Georgia has become a hotbed of immigrants because of the war in Ukraine. Not only Ukrainians are drawn to Tbilisi, but also members of the opposition from Russia. As a permanent solution, however, Georgia is by no means suitable for everyone.

On the streets of Tbilisi, people speak more and more Russian in these weeks and months. This is not only because many Russian tourists vacation in the former Soviet republic known for beautiful landscapes and good food. Since the beginning of the war of aggression against Ukraine, there has also been an increasing number of opposition figures from Russia and Ukrainian refugees in the Georgian capital. According to official information, more than 26,000 refugees from Ukraine were registered in Georgia in August, while the number of Russian exiles is difficult to determine due to the visa-free regime.

The sympathies of the Europe-oriented Georgians in Tbilisi are clearly with the Ukraine: many shops express their solidarity with stickers and flags in blue and yellow, Ukrainian flags hang from the balconies. Slogans insulting the Russian head of state Putin can also be found in Tbilisi.

Escape only possible via Russia

Most of the Ukrainian refugees come from the newly occupied areas in the east and south of the country. Natalia Lukashova used to live in Nova Kakhovka in Kherson Oblast, a strategically important city on the Dnipro River. The 30-year-old primarily wanted to bring her daughter to safety. But the difficult economic situation was also a reason: “The money ran out, the shops closed,” she says.

Because the escape routes from the areas held by the occupiers only lead east or south and not across the front into the Ukrainian-controlled regions, the fugitives have no choice but to leave via Russia. Lukashowa first went to Crimea, which has been under Russian occupation since 2014, to her father, whom she had not seen for many years. But she didn’t last long there. “He didn’t believe what I said. He thinks we’re going to be freed,” says the Ukrainian. Finally she fled to Georgia via the North Caucasus.

The Lukashova couple fled from the Ukrainian province of Cherson to Georgia – the only way was through Russian territory.

Her husband Kirilo also arrived here later. He tells frightening stories about the conditions in the occupied province of Cherson. One of his friends was tortured. “They take the men out of the apartments.” From the balcony you can watch people being abducted on the open street. The humanitarian situation is desolate. Everywhere there are long queues in front of grocery stores or ATMs. Kirilo Lukashov estimates that 85 percent of the Chersonese population have fled. However, many also ended up in the dreaded Russian filtration camps, where the occupiers checked their victims for nationalist tattoos or their smartphones for suspicious messages.

Returning to Mariupol is not an option

Olga Rohowska’s flight also led from the Russian-occupied territory of Ukraine via southern Russia and the North Caucasus to Georgia. The journey, more than a thousand kilometers long, took seven days. “It was a spontaneous decision,” says the social worker, who comes from Mariupol, which was bombed by the Russian military. The air raids were the hardest to endure there, sometimes more than a hundred in one day. “I’m so happy to have come out.”

However, the war is also a burden for another reason: Many families with different political views have broken up in the meantime, says Rohowska. However, it is clear to her and her family that after the almost total destruction of Mariupol, they can never have a good attitude towards Russia. “We speak Russian, but we are pro-Ukrainian patriots.”

The social worker Olga Rohowska has absolutely no intention of returning to her hometown of Mariupol, not even after liberation. The largely destroyed place is associated with too much horror for them.

Together with other carers, Rohowska now looks after around fifty children of Ukrainian refugees on the upper floor of a kindergarten in Tbilisi. It is a project of the aid organization Save the Children. Her husband has meanwhile found work in a metal works nearby. “One hundred percent” they will return to Ukraine at some point, emphasizes Olga Rohowska. The only thing she can’t imagine is returning to Mariupol, even if that city were to be under Ukrainian control again. Too many people died there. “We’ve seen too much.”

Doubly discriminated against

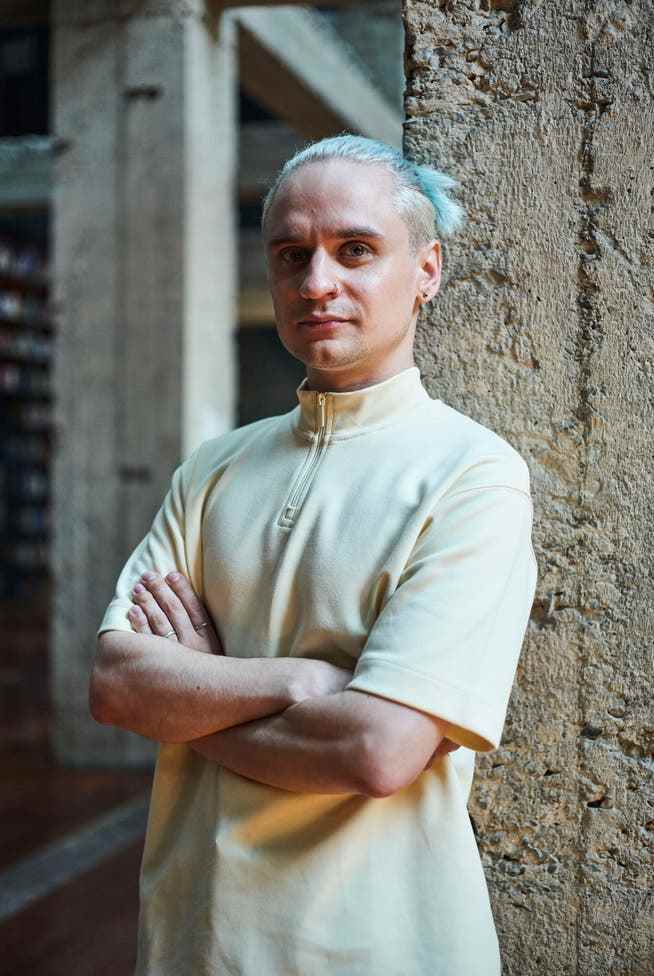

The 29-year-old journalist Anton Danilov has a completely different path behind him. The Russian, who grew up in Kaliningrad and most recently worked in Moscow, left his home country for Georgia in the spring. His mother had been pushing him to do it for a long time. The noose around Danilov had gotten too tight – on the one hand as a media representative for the magazine “Wonderzine”, who wrote about minorities and topics uncomfortable for the government, and on the other hand for him personally as a homosexual.

His choice of topic, for example the situation of homosexuals in the Russian army, was a thorn in the side of the authorities. This type of journalism was called “gay propaganda”. Roskomnadzor, the state media regulator, asked “Wonderzine” to remove two of his texts from the web – one about a person who was changing their gender identity.

The editors were given 24 hours to delete it. “In the end, we were blocked anyway,” explains Danilov. “We wanted to hire a lawyer, but our chances of winning were zero.” Now that he lives in Tbilisi – together with his friend who fled with him – he can at least write about any topic again. If he were to write about the massacre in Bucha in Russia, he would face years in prison.

The Russian Anton Danilow has turned his back on his home country. As a journalist and as a homosexual, he could not feel safe in Russia either professionally or privately.

The young man also felt the homophobic mood in society. In Moscow he was beaten in public. In Russia, people are pressured to hide their sexual identity. Since 2013, it has been banned in Russia to speak positively about homosexuality in the presence of minors or in the media. A legislative reform is currently being prepared in the Russian parliament that would make this ban much stricter.

But even in Tbilisi, Danilov is not safe from hostilities because of his homosexuality. He doesn’t dare wear his T-shirt with rainbow colors in this country. Although homosexual acts have been legal in Georgia since 2000, parts of society do not yet seem ready to accept this. More than once in Tbilisi there were actions by ultra-conservative Orthodox against the Gay Pride parade. In any case, Anton Danilow wants to move on from Georgia to Germany. He has already applied for asylum at the German embassy.

Came and stayed as a tourist

The Russian Vanya Shevchuk traveled to Georgia as a tourist for a few weeks in February – and decided to stay after the outbreak of war. The 21-year-old consultant for online education technologies comes from Khanty-Mansisk, a city around 2,600 kilometers east of Moscow. He has a more than remarkable family history in connection with the Russian-Ukrainian war: his great-great-grandfather was deported from the Ukraine to Siberia in the 1930s.

But the young Russian wasn’t stuck in Tbilisi because of his Ukrainian roots. His exile has other reasons. In the event of a general mobilization in Russia, Shevchuk feared that he would be drafted into the army. His political views also do not coincide with Putin’s course.

The opposition-minded Russian Vanya Shevchuk got stuck in Georgia as a tourist. He is waiting to see how the situation in Russia will develop.

Shevchuk is a sympathizer of the opposition Libertarian Party of Russia, which is being beset by the state’s repressive apparatus. “Many of my friends were arrested at demonstrations. I wouldn’t be safe either,” says Shevchuk. This feeling of insecurity manifested itself in him at the latest when Alexei Navalny was arrested last year. As a member of the opposition in Russia, you can now only communicate via encrypted channels, said the Siberian.

In conversations with his mother in Russia, a government employee, he tries not to broach the subject of the war in Ukraine too much. In the interview in Tbilisi, however, Shevchuk does not hold back his opinion: He accuses Putin of imperial ambitions and a conversion of Russia into a totalitarian system. “Since I was born, the opposition has become weaker and weaker,” he states. Vanya Shevchuk will remain in Georgia for the time being, he can stay here for 360 days without a visa and do his work online. However, since the sanctions against Russia began, he has had his wages paid out in cryptocurrency. He currently lives in a hostel. He says he met other Russians there. “But nobody who is for Putin.”

Collaboration: Tina Lagidze