The federal administration denied a doctoral student access to explosive archive files. The historian goes all the way to federal court. And wins.

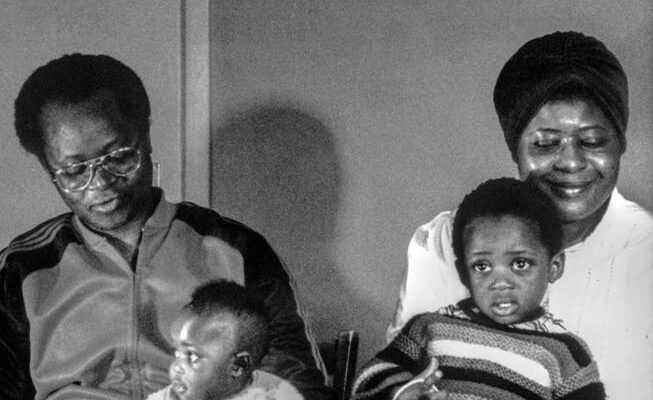

On January 11, 1988, the so-called Musey Affair broke out in the canton of Jura. The Jura police arrested Mathieu Musey and his family in the early hours of the morning on the orders of then Federal Councilor Elisabeth Kopp. At the time, Mathieu Musey, his wife and two small children were living illegally in Switzerland, in a small farmhouse in the municipality of Undervelier. The Musey family in 1987.

He is not a hero, says Jonathan Pärli. But he is brave. That is why the historian, who works at the University of Basel, received the “Award for Freedom of Research” from the Swiss Society for History (SGG). The SGG created the award specifically for Pärli. “He obtained a decision from the Federal Supreme Court that is epochal for contemporary history in this country,” says SGG President Sacha Zala.

Jonathan Pärli researches the history of asylum in Switzerland in the 20th century. The doctoral student is particularly interested in the case of Mathieu Musey, which made waves in the 1980s. When the philosopher, who was doing research at the Universities of Freiburg and Bern, was to be deported under Mobutu’s dictatorship (then the Republic of Zaire), churches, aid organizations and left-wing groups across the country showed solidarity with him. But in vain: in 1988, after 16 years, Musey and his family had to leave Switzerland. Why is still unclear to this day.

security of the country?

In 2017, Pärli came across an extensive dossier on Musey in the Swiss Federal Archives, which he absolutely wanted to consult. The documents are classified as “particularly sensitive personal data” and are therefore subject to a protection period of 50 years. At great expense in terms of time and money, Pärli succeeds in presenting a handwritten consent signed by Musey, according to which he agrees to the inspection of the files. Musey, who lives in Kinshasa, is interested in coming to terms with his story. Shortly before his deportation, he published the autobiographical book Asylum in Switzerland: Negroes must abstain or put democracy to the test.

However, the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), which is responsible for examining the request for access, is now demanding that Pärli submit a copy of a valid ID from Musey as well as the consent and copies of IDs of all family members mentioned in the files. «That was not possible. Musey did not have these papers and was also old and ill, »says Pärli. The SEM also brought the “public interest” into play, meaning that access to files endangered the security of the Confederation, among other things.

That doesn’t make sense to Pärli. In 2018 he lodged an appeal with the next higher instance, the Federal Administrative Court. It took the latter two years to inform him that Musey’s personality actually had to be protected and that the files were rightly blocked. Pärli then goes to the Federal Supreme Court, which now agrees: the Federal Administrative Court acted incorrectly and violated federal law, it restricts “freedom of science and research” and has to reassess the case. In addition, the SEM had to compensate the complainant for his expenses with 3000 francs. Pärli won, most likely he will be able to see the Musey dossier, but probably not before 2023 at the earliest – five years after his request for inspection. He has since submitted his doctoral thesis, although he had to forgo studying relevant sources. And Musey passed away in 2021.

Without the support of his father, the lawyer Kurt Pärli, as well as the lawyer Alexander Kley (both professors) and former friends of Musey, he would not have been able to pull this off, says the historian: “The first law firm I contacted made it clear to me that without a nothing goes with a war chest filled with 20,000 francs.” Pärli waved it off, and a lawyer friend of the parents stepped in.

The Pärli case shows that the regulation provided for in the national archive law in the event of a conflict, i.e. legal recourse, does not work. The historian would hardly have been able to successfully complete this without the free legal expertise from his private environment. In addition, the snail’s pace of the legal mill stands in the way of any academic career.

Pärli says the archive law needs to be revised in favor of research. The law strikes a balance between the interests of the private individuals mentioned in the sources, i.e. their protection of privacy, and the interest of the public in knowing about the present and the past. That can be a tightrope walk. In the case of Musey, it shouldn’t have been.

Rise of Privacy

Doctoral student Pärli is not an isolated case. Historians working on the recent past are increasingly coming across locked files. For example, Vincent Barras, medical historian at the University of Lausanne, and his team have repeatedly been prevented by archives and ethics committees from viewing the documents they need because they are subject to a protection period. For the same reason, employees of the military historian Michael Olsansky from ETH Zurich were “arbitrarily restricted” from accessing files of the General Staff, as he says: “The administration is making research more and more difficult.” Even scientists who deal with the topic of external placement are repeatedly faced with barriers.

One reason for this is the self-protection of the administration: they don’t want to be seen in the cards and don’t want to set a precedent. Linked to this is a second reason: the rise of data protection, which lawyers and ethicists are campaigning for. Initially directed against tech companies that collect digital personal data for commercial purposes, data protection has long since penetrated the health and archive sectors. It has almost gained the dignity of a human right without specifying what “sensitive data” is and whether and how data “belongs” to a human being.

In legal texts there is even talk of the “right to be forgotten”, the right to have your “own data” deleted. The EU Archives Commission recommends that archives strengthen data protection and no longer publish any documents or finding aids online that could endanger the “dignity of the data subjects”. That sounds well and good. It would probably be better to enable research that examines how human dignity has been violated in the past.