Qatar, China, identity politics instead of implementing human rights: the traffic light government meanders between moral claims and moral-free decisions.

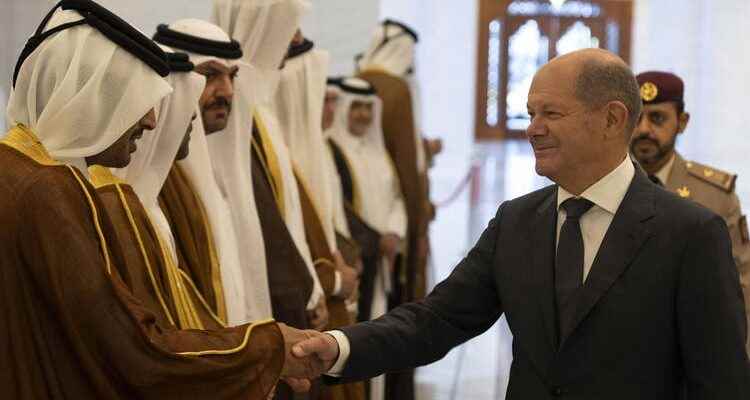

Islam is the basis of law and order in Qatar: Chancellor Scholz at a meeting with Qatar’s Emir in Doha last September.

In December 2021, the SPD, Greens and FDP in Germany signed a coalition agreement that promised to align politics in the future with the primacy of justice, freedom and sustainability. Now, almost a year later, the admonishingly raised German index finger has become an international laughingstock. Within society, civil liberties are eroding. And we are further away from sustainability than ever before.

The contrast between grandiose political propaganda and a realpolitik that retracts everything that has been said and turns it into the opposite is striking. Take the rhetoric, for example: in her first keynote speech in January 2022, Annalena Baerbock announced a feminist foreign policy; a month later, Chancellor Olaf Scholz spoke of a turning point. Both meant a priority orientation on human rights and especially on the rights of women, girls and queer people. Something similar was also defined as a domestic political goal.

What did actual political practice look like? Because of an imminent energy crisis after Putin’s attack on Ukraine, women’s and human rights receded noticeably into the background. Unforgotten is the iconic bow by Economics Minister Robert Habeck in the face of the Qatari Emir, with whom he wished to enter into an energy partnership to remedy the German emergency.

The relationship with Qatar

In Qatar, Islam is the basis of law and social order. Women are forced under the tutelage of their husbands or male relatives for life and deprived of all the liberties we take for granted. Homosexuality is illegal and carries draconian penalties. By using billions in oil and sending Islamist preachers, Qatar is also trying to support a misogynist Islam in Western countries. The country also funds the anti-Semitic Hamas. In fact, women domestic workers are enslaved and workers hired in South or Southeast Asia are treated inhumanely.

So far, no protest has been heard from the feminist-minded German foreign minister. She contented herself with the reminder that human rights should be respected.

Similar discrepancies between full-bodied speech and meek politics could also be observed in the case of the Chancellor, who set out for the Gulf in September 2022 to visit Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates – all countries where human rights are not particularly valued. Shortly before the trip, Scholz had eloquently invoked the human rights orientation of German foreign policy and the systemic struggle of democracies against autocracies in a speech to the United Nations.

The fact that such euphonious words by the Chancellor are obviously not always meant seriously became apparent in November, when Scholz, despite criticism, gave the go-ahead for the transfer of shares in the Port of Hamburg to the Chinese Cosco group. On the political stage, however, the talk dominates that one wants to reduce dependence on dictatorships and especially on China, with a particular focus on the critical infrastructure.

Human Rights and Islam

Domestic policy is no better: here there is a real opportunity to ensure the implementation of human rights. But while Federal Minister Nancy Faeser was pursuing symbolic politics in Qatar by wearing the “One Love” bandage, she remains silent on misogyny and queerism, anti-Semitism and racism in Muslim communities in Germany.

Islamism in Muslim organizations funded by Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Iran or the Erdogan government is not an issue for her ministry. Instead, the fight against Muslim hostility is proclaimed as an allegedly urgent social problem. Symptomatic of this attitude is that the group of experts on Islamism in the Federal Ministry of the Interior was immediately dissolved after the new management took office under Nancy Faeser, while the group on Islamophobia remained in place. Incidentally, any criticism of Islamist activities is considered hostility towards Muslims.

The goal of the colorful society

Booming silence generally prevails over misanthropy when the perpetrators have a migrant background. This applies to Islamist attacks as well as to sexual assaults and murders of girls, women, gays or trans people. The most recent brutal attack on two schoolgirls in Illerkirchberg only triggered stereotypical expressions of dismay and then disappeared from the media public. There was no political classification. On the contrary, many a person, such as the Green Prime Minister of Baden-Württemberg, warned against jumping to conclusions.

Apparently, one does not want to burden the goal of a new colorful society, which is implemented by promoting unregulated migration, with unsightly findings from German reality. It seems naïve when the government complains about discrimination against women in Afghanistan and recommends taking in more Afghan immigrants as a measure. These are already disproportionately involved in offenses against sexual self-determination.

Criticism is undesirable

All of this is banned from public discourse with the reference that naming the problems can benefit right-wing actors, stigmatize migrants, Muslims and other self-proclaimed victim groups, or promote misanthropy and racism in general. The interior minister sees the latter as the real problem.

Islamist extremism, left-wing extremism or foreign right-wing extremism, as represented by the Turkish ultra-nationalists of the “grey wolves”, play a subordinate role in the federal government. What is criticized abroad is given a folklore seal of approval at home. What’s more, an obscure concept of racism, which is based on the definition of identity-political activists, places the local population as a whole under general suspicion.

Criticism of social grievances is labeled as racist, Islamophobic or right-wing extremist and should be punished accordingly. This also applies to freedom of expression. Islamist agitation of the worst kind goes unchallenged on social networks, while criticism of migration policy or the government quickly leads to deletions.

Anyone who understands justice as identity politics and renounces the protection of human rights in migrant or Muslim communities is losing credibility. Foreign policy stagings by German politicians, which are not very convincing due to their rhetorical and pragmatic inconsistencies, seem even more dishonest under these circumstances.

Dependent instead of sustainable

Even the goal of sustainability set out in the coalition agreement remains a promise. The expansion of wind and solar energy is cementing dependence on China. The regime, widely considered to be a bigger problem than Russia, produces 80 percent of all solar panels, has minerals needed for the energy storage industry, and dominates battery cell manufacturing.

There are plans to cooperate with Qatar and the United Arab Emirates in the production of green hydrogen. A reduction in economic dependencies on autocratic regimes, which are verbosely ranted about at every suitable opportunity, would look different.

In order to bridge the time until the renewable energies are ready for the economy to build on, contracts for the supply of liquid gas have been signed with Qatar and the USA. The USA produces the gas on the basis of fracking, which is banned in Germany. The production and transport of liquid gas are extremely energy-intensive and harmful to the climate, but one hopes to pacify the green base, which rejects fracking in their own country just as strictly as climate-neutral nuclear power.

Between morality and realpolitik

In foreign policy, the federal government meanders between moral claims and moral-free, real-political decisions. Its scope for action is certainly limited by all sorts of adversities, but Germany’s international reputation would benefit from a little more straightforwardness in its political leadership.

Domestically, the government is hesitating because it does not want to admit that many of the groups with options for participation are like those who do not care about human rights abroad. The ideology of the Taliban is not only shared by men in Afghanistan, but also by many Afghan immigrants in Germany.

If the coalition agreement is not to become a waste of time, the double standards in domestic and foreign policy must be abandoned immediately.

Susanne Schroeter is a professor of ethnology at the Goethe University in Frankfurt and heads the Frankfurt Research Center for Global Islam. Most recently published by her: «Political Islam. Stress test for Germany», Gütersloher Verlagshaus (2019).