St. Petersburg with the hope of a political awakening. To be sure, this was a naïve idea from the start in many respects; after all, the often awkward-looking functionary owed his career in politics solely to his obsequious loyalty to his superiors in the St. Petersburg city administration.

After Putin’s (left) return to the Kremlin in 2012, Medvedev becomes prime minister. In the early days after the role reversal, the two occasionally appeared at what appeared to be staged informal meetings.

But during his tenure, Medvedev coined sentences that had not previously been heard from the Kremlin – “Freedom is better than bondage,” for example. He wanted to modernize Russia’s economy and took Silicon Valley as a model. His love of primarily American electronic gadgets brought him some ridicule, but at the same time marked the greatest possible distance from Putin, who is said to have a hard time finding his way around modern information technology.

Medvedev failed because of the system and because of himself: he was much more interested in the “restart” of Russian-American relations with Barack Obama, in a Russia integrated in Europe from “Lisbon to Vladivostok” and in a political thaw than Putin. In 2011, he ruthlessly put an end to his governor’s ambitions by announcing his return to the Kremlin and breaking off the Medvedev experiment, probably for fear of too much political openness.

During a visit to America in July 2010, Dmitry Medvedev is in Washington with then-US President Barack Obama.

laughing stock instead of statesman

“The successor” never managed to step out of the shadow of the overpowering sponsor; yea, in emulating him, he made himself ridiculous. In 2017, Alexei Navalny’s film about Medvedev’s life of luxury finally thwarted the image of the corruption fighter and made him a bogeyman in the eyes of the public. The drastic regression of freedom again under Putin from 2012 nevertheless revealed the contrast to Medvedev’s tenure.

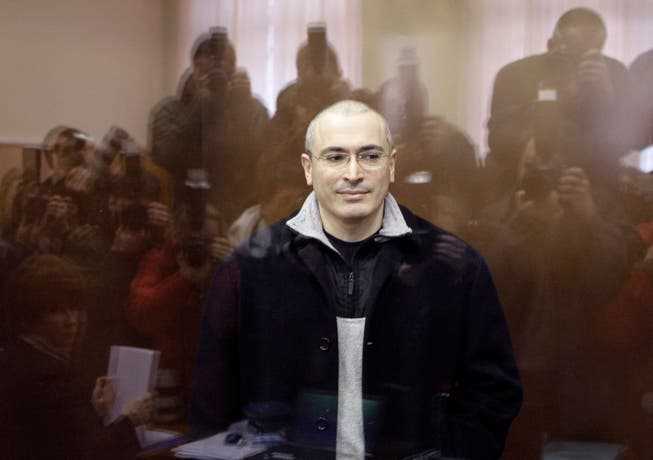

Russian satirist and journalist Viktor Shenderovich, a critic of the regime forced into exile, recently rememberedthat during Medvedev’s term of office, however, the second, highly questionable legal process against the magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who had fallen out of favor, and also the Georgian war of 2008 also took place – and that Russia’s liberal intelligentsia closed their eyes to it for too long because they did not live up to their illusions wanted to destroy.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky in court in Moscow in March 2009.

The question remains as to what extent Medvedev is using the moment to raise his profile out of calculation or whether he became a war propagandist out of conviction, loyalty or even on behalf of the Kremlin. Does he associate it with new political hopes? Is he again Putin’s safest value, with a view to the next presidential election in 2024? For political commentator Andrei Kolesnikov, only one thing is clear: Medvedev is thereby annulling all his previous successes. This is especially true for those who once placed the highest hopes in him. Even now he is more of a laughing stock than a statesman.

radicalization to nuclear war

The longer the “special operation” in Ukraine lasts and the more obvious it becomes that the intended “lightning war” has turned into an agonizing, costly battle, the more radical the rhetoric of the warmongers becomes. By arming Ukraine, the West is not only becoming a direct enemy, but is also forcing a real, brutal war on Russia instead of the “military operation”, they say. Their own hardship is explained by the fact that the Russian army is not fighting against weak Ukraine, but against powerful NATO.

The fact that this could lead straight to World War III and the use of nuclear weapons is now commonplace in state television discussion programs tinged with the harshest anti-Western rhetoric. The annihilation fantasies do not exclude their own country. All inhibitions seem to have fallen. Medvedev has not gone that far. But his rhetoric is also part of an increasingly insane hysteria and glorification of violence.